100 Essential Male Film Performances

Sort by:

Showing 1-50 of 99

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

Add items to section

Add items to section

Life Support

These are the supporting turns that are ineradicable. Without these scene-stealers holding it all together on the sidelines, the leads of their respective films would be totally lost.

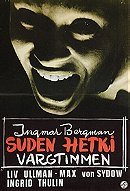

The Emigrants (1971)

Eddie Axberg

Troell’s epic, beautiful The Emigrants, based on Vilhelm Moberg’s classic novels, represents Scandinavian simplicity at its finest. Following a group of working class Swedes from the withering Smaland countryside to a supposed land of opportunity in turn-of-the-century Minnesota, the movie brutally recounts the hardships faced by immigrants in a way that is rarely captured on screen. Following his sister Kristina and her husband Karl-Oskar (Liv Ullmann and Max Von Sydow) to the States, Robert is a bit of a dreamer. He is too old to be living with his parents, and sees the treacherous ship ride across the Atlantic to be a rite of passage, a tool that will help him transition from a boy to a man who can support a family and take care of his sister as she has for him. He is an honest, non-flashy guy, one that is rarely seen anymore, actually: he values familial relationships, responsibility, staying together, being friends, and being helpful.

There is a genuine old-world charm to the actor’s sweet take on the character, and his purity and traditionalism never feel affected or false. Despite the film’s being nominated for several major Academy Awards (including Best Picture, Actress and Director), The Emigrants and it’s sequel, The New Land, are currently not available to DVD, and are even hard to find on VHS anymore (this classic cinema begs for the Criterion treatment—they had previously released the two films on Laserdisc). Troell’s films are intrinsic to understanding the experience of the Swedish immigrant, and Axberg’s performance is a rare glimpse into a type of character that we not only don’t see much anymore in modern film, but also into one that was infrequently there in the first place.

Troell’s epic, beautiful The Emigrants, based on Vilhelm Moberg’s classic novels, represents Scandinavian simplicity at its finest. Following a group of working class Swedes from the withering Smaland countryside to a supposed land of opportunity in turn-of-the-century Minnesota, the movie brutally recounts the hardships faced by immigrants in a way that is rarely captured on screen. Following his sister Kristina and her husband Karl-Oskar (Liv Ullmann and Max Von Sydow) to the States, Robert is a bit of a dreamer. He is too old to be living with his parents, and sees the treacherous ship ride across the Atlantic to be a rite of passage, a tool that will help him transition from a boy to a man who can support a family and take care of his sister as she has for him. He is an honest, non-flashy guy, one that is rarely seen anymore, actually: he values familial relationships, responsibility, staying together, being friends, and being helpful.

There is a genuine old-world charm to the actor’s sweet take on the character, and his purity and traditionalism never feel affected or false. Despite the film’s being nominated for several major Academy Awards (including Best Picture, Actress and Director), The Emigrants and it’s sequel, The New Land, are currently not available to DVD, and are even hard to find on VHS anymore (this classic cinema begs for the Criterion treatment—they had previously released the two films on Laserdisc). Troell’s films are intrinsic to understanding the experience of the Swedish immigrant, and Axberg’s performance is a rare glimpse into a type of character that we not only don’t see much anymore in modern film, but also into one that was infrequently there in the first place.

JxSxPx's rating:

The Damned (1969)

Helmut Berger

The performance of Helmut Berger in The Damned is frequently dismissed by cineasts as the overindulgence of his real-life lover, director Luchino Visconti. When your sugar daddy casts you in your first major film role as a cross-dressing, Nazi-collaborating pedophile who rapes his own mother (among other depravities), is he really being that generous? Perhaps, in a twisted and attention-getting manner.

Berger provides the most iconic image of Visconti’s long career with his entrance: dressed as Marlene Dietrich, he entertains his industrialist family at their estate as the Reichstag burns in Berlin (much to everyone’s shock and horror). If Berger did not follow these first moments of The Damned with a performance of some depth, however, it is doubtful his introductory Lola Lola would endure.

From The Blue Angel to the SS, Berger commits to his degenerate character without irony. That he can portray Martin as snippy, selfish and horribly immoral sans humor is but one strength of the performance within Visconti’s purposefully overwrought, grand soap opera. And Berger’s use of both feminine and masculine touchstones provides a complex look at gender identity, in an already-provocative film. If Visconti wishes to trace the downfall of a family from Weimer Republic into Nazi Germany, then Berger presents the perfect vessel in which to encapsulate this slide with his twisted, cranky Martin.

The performance of Helmut Berger in The Damned is frequently dismissed by cineasts as the overindulgence of his real-life lover, director Luchino Visconti. When your sugar daddy casts you in your first major film role as a cross-dressing, Nazi-collaborating pedophile who rapes his own mother (among other depravities), is he really being that generous? Perhaps, in a twisted and attention-getting manner.

Berger provides the most iconic image of Visconti’s long career with his entrance: dressed as Marlene Dietrich, he entertains his industrialist family at their estate as the Reichstag burns in Berlin (much to everyone’s shock and horror). If Berger did not follow these first moments of The Damned with a performance of some depth, however, it is doubtful his introductory Lola Lola would endure.

From The Blue Angel to the SS, Berger commits to his degenerate character without irony. That he can portray Martin as snippy, selfish and horribly immoral sans humor is but one strength of the performance within Visconti’s purposefully overwrought, grand soap opera. And Berger’s use of both feminine and masculine touchstones provides a complex look at gender identity, in an already-provocative film. If Visconti wishes to trace the downfall of a family from Weimer Republic into Nazi Germany, then Berger presents the perfect vessel in which to encapsulate this slide with his twisted, cranky Martin.

JxSxPx's rating:

Dogville (2003)

Paul Bettany

In von Trier’s Dogville, Bettany has an unenviable task, to play an “every man” who espouses morals and high-minded principals, but at the core is a sniveling, sheep-like coward. He gradually changes from a stumbling but right-headed, lovable town fixture (that you could just as easily see huggable Tom Hanks portraying) into the sort of cold, unfeeling monster that Rutger Hauer and Malcolm McDowell have made tidy livings from. And he does it without changing a thing about his character’s motivations or sense of self-righteousness, he does it naturally. Adrift on von Trier’s bare-bones sound stage, the actor does it without the benefits of sets, locations, or any props to speak of opposite a cast of heavies: legends Nicole Kidman, Lauren Bacall, Harriet Andersson, and Ben Gazzara are but a few of his co-stars. Clearly not a task for the faint of heart or for an amateur. Bettany delivers an assured performance, carefully modulating Tom’s descent from Thornton Wilderesque, plain-speaking authority to whimpering fool. It is a harrowing emotional journey that is as heartbreaking as it is reprehensible, in a movie that could easily devolve into a pedantic jeremiad against American society, but is instead stirring, deeply disturbing and provocative.

In von Trier’s Dogville, Bettany has an unenviable task, to play an “every man” who espouses morals and high-minded principals, but at the core is a sniveling, sheep-like coward. He gradually changes from a stumbling but right-headed, lovable town fixture (that you could just as easily see huggable Tom Hanks portraying) into the sort of cold, unfeeling monster that Rutger Hauer and Malcolm McDowell have made tidy livings from. And he does it without changing a thing about his character’s motivations or sense of self-righteousness, he does it naturally. Adrift on von Trier’s bare-bones sound stage, the actor does it without the benefits of sets, locations, or any props to speak of opposite a cast of heavies: legends Nicole Kidman, Lauren Bacall, Harriet Andersson, and Ben Gazzara are but a few of his co-stars. Clearly not a task for the faint of heart or for an amateur. Bettany delivers an assured performance, carefully modulating Tom’s descent from Thornton Wilderesque, plain-speaking authority to whimpering fool. It is a harrowing emotional journey that is as heartbreaking as it is reprehensible, in a movie that could easily devolve into a pedantic jeremiad against American society, but is instead stirring, deeply disturbing and provocative.

Ghost World (2001)

Steve Buscemi

Seymour is an obsessive collector out of touch with the modern world. When Buscemi’s Seymour utters the line “I can’t relate to 99% of humanity”, his role as the loveable loser type that he plays so well is instantly clear. He is defeated, resigned, and seething with bitterness, yet Buscemi plays him with a sincerity that makes the viewer wholly sympathetic and on his side. Seymour’s self-awareness mixed with a crippling fear/hatred of all those around him make him the ultimate Buscemi character role. Zwigoff’s Ghost World taps into the lives of people on the fringes of society. Their compulsions and affectations are at the root of who they are—when asked to list his top five interests, his first three are old-fashioned music genres (“traditional jazz, blues, and ragtime”)—and Seymour typifies a certain kind of outcast. It’s easy to imagine that in other hands this character could be reduced to a one-dimensional caricature, yet Buscemi makes him real. It’s in his small embarrassments and his small victories that Seymour becomes someone to root for. Buscemi brings it all to life and makes his biting sarcasm and misanthropic tendencies endearing with his understated charm.

Seymour is an obsessive collector out of touch with the modern world. When Buscemi’s Seymour utters the line “I can’t relate to 99% of humanity”, his role as the loveable loser type that he plays so well is instantly clear. He is defeated, resigned, and seething with bitterness, yet Buscemi plays him with a sincerity that makes the viewer wholly sympathetic and on his side. Seymour’s self-awareness mixed with a crippling fear/hatred of all those around him make him the ultimate Buscemi character role. Zwigoff’s Ghost World taps into the lives of people on the fringes of society. Their compulsions and affectations are at the root of who they are—when asked to list his top five interests, his first three are old-fashioned music genres (“traditional jazz, blues, and ragtime”)—and Seymour typifies a certain kind of outcast. It’s easy to imagine that in other hands this character could be reduced to a one-dimensional caricature, yet Buscemi makes him real. It’s in his small embarrassments and his small victories that Seymour becomes someone to root for. Buscemi brings it all to life and makes his biting sarcasm and misanthropic tendencies endearing with his understated charm.

JxSxPx's rating:

The Godfather: Part II (1974)

John Cazale

Poor Fredo. The fragile brother. The shy, sad little boy in the shadow of his brasher, bolder brothers Sonny and Michael, stuck in the middle and given less to do than adopted sibling Tom Hagen. As the broken center of the Corleone family, he’s the classic tragic hero without a lick of courage in his cowering frame—and as essayed with grace and grand humility by Cazale, Fredo is also the final nail in the mafia clan’s coffin. You can see the defeat registered across this often unsung ‘70s icon’s angular face, a look that says he never fit in, not even when he tried. In loyalty, he earned ridicule, not respect. In betrayal, he earned the classic kiss off of death. While his time on the planet was far too short, Cazale manufactured his continuing cinematic legacy with this unusual and unforgettable role. Dying of cancer in the late ‘70s after a blazing character actor career, Cazale almost seemed destined to be Fredo in real life as well—a wannabe star that had to settle for an afterlife as movie myth. It seems only fitting.

Poor Fredo. The fragile brother. The shy, sad little boy in the shadow of his brasher, bolder brothers Sonny and Michael, stuck in the middle and given less to do than adopted sibling Tom Hagen. As the broken center of the Corleone family, he’s the classic tragic hero without a lick of courage in his cowering frame—and as essayed with grace and grand humility by Cazale, Fredo is also the final nail in the mafia clan’s coffin. You can see the defeat registered across this often unsung ‘70s icon’s angular face, a look that says he never fit in, not even when he tried. In loyalty, he earned ridicule, not respect. In betrayal, he earned the classic kiss off of death. While his time on the planet was far too short, Cazale manufactured his continuing cinematic legacy with this unusual and unforgettable role. Dying of cancer in the late ‘70s after a blazing character actor career, Cazale almost seemed destined to be Fredo in real life as well—a wannabe star that had to settle for an afterlife as movie myth. It seems only fitting.

JxSxPx's rating:

Benicio del Toro

Benecio Del Toro is one of those actors that can wear gravitas as a cloak, manipulating its power for his own secret purposes. As the audience, we aren’t stifled by this but rather mesmerized by it in quite the same way as we were in his Oscar winning performance in Stephen Soderbergh’s layered Traffic. Inarritu’s 21 Grams utilizes a jagged rather than linear story structure, where we are fed the parts of the story gradually. When pieced together, these fragmented shards form the following narrative: Paul Rivers (Sean Penn) is a dying mathematician who received a heart from recovering drug addict Christina Peck’s (Naomi Watts) husband, who was inexplicably killed in a hit run.

Where Del Toro fits in to the story, as reborn Christian and former criminal Jack Jordan is in his rather shocking role of responsibility in the crash that killed Christina’s husband. Del Toro’s Jack moves through the film as if underwater, sometimes sluggish, sometimes weary but always searching, trying desperately to do the right thing. His tirelessly devoted wife Marianne (Melissa Leo) is his biggest advocate helping him and convincing him for a short while to forget the accident took place, to hide it, to cover it up, for their family. As the tormented Jack, wrestling with the misdeeds of his past and present amidst a volatile relationship with God, Del Toro’s impressive, inspiring work garnered him an Academy Award nomination and much-deserved critical accolades; a fabulous performance among a growing body of distinguished work that seems to get stronger and stronger with age.

Benecio Del Toro is one of those actors that can wear gravitas as a cloak, manipulating its power for his own secret purposes. As the audience, we aren’t stifled by this but rather mesmerized by it in quite the same way as we were in his Oscar winning performance in Stephen Soderbergh’s layered Traffic. Inarritu’s 21 Grams utilizes a jagged rather than linear story structure, where we are fed the parts of the story gradually. When pieced together, these fragmented shards form the following narrative: Paul Rivers (Sean Penn) is a dying mathematician who received a heart from recovering drug addict Christina Peck’s (Naomi Watts) husband, who was inexplicably killed in a hit run.

Where Del Toro fits in to the story, as reborn Christian and former criminal Jack Jordan is in his rather shocking role of responsibility in the crash that killed Christina’s husband. Del Toro’s Jack moves through the film as if underwater, sometimes sluggish, sometimes weary but always searching, trying desperately to do the right thing. His tirelessly devoted wife Marianne (Melissa Leo) is his biggest advocate helping him and convincing him for a short while to forget the accident took place, to hide it, to cover it up, for their family. As the tormented Jack, wrestling with the misdeeds of his past and present amidst a volatile relationship with God, Del Toro’s impressive, inspiring work garnered him an Academy Award nomination and much-deserved critical accolades; a fabulous performance among a growing body of distinguished work that seems to get stronger and stronger with age.

JxSxPx's rating:

Ninotchka (1939)

Melvyn Douglas

In the years before World War II, wedged between the Busby Berkeley musicals and the Marx Brothers romps, there were the quick-witted comedies like The Philadelphia Story with James Stewart, Cary Grant and Kate Hepburn, and The Thin Man with Myrna Loy and William Powell. One of the last and most loved of that period was 1939’s Ninotchka starring Greta Garbo as the by-the-book Bolshevik from Russia who arrives in Paris to negotiate possession of an exiled grand duchess’ jewels. Douglas, playing the duchess’ representative, falls for the staid Ninotchka. “Must you flirt?” she asks dryly. “Well, I don’t have to but I find it natural,” he replies. “Suppress it,” she acidly returns. And so it continues, as Garbo sets ‘em up and Melvyn Douglas knocks ‘em down, line by clever line. Douglas never misses a beat with timing no doubt honed during several years of stage work prior to his long, illustrious film career. In addition to a Tony award and an Emmy, Douglas went on to win two Oscars: one for the Paul Newman classic Hud, and the last for his supporting role in Hal Ashby’s Being There. Still, it would be his stalwart wooing of Garbo in a classic film that would delight audiences around the world, on the eve of a tragic war.

In the years before World War II, wedged between the Busby Berkeley musicals and the Marx Brothers romps, there were the quick-witted comedies like The Philadelphia Story with James Stewart, Cary Grant and Kate Hepburn, and The Thin Man with Myrna Loy and William Powell. One of the last and most loved of that period was 1939’s Ninotchka starring Greta Garbo as the by-the-book Bolshevik from Russia who arrives in Paris to negotiate possession of an exiled grand duchess’ jewels. Douglas, playing the duchess’ representative, falls for the staid Ninotchka. “Must you flirt?” she asks dryly. “Well, I don’t have to but I find it natural,” he replies. “Suppress it,” she acidly returns. And so it continues, as Garbo sets ‘em up and Melvyn Douglas knocks ‘em down, line by clever line. Douglas never misses a beat with timing no doubt honed during several years of stage work prior to his long, illustrious film career. In addition to a Tony award and an Emmy, Douglas went on to win two Oscars: one for the Paul Newman classic Hud, and the last for his supporting role in Hal Ashby’s Being There. Still, it would be his stalwart wooing of Garbo in a classic film that would delight audiences around the world, on the eve of a tragic war.

JxSxPx's rating:

Jackie Brown (1997)

Robert Forster

For all of the praise lavished upon Tarantino for his directing, writing and encyclopedic knowledge of all things cinema, perhaps not enough is made of his absolutely note-perfect casting. Aside from Woody Allen, no other modern American filmmaker continually displays such a knack for finding the ideal actor for any given character part, for elevating an underrated or no-longer-fashionable performer out of the ghetto of indistinct appearances in indistinct films to a role that feels tailor made for their neglected talents. Forster, veteran of seemingly countless action flicks and cop shows throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, is not the star of Jackie Brown (that would be Pam Grier, getting a Tarantino-style career revival of her own), but he is very much its quiet emotional center. As the weary bail bondsman Max Cherry, Forster’s genial schoolboy crush on Grier’s titular heroine turns a twisty caper into an unexpectedly sweet meditation on aging and the possibility of romance in the face of diminished expectations. A knowing riff on Forster’s everyman anonymity (he’s one of those actors that you know you’ve seen before, but can never quite identify), Tarantino has Forster naturally inhabit Max in a way that a more widely recognizable “star” could never have been able to, creating one the most emotionally resonant characters in the entire Tarantino canon in the process.

For all of the praise lavished upon Tarantino for his directing, writing and encyclopedic knowledge of all things cinema, perhaps not enough is made of his absolutely note-perfect casting. Aside from Woody Allen, no other modern American filmmaker continually displays such a knack for finding the ideal actor for any given character part, for elevating an underrated or no-longer-fashionable performer out of the ghetto of indistinct appearances in indistinct films to a role that feels tailor made for their neglected talents. Forster, veteran of seemingly countless action flicks and cop shows throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s, is not the star of Jackie Brown (that would be Pam Grier, getting a Tarantino-style career revival of her own), but he is very much its quiet emotional center. As the weary bail bondsman Max Cherry, Forster’s genial schoolboy crush on Grier’s titular heroine turns a twisty caper into an unexpectedly sweet meditation on aging and the possibility of romance in the face of diminished expectations. A knowing riff on Forster’s everyman anonymity (he’s one of those actors that you know you’ve seen before, but can never quite identify), Tarantino has Forster naturally inhabit Max in a way that a more widely recognizable “star” could never have been able to, creating one the most emotionally resonant characters in the entire Tarantino canon in the process.

JxSxPx's rating:

Ed Harris

Harris’s performance as John Glenn in The Right Stuff is one of the finest supporting turns of the ‘80s. Harris has always been an interesting and dynamic character actor, and in the mold Christopher Walken, Michael Caine or his Stuff co-star Sam Shepard, Harris has the unique ability to turn out a strong performance in even the most baneful or overloaded of films. But when Harris has a part in a strong, meaty film like Kaufman’s, he simply shines. Harris is John Glenn, the first man to orbit the Earth, with a gleam of pride and glory in his laser-blue eyes. Harris’s Glenn is the ultimate Boy Scout, a true believer in the space program, a proper all-American who believes in what he’s doing without the slightest reservation. He immerses himself in the role, employing the firm, open grin of a superstar and the wide, believing, eager eyes of an innocent. It is a magnificent paradox. One would have expected Harris to play Glenn against the man’s legend, to deconstruct him or attempt to reveal his dark side.

Instead, Harris plays Glenn in strict accordance with the man’s public legend as a true believing patriot. In one of the film’s best scenes, Glenn berates his fellow astronauts for their wanton carousing and womanizing. In the hands of a less capable actor, this scene would have served to align us against Glenn, to position him as a sort of authority for us to distrust and renounce. But by playing Glenn as a super patriotic believer in the space program, Harris makes even the most disenchanted and cynical viewers believe in the righteousness of the American space program and long for its return to glory.

Harris’s performance as John Glenn in The Right Stuff is one of the finest supporting turns of the ‘80s. Harris has always been an interesting and dynamic character actor, and in the mold Christopher Walken, Michael Caine or his Stuff co-star Sam Shepard, Harris has the unique ability to turn out a strong performance in even the most baneful or overloaded of films. But when Harris has a part in a strong, meaty film like Kaufman’s, he simply shines. Harris is John Glenn, the first man to orbit the Earth, with a gleam of pride and glory in his laser-blue eyes. Harris’s Glenn is the ultimate Boy Scout, a true believer in the space program, a proper all-American who believes in what he’s doing without the slightest reservation. He immerses himself in the role, employing the firm, open grin of a superstar and the wide, believing, eager eyes of an innocent. It is a magnificent paradox. One would have expected Harris to play Glenn against the man’s legend, to deconstruct him or attempt to reveal his dark side.

Instead, Harris plays Glenn in strict accordance with the man’s public legend as a true believing patriot. In one of the film’s best scenes, Glenn berates his fellow astronauts for their wanton carousing and womanizing. In the hands of a less capable actor, this scene would have served to align us against Glenn, to position him as a sort of authority for us to distrust and renounce. But by playing Glenn as a super patriotic believer in the space program, Harris makes even the most disenchanted and cynical viewers believe in the righteousness of the American space program and long for its return to glory.

JxSxPx's rating:

Milk (2008)

Emile Hirsch

Milk did what many previous films have failed to do: he took a real-life person and was able to present an authentic take on his spirit and that of the people around him without having to resort to cliché or stock storytelling techniques. While Sean Penn has deservedly gotten the most praise for his role as the titular Harvey Milk, it was Emile Hirsch’s Cleve Jones that flew in the face of cinematic convention, as far as “gay” characters go. Cleve is a hero to a movement, but Hirsch and Van Sant keenly also shed light on the many facets of his personality: he can be swishy, sexual, funny, fierce and strong. Our introduction to Cleve reveals a young, cocky, and amusing transplant to the San Francisco area. His very energy and his vibrancy make a bracing impression on Milk, and their friendship evolves into an intimate, intellectual relationship that has its eye set on the future of the gay rights movement. Hirsch imbues Cleve with pure effervescence, and a scrappy optimism that makes him seem unstoppable. One of the more moving moments in the entire film centers on Cleve’s mobilization of the larger San Francisco community in reaction to Harvey’s assassination. He is fueled by anger and sadness, but also by the need to celebrate Harvey’s life. Hirsch’s ease in making the audience feel some measure of his feeling without any cheap, sentimental tricks stands as one of the most affecting moments in recent film history, and one of the finest heterosexual interpretations of homosexuality.

Milk did what many previous films have failed to do: he took a real-life person and was able to present an authentic take on his spirit and that of the people around him without having to resort to cliché or stock storytelling techniques. While Sean Penn has deservedly gotten the most praise for his role as the titular Harvey Milk, it was Emile Hirsch’s Cleve Jones that flew in the face of cinematic convention, as far as “gay” characters go. Cleve is a hero to a movement, but Hirsch and Van Sant keenly also shed light on the many facets of his personality: he can be swishy, sexual, funny, fierce and strong. Our introduction to Cleve reveals a young, cocky, and amusing transplant to the San Francisco area. His very energy and his vibrancy make a bracing impression on Milk, and their friendship evolves into an intimate, intellectual relationship that has its eye set on the future of the gay rights movement. Hirsch imbues Cleve with pure effervescence, and a scrappy optimism that makes him seem unstoppable. One of the more moving moments in the entire film centers on Cleve’s mobilization of the larger San Francisco community in reaction to Harvey’s assassination. He is fueled by anger and sadness, but also by the need to celebrate Harvey’s life. Hirsch’s ease in making the audience feel some measure of his feeling without any cheap, sentimental tricks stands as one of the most affecting moments in recent film history, and one of the finest heterosexual interpretations of homosexuality.

JxSxPx's rating:

Harvey Keitel

How does an actor known for playing mob operatives and punks depict the man who betrays Jesus Christ? By making Judas a goodfella. And it works. When we first meet Judas, threatening Jesus and jumping Romans in the street, Keitel portrays him with a little of the pimp he plays in Taxi Driver. After becoming a convert, Judas promises Jesus: “But if you stray this much from the path, I’ll kill you”. Keitel, swaggering a bit in his robe and sandals, holds up his hand and pinches his thumb and forefinger together for emphasis. His Judas is always grounded in the literal. Once Jesus has won Judas’s trust, Keitel plays the right-hand man as the loyal, but slightly dim capo: “Every day you have a different plan”, he half whines in frustration when Jesus tells him he must be crucified. Keitel’s worldly, prosaic, yet doggedly loyal Judas is the perfect foil for Willem Dafoe’s philosophical, naïve Jesus, whose miracles and parables Judas is often at a loss to understand.

While Scorsese can’t help the occasional scene set up as a tableau from Renaissance depictions of the passion, naturalistic acting carries the film, with Biblical speech converted to modern vernacular. In one of the film’s key scenes, when Judas agrees to betray Jesus to the Romans, Keitel works in complete concert with the camera. In a close-up with Dafoe, Judas in the foreground begins the scene slightly out of focus, fighting back tears. He exhales, his face relaxes, and he composes himself as the camera brings him into focus with Jesus. It’s a literal and figurative moment of clarity, and no scene in the film better captures Temptation‘s goal of stressing the human side of the epic events of the passion.

How does an actor known for playing mob operatives and punks depict the man who betrays Jesus Christ? By making Judas a goodfella. And it works. When we first meet Judas, threatening Jesus and jumping Romans in the street, Keitel portrays him with a little of the pimp he plays in Taxi Driver. After becoming a convert, Judas promises Jesus: “But if you stray this much from the path, I’ll kill you”. Keitel, swaggering a bit in his robe and sandals, holds up his hand and pinches his thumb and forefinger together for emphasis. His Judas is always grounded in the literal. Once Jesus has won Judas’s trust, Keitel plays the right-hand man as the loyal, but slightly dim capo: “Every day you have a different plan”, he half whines in frustration when Jesus tells him he must be crucified. Keitel’s worldly, prosaic, yet doggedly loyal Judas is the perfect foil for Willem Dafoe’s philosophical, naïve Jesus, whose miracles and parables Judas is often at a loss to understand.

While Scorsese can’t help the occasional scene set up as a tableau from Renaissance depictions of the passion, naturalistic acting carries the film, with Biblical speech converted to modern vernacular. In one of the film’s key scenes, when Judas agrees to betray Jesus to the Romans, Keitel works in complete concert with the camera. In a close-up with Dafoe, Judas in the foreground begins the scene slightly out of focus, fighting back tears. He exhales, his face relaxes, and he composes himself as the camera brings him into focus with Jesus. It’s a literal and figurative moment of clarity, and no scene in the film better captures Temptation‘s goal of stressing the human side of the epic events of the passion.

JxSxPx's rating:

Alfred Molina

This biopic of writer Joe Orton earns miles from Gary Oldman’s natural performance as the fallen playwright. The young Orton had hardly a literary inclination until meeting Alfred Molina’s Ken, a lit junkie with a pile of rejected novels, when at acting school. At first the two wrote as a team, and then Joe began casually scripting edgy crowd-pleasers for the stage. Thus, Ken’s tutelage of Joe skyrockets beyond its mentor, while Ken’s mentorship to Joe (of another kind) doesn’t fly so well.

The two gay men converge like magnets, with Ken as the putative personal assistant to Joe, who desires “playtime” outside the relationship. He takes to cruising for men with ease, while Ken awkwardly tries to keep up. The homo-repressed 1960s Britain makes the film an early, doomed entry in queer cinema—about which we shouldn’t gripe since it is better than no queer cine at all. In this form, Ken embodies the obsessive half, whose purpose hardly extends beyond supporting his mate’s profession. Next to the happening Joe, Molina’s Ken—bald by his late 20s—is a nervy schlub: think the late Telly Savalas doing J. Alfred Prufrock. Molina stares down all clichés, veering away from effeminate tones when they would be most convenient and avoids trapping Ken into a brooding madman, and more than holds his own next to an astonishing Oldman. His “suffering wife” or “other half” is far more humorous than bitchy: he shuffles like a biddy when feeling slighted though bellows with Orton at the good times. Regretfully, Ken’s sickness was real, and he had to down pills every day to stay even. It is this combination of mental illness and self-diagnoses that leads, in part, to the end both of their lives, at Ken’s frenzied hands.

This biopic of writer Joe Orton earns miles from Gary Oldman’s natural performance as the fallen playwright. The young Orton had hardly a literary inclination until meeting Alfred Molina’s Ken, a lit junkie with a pile of rejected novels, when at acting school. At first the two wrote as a team, and then Joe began casually scripting edgy crowd-pleasers for the stage. Thus, Ken’s tutelage of Joe skyrockets beyond its mentor, while Ken’s mentorship to Joe (of another kind) doesn’t fly so well.

The two gay men converge like magnets, with Ken as the putative personal assistant to Joe, who desires “playtime” outside the relationship. He takes to cruising for men with ease, while Ken awkwardly tries to keep up. The homo-repressed 1960s Britain makes the film an early, doomed entry in queer cinema—about which we shouldn’t gripe since it is better than no queer cine at all. In this form, Ken embodies the obsessive half, whose purpose hardly extends beyond supporting his mate’s profession. Next to the happening Joe, Molina’s Ken—bald by his late 20s—is a nervy schlub: think the late Telly Savalas doing J. Alfred Prufrock. Molina stares down all clichés, veering away from effeminate tones when they would be most convenient and avoids trapping Ken into a brooding madman, and more than holds his own next to an astonishing Oldman. His “suffering wife” or “other half” is far more humorous than bitchy: he shuffles like a biddy when feeling slighted though bellows with Orton at the good times. Regretfully, Ken’s sickness was real, and he had to down pills every day to stay even. It is this combination of mental illness and self-diagnoses that leads, in part, to the end both of their lives, at Ken’s frenzied hands.

Rushmore (1998)

Bill Murray

Where did Bill Murray have to go to find his Herman Blume? A rich industrialist, with a wife who despises him and sons who horrify him, he’s desperately in need of a friend. That he looks to Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), a high school student who manages to overachieve and underachieve simultaneously, for cues on how to live speaks volumes. They’re both too smart and too self-assured for their own good; it only seems to alienate them and Murray’s tiny winces clue us in to Blume’s sagging unhappiness. Is there a funnier expression of late middle-age discontentment than Murray climbing a high dive in front of his party guests, with a drink and a cigarette, cannon-balling into the pool and sinking himself to the bottom, pausing to swallow a silent, underwater scream? But around Max, Blume beams. Murray makes his glee so contagious that at times it has the ability to pull you up out of your seat. Rushmore re-introduced Murray to an audience that had largely begun to forget about him. And while he has had memorable roles before and since, Anderson’s Rushmore may be the first time that every aspect of a production was on his elevated level. He seems to almost have a direct line of communication with the camera, so that he makes the distance between the viewer and the screen almost disappear.

Where did Bill Murray have to go to find his Herman Blume? A rich industrialist, with a wife who despises him and sons who horrify him, he’s desperately in need of a friend. That he looks to Max Fischer (Jason Schwartzman), a high school student who manages to overachieve and underachieve simultaneously, for cues on how to live speaks volumes. They’re both too smart and too self-assured for their own good; it only seems to alienate them and Murray’s tiny winces clue us in to Blume’s sagging unhappiness. Is there a funnier expression of late middle-age discontentment than Murray climbing a high dive in front of his party guests, with a drink and a cigarette, cannon-balling into the pool and sinking himself to the bottom, pausing to swallow a silent, underwater scream? But around Max, Blume beams. Murray makes his glee so contagious that at times it has the ability to pull you up out of your seat. Rushmore re-introduced Murray to an audience that had largely begun to forget about him. And while he has had memorable roles before and since, Anderson’s Rushmore may be the first time that every aspect of a production was on his elevated level. He seems to almost have a direct line of communication with the camera, so that he makes the distance between the viewer and the screen almost disappear.

JxSxPx's rating:

Nick Nolte

Nick Nolte has so little screen time in Olivier Assayas’s Clean (2004) that it could be relatively easy to overlook his subtle contribution to the film. There is no question that Maggie Cheung stole the show—a performance that won her a Best Actress Award at Cannes—but Nolte’s performance as the aging, forgiving patriarch, Albrecht Hauser is so smolderingly brilliant that he deserves at least as much praise as Cheung received to be sent his way. Nolte is part of that small coterie of actors - Tom Sizemore, Gary Busey, Mickey Rourke, etc.—who, despite their off-screen problems, can absolutely shine when given the right role and directorial support. With that said, our first glimpse of Albrecht isn’t pretty—he looks like Jeff Bridge’s “Dude” from The Big Lebowski on a bad day and sounds like Tom Waits with a hangover. But, this initial observation gives way to a genuine feeling of astonishment as Nolte fills the role of a man who must keep everyone happy, despite filial tensions. These include his ailing wife who blames her daughter-in-law Emily (Cheung) for her son’s accidental overdose; his grandson Jay who doesn’t understand why his father died or why his mother abandoned him; and Emily herself, who is overcome with guilt about the blame she has been levied with for her husband’s death, her son’s predicament and basically everyone else’s problems. Yet, with all of these intricate family dynamics, Albrecht tries to hold it all together by being warm, accommodating and almost Panglossian. Let’s take a minute to process that - since when does one associate Nick Nolte with being “warm” or “accommodating”? But, that is probably the best reason why his performance has made it to the PopMatters list - a strong, under-appreciated supporting role in an independent film that no one expected, least of all probably Nolte himself.

Nick Nolte has so little screen time in Olivier Assayas’s Clean (2004) that it could be relatively easy to overlook his subtle contribution to the film. There is no question that Maggie Cheung stole the show—a performance that won her a Best Actress Award at Cannes—but Nolte’s performance as the aging, forgiving patriarch, Albrecht Hauser is so smolderingly brilliant that he deserves at least as much praise as Cheung received to be sent his way. Nolte is part of that small coterie of actors - Tom Sizemore, Gary Busey, Mickey Rourke, etc.—who, despite their off-screen problems, can absolutely shine when given the right role and directorial support. With that said, our first glimpse of Albrecht isn’t pretty—he looks like Jeff Bridge’s “Dude” from The Big Lebowski on a bad day and sounds like Tom Waits with a hangover. But, this initial observation gives way to a genuine feeling of astonishment as Nolte fills the role of a man who must keep everyone happy, despite filial tensions. These include his ailing wife who blames her daughter-in-law Emily (Cheung) for her son’s accidental overdose; his grandson Jay who doesn’t understand why his father died or why his mother abandoned him; and Emily herself, who is overcome with guilt about the blame she has been levied with for her husband’s death, her son’s predicament and basically everyone else’s problems. Yet, with all of these intricate family dynamics, Albrecht tries to hold it all together by being warm, accommodating and almost Panglossian. Let’s take a minute to process that - since when does one associate Nick Nolte with being “warm” or “accommodating”? But, that is probably the best reason why his performance has made it to the PopMatters list - a strong, under-appreciated supporting role in an independent film that no one expected, least of all probably Nolte himself.

Joe Pesci

In one of cinema’s most candid, ruthless wise guy roles, Pesci gives the performance of his career as Tommy DeVito, a ruthless gangster with a comic’s discourse. The hierarchy and sociology of the crime syndicate plays out like some sort of Shakespearean kingdom, with Tommy as one of the most brutal foot soldiers. Though known for his classic club scene with Ray Liotta (“What do you mean funny? Funny how? I amuse you?”) I was always partial to the scene where his character’s mom (played by Scorsese’s real-life mother Catherine) catches the tough guys (Pesci, Liotta and Robert DeNiro) sneaking through her house. They stumble in late one night, after having committed the ultimate wise guy sin of killing a “made” man, the body still fresh in the trunk of their car. While eating Pesci explains the blood on his shirt by saying they hit a deer, and he needs to borrow her big knife. “The hoof got caught in the grill and I gotta hack it off.” The kitchen talk affords Pesci the opportunity to effectively showcase his acting chops, going from psychopath to mama’s boy in a matter of seconds. Ironically, he played almost the same character, but with more slapstick, the very same year in the kid friendly Macauley Culkin vehicle Home Alone, which was a huge box office success. Coupled with his nuanced turn in Scorsese’s critical blockbuster, Pesci proved himself to be a consummate supporting actor, taking home the Oscar for his work as Tommy ten years after his first nomination, for another Scorsese work, Raging Bull. Pesci has had a career of curious ups and downs, in both drama and comedy, but he has never chosen the easy path, as witnessed by his full immersion into Tommy’s rage and lack of intelligence - this lack of vanity only bolsters the actor’s range and commitment to excellence.

In one of cinema’s most candid, ruthless wise guy roles, Pesci gives the performance of his career as Tommy DeVito, a ruthless gangster with a comic’s discourse. The hierarchy and sociology of the crime syndicate plays out like some sort of Shakespearean kingdom, with Tommy as one of the most brutal foot soldiers. Though known for his classic club scene with Ray Liotta (“What do you mean funny? Funny how? I amuse you?”) I was always partial to the scene where his character’s mom (played by Scorsese’s real-life mother Catherine) catches the tough guys (Pesci, Liotta and Robert DeNiro) sneaking through her house. They stumble in late one night, after having committed the ultimate wise guy sin of killing a “made” man, the body still fresh in the trunk of their car. While eating Pesci explains the blood on his shirt by saying they hit a deer, and he needs to borrow her big knife. “The hoof got caught in the grill and I gotta hack it off.” The kitchen talk affords Pesci the opportunity to effectively showcase his acting chops, going from psychopath to mama’s boy in a matter of seconds. Ironically, he played almost the same character, but with more slapstick, the very same year in the kid friendly Macauley Culkin vehicle Home Alone, which was a huge box office success. Coupled with his nuanced turn in Scorsese’s critical blockbuster, Pesci proved himself to be a consummate supporting actor, taking home the Oscar for his work as Tommy ten years after his first nomination, for another Scorsese work, Raging Bull. Pesci has had a career of curious ups and downs, in both drama and comedy, but he has never chosen the easy path, as witnessed by his full immersion into Tommy’s rage and lack of intelligence - this lack of vanity only bolsters the actor’s range and commitment to excellence.

JxSxPx's rating:

Dennis Quaid

With Julianne Moore’s stunning performance taking center stage, it was easy to overlook the sterling work of the supporting actors in Haynes’s sublime evocation of 50s film melodrama. But the entire cast of this amazing film (from Patricia Clarkson as the nosy best friend to Viola Davis as the maid) bravely transcended parody and succeeded in imbuing melodramatic archetypes with their own distinctive, modern presence. Perhaps most extraordinary of all was Quaid’s performance as Frank, the not-so-straight-laced husband whose belated emergence from the closet sets the drama in motion. The question of how to pitch a performance in a film that is at least part homage is a tricky one, but Quaid triumphed by delivering a performance of utter sincerity and truthfulness. Frank is not, by any means, a particularly sympathetic character, but the brilliance of Quaid’s interpretation was to illustrate the extent to which Frank’s cruelty and hypocrisy stem from repression, fear and deep self-loathing. By so doing, he uncovered a core of vulnerability in the character that never descended to the level of sentimentality. In one particularly savage scene Quaid even manages to restore shock value to the now-over-used “F”-word (watch for Moore’s shocked reaction). And the pivotal late sequence in which he confesses to Moore’s Cathy that he’s “fallen in love” is a heart-breaker for a litany of reasons, but mainly because the audience is finally given a reprieve from Frank’s bottomless well of sadness. Frequently typecast as the jock or the wise-guy, Quaid’s performance here was nothing short of a revelation, a deeply moving turn that matches Moore’s note for Sirkian note.

With Julianne Moore’s stunning performance taking center stage, it was easy to overlook the sterling work of the supporting actors in Haynes’s sublime evocation of 50s film melodrama. But the entire cast of this amazing film (from Patricia Clarkson as the nosy best friend to Viola Davis as the maid) bravely transcended parody and succeeded in imbuing melodramatic archetypes with their own distinctive, modern presence. Perhaps most extraordinary of all was Quaid’s performance as Frank, the not-so-straight-laced husband whose belated emergence from the closet sets the drama in motion. The question of how to pitch a performance in a film that is at least part homage is a tricky one, but Quaid triumphed by delivering a performance of utter sincerity and truthfulness. Frank is not, by any means, a particularly sympathetic character, but the brilliance of Quaid’s interpretation was to illustrate the extent to which Frank’s cruelty and hypocrisy stem from repression, fear and deep self-loathing. By so doing, he uncovered a core of vulnerability in the character that never descended to the level of sentimentality. In one particularly savage scene Quaid even manages to restore shock value to the now-over-used “F”-word (watch for Moore’s shocked reaction). And the pivotal late sequence in which he confesses to Moore’s Cathy that he’s “fallen in love” is a heart-breaker for a litany of reasons, but mainly because the audience is finally given a reprieve from Frank’s bottomless well of sadness. Frequently typecast as the jock or the wise-guy, Quaid’s performance here was nothing short of a revelation, a deeply moving turn that matches Moore’s note for Sirkian note.

JxSxPx's rating:

Ragtime (1981) (2012)

Howard E. Rollins Jr.

As Coalhouse Walker, a man moved to the extreme to defend his dignity and identity in the face of racial prejudice in Forman’s sweeping Ragtime, Rollins is the definition of pride, with all of it’s positive and negative connotations. It’s in the eyes, the high shoulders, the unflinching, regulated tone of voice—the character permeates the actor’s very physicality. But Coalhouse is man who will take only so much, and his breakdown is wrenching to witness and watching this dignified man in his suit and tie lose control and finally, harrowingly, gain it back on his own terms is riveting. It’s no surprise Rollins slipped so well into Sidney Poitier’s shoes as Virgil Tibbs in the TV version of In the Heat of the Night. Like Poitier, Rollins has a stateliness about him, yet with an emotional, damageable core so visible in his words and movement. The look on his face when Coalhouse realizes thugs have defecated in his car is that of confusion and awareness—he’s upset, but his pride won’t let it show. It’s Coalhouse’s tragedy, perhaps, that he doesn’t act on emotion at this initial act and instead lets his rage eat away at him. It’s Rollins’ triumph as a performer that he takes these painful steps down into one man’s hell, and into the shameful history of racism, as delicately as he does. Coalhouse’s eventual busting rage, then, is even more shocking, and somehow so wholly understandable.

As Coalhouse Walker, a man moved to the extreme to defend his dignity and identity in the face of racial prejudice in Forman’s sweeping Ragtime, Rollins is the definition of pride, with all of it’s positive and negative connotations. It’s in the eyes, the high shoulders, the unflinching, regulated tone of voice—the character permeates the actor’s very physicality. But Coalhouse is man who will take only so much, and his breakdown is wrenching to witness and watching this dignified man in his suit and tie lose control and finally, harrowingly, gain it back on his own terms is riveting. It’s no surprise Rollins slipped so well into Sidney Poitier’s shoes as Virgil Tibbs in the TV version of In the Heat of the Night. Like Poitier, Rollins has a stateliness about him, yet with an emotional, damageable core so visible in his words and movement. The look on his face when Coalhouse realizes thugs have defecated in his car is that of confusion and awareness—he’s upset, but his pride won’t let it show. It’s Coalhouse’s tragedy, perhaps, that he doesn’t act on emotion at this initial act and instead lets his rage eat away at him. It’s Rollins’ triumph as a performer that he takes these painful steps down into one man’s hell, and into the shameful history of racism, as delicately as he does. Coalhouse’s eventual busting rage, then, is even more shocking, and somehow so wholly understandable.

All About Eve (1950)

George Sanders

Was there ever a theatre critic as acerbic, as cynical, or as omniscient as Addison DeWitt? In this character screenwriter/director Mankiewicz created a modern archetype by distilling the essential essence of all the critics who ever lived or may yet live. Sanders, the very personification of disenchanted sophistication, was ideally cast in this role: you can feel in Addison’s every word the world-weariness of the actor who would eventually commit suicide at age 65 (leaving behind a note explaining that he decided to end it all because he was bored). Although officially a supporting role, DeWitt provides the very spine of All About Eve: he opens the film with a monologue which identifies the main characters and sets up the conflicts to come, then in the flashback which comprises most of the film reveals himself as the unseen power who controls the action. And perhaps he’s more a mere mortal: there’s a whiff of the demonic in the climactic scene in which DeWitt confronts Eve Harrington with the truth about her past and her meteoric rise to fame. What she learns is that some people sell their souls to the devil for worldly fame and fortune and that with her insane ambition and misplaced belief in her own cleverness Eve has forfeited control over her life and career to the one person in her sphere that is not only smarter, but also more ruthless, than herself.

Was there ever a theatre critic as acerbic, as cynical, or as omniscient as Addison DeWitt? In this character screenwriter/director Mankiewicz created a modern archetype by distilling the essential essence of all the critics who ever lived or may yet live. Sanders, the very personification of disenchanted sophistication, was ideally cast in this role: you can feel in Addison’s every word the world-weariness of the actor who would eventually commit suicide at age 65 (leaving behind a note explaining that he decided to end it all because he was bored). Although officially a supporting role, DeWitt provides the very spine of All About Eve: he opens the film with a monologue which identifies the main characters and sets up the conflicts to come, then in the flashback which comprises most of the film reveals himself as the unseen power who controls the action. And perhaps he’s more a mere mortal: there’s a whiff of the demonic in the climactic scene in which DeWitt confronts Eve Harrington with the truth about her past and her meteoric rise to fame. What she learns is that some people sell their souls to the devil for worldly fame and fortune and that with her insane ambition and misplaced belief in her own cleverness Eve has forfeited control over her life and career to the one person in her sphere that is not only smarter, but also more ruthless, than herself.

JxSxPx's rating:

Robert Shaw

He played villains in The Sting and The Taking of Pelham 123, but as Quint in Jaws, Robert Shaw is an almost inspirational force of nature. The hardscrabble fisherman is a dying breed on Amity Island, a place taken over by tourism. But when the man-eating shark threatens not just the town’s people, but its tourism dollars, Quint is the only one who can help them. Shaw could be chiseled out of stone when he stares down Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) or out into the vast ocean. But his face also splits wide-open with an old drunk’s cackle. There’s certainly an Ahab-esque obsession in Shaw’s eyes as they head out to sea. But it’s not as simple as subbing the white whale for a shark. Quint is out to prove his worth to a changing world he doesn’t fit into. And the shiny-eyed zeal with which Shaw sings old sea shanties, and the sinister snarl he uses to pick class battles with the well-educated Hooper, can be as unnerving as it is fun to watch. But when Quint meets his inevitable end, that’s when Shaw throws the perfect wrench into our view of Quint. Instead of dying with the steely dignity we expect, Shaw’s desperate and depraved terror in the face of death is sad and horrifying. We’re not surprise by Quint’s death, but Shaw reminds us that he knows, in the end, that he was killed in service of a place that had no use for him. Leave it to a skillful actor like Shaw to make someone as surly and misanthropic as Quint not only sympathetic, but likeable.

He played villains in The Sting and The Taking of Pelham 123, but as Quint in Jaws, Robert Shaw is an almost inspirational force of nature. The hardscrabble fisherman is a dying breed on Amity Island, a place taken over by tourism. But when the man-eating shark threatens not just the town’s people, but its tourism dollars, Quint is the only one who can help them. Shaw could be chiseled out of stone when he stares down Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) or out into the vast ocean. But his face also splits wide-open with an old drunk’s cackle. There’s certainly an Ahab-esque obsession in Shaw’s eyes as they head out to sea. But it’s not as simple as subbing the white whale for a shark. Quint is out to prove his worth to a changing world he doesn’t fit into. And the shiny-eyed zeal with which Shaw sings old sea shanties, and the sinister snarl he uses to pick class battles with the well-educated Hooper, can be as unnerving as it is fun to watch. But when Quint meets his inevitable end, that’s when Shaw throws the perfect wrench into our view of Quint. Instead of dying with the steely dignity we expect, Shaw’s desperate and depraved terror in the face of death is sad and horrifying. We’re not surprise by Quint’s death, but Shaw reminds us that he knows, in the end, that he was killed in service of a place that had no use for him. Leave it to a skillful actor like Shaw to make someone as surly and misanthropic as Quint not only sympathetic, but likeable.

JxSxPx's rating:

Christopher Walken

Toiling in a gritty, smoldering Pennsylvania small town’s steel mills has forged a bond between four working-class guys pre-Vietnam portrayed in Cimino’s film, just as much as their pool hall antics and the titular deer hunting practiced during their leisure time has. But, Walken’s Nick possesses a more poetic sensibility that makes him question killing nature’s most beautiful doe-eyed beings—how ironic that Mike’s (Robert De Niro) “one-shot” philosophy would foreshadow future tragedy.

Cut to horrific Viet Cong entrapment. Nick’s emaciated body barely has vital signs, after being ravaged as a P.O.W. Pennsylvanian beer buddy Mike returns to the jungle after the ordeal to salvage Nick from an apocalyptic demise like a Salinger protagonist or good soldier Shweig, Mike plays savior. Nick now resides amongst Saigon’s mini-skirted call girls and gristly con-men. Broken and lost, like a shard buried under a land mine, Nick momentarily flashes on a solitary shred of hope when Mike persuades him to come home before his personal Armageddon—but, it’s too late, and for Nick there is no real “coming back” from the torturous games of Russian roulette he was forced to play by his captors. His harrowing roller-coaster ride tour through ‘Nam leaves him shell shocked and horrified as a nation of boomers, still coming to grips with guilt towards its fallen war heroes from the last war, decides his ultimate fate.

Toiling in a gritty, smoldering Pennsylvania small town’s steel mills has forged a bond between four working-class guys pre-Vietnam portrayed in Cimino’s film, just as much as their pool hall antics and the titular deer hunting practiced during their leisure time has. But, Walken’s Nick possesses a more poetic sensibility that makes him question killing nature’s most beautiful doe-eyed beings—how ironic that Mike’s (Robert De Niro) “one-shot” philosophy would foreshadow future tragedy.

Cut to horrific Viet Cong entrapment. Nick’s emaciated body barely has vital signs, after being ravaged as a P.O.W. Pennsylvanian beer buddy Mike returns to the jungle after the ordeal to salvage Nick from an apocalyptic demise like a Salinger protagonist or good soldier Shweig, Mike plays savior. Nick now resides amongst Saigon’s mini-skirted call girls and gristly con-men. Broken and lost, like a shard buried under a land mine, Nick momentarily flashes on a solitary shred of hope when Mike persuades him to come home before his personal Armageddon—but, it’s too late, and for Nick there is no real “coming back” from the torturous games of Russian roulette he was forced to play by his captors. His harrowing roller-coaster ride tour through ‘Nam leaves him shell shocked and horrified as a nation of boomers, still coming to grips with guilt towards its fallen war heroes from the last war, decides his ultimate fate.

JxSxPx's rating:

Add items to section

Add items to section

The Dark Side

These are the men who confronted, made, or actually were monsters in one way or another. Some are villains, others were just born bad, some still are just misunderstood or a little disturbed, but each actor listed here intrepidly confronts some form of evil.

Carl Boehm

It is now accepted with some historical certainty that Peeping Tom destroyed director Powell’s career. The theater rows like pews were crop-dusted with disgust and vitriol from the film establishment, eager to distance themselves from the film’s transgressive equation of both erotic and violent titillation with the cinema’s inherent voyeuristic gaze. But perhaps the major culprit in the death of the respected British auteur’s career is the killer he cast in the lead, the Austrian-born actor Boehm. Boehm’s performance as quietly disaffected serial killer Mark Lewis was so polite, so gentle, so reserved, and so convincing that it still unsettles today after nearly 50 odd years of three-dimensional villains.

Perhaps what’s so disturbing is how Mark’s dashing Aryan good looks and his shy-schoolboy social anxiety make the audience root for him. The audience’s hope is not for him to succeed in murdering red-headed women, but for him to get away with murder in the hopes that he may one day get away from murder. His suggested, albeit naïve, path to transformation through Moira Shearer’s Vivian, Mark’s stand-in mother figure and a compassionate alternative to his cruel and clinical father figure (played by Powell), seems at times palpable as he desperately attempts to find a connection through Vivian to a humanity not dominated by fear and hypnotized by a life lived through images. In moments with Vivian, Boehm’s Mark appears tortured by his decisions and exuberant at the new possibilities of creating children’s books with her, inventing a new narrative. The fantasy of a second chance is a defiance of typical revenge fantasies, which demand Mark’s corpse at the end. His end then is deeply unsatisfying, particularly in the ways that it perfectly completes the film Mark has been directing his entire life. Though Boehm went on to do some fine work, notably with Fassbinder, his Mark Lewis was his most iconic and perhaps one of the best career-killing performances of all time.

It is now accepted with some historical certainty that Peeping Tom destroyed director Powell’s career. The theater rows like pews were crop-dusted with disgust and vitriol from the film establishment, eager to distance themselves from the film’s transgressive equation of both erotic and violent titillation with the cinema’s inherent voyeuristic gaze. But perhaps the major culprit in the death of the respected British auteur’s career is the killer he cast in the lead, the Austrian-born actor Boehm. Boehm’s performance as quietly disaffected serial killer Mark Lewis was so polite, so gentle, so reserved, and so convincing that it still unsettles today after nearly 50 odd years of three-dimensional villains.

Perhaps what’s so disturbing is how Mark’s dashing Aryan good looks and his shy-schoolboy social anxiety make the audience root for him. The audience’s hope is not for him to succeed in murdering red-headed women, but for him to get away with murder in the hopes that he may one day get away from murder. His suggested, albeit naïve, path to transformation through Moira Shearer’s Vivian, Mark’s stand-in mother figure and a compassionate alternative to his cruel and clinical father figure (played by Powell), seems at times palpable as he desperately attempts to find a connection through Vivian to a humanity not dominated by fear and hypnotized by a life lived through images. In moments with Vivian, Boehm’s Mark appears tortured by his decisions and exuberant at the new possibilities of creating children’s books with her, inventing a new narrative. The fantasy of a second chance is a defiance of typical revenge fantasies, which demand Mark’s corpse at the end. His end then is deeply unsatisfying, particularly in the ways that it perfectly completes the film Mark has been directing his entire life. Though Boehm went on to do some fine work, notably with Fassbinder, his Mark Lewis was his most iconic and perhaps one of the best career-killing performances of all time.

JxSxPx's rating:

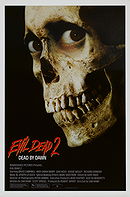

Evil Dead II (1987)

Bruce Campbell

“Groovy”—that’s all you need to know. As Sam Raimi’s retrofitted Stooge, Moe, Larry and Curly all collected in one marvelously manic fake Shemp, lifelong friend Campbell became the physical embodiment of horror comedy. Flashing a jaw-line that just wouldn’t quit and a machismo that masked a lothario’s longing to cut and run, Ash would become a fright flick icon for a demographic of disaffected youth who wanted a far more outlandish superman fighting off demons and the diabolical. Campbell’s performance goes beyond the call of cinematic duty. Required to bring Raimi’s ridiculous ideas to life, we believe the undead chaos in the Evil Dead films for one reason and one reason only—Big Bruce MAKES us believe. In a genre that frequently gets maligned for less than stellar acting, Campbell creates the most unrealistically real champion ever. Groovy, indeed.

“Groovy”—that’s all you need to know. As Sam Raimi’s retrofitted Stooge, Moe, Larry and Curly all collected in one marvelously manic fake Shemp, lifelong friend Campbell became the physical embodiment of horror comedy. Flashing a jaw-line that just wouldn’t quit and a machismo that masked a lothario’s longing to cut and run, Ash would become a fright flick icon for a demographic of disaffected youth who wanted a far more outlandish superman fighting off demons and the diabolical. Campbell’s performance goes beyond the call of cinematic duty. Required to bring Raimi’s ridiculous ideas to life, we believe the undead chaos in the Evil Dead films for one reason and one reason only—Big Bruce MAKES us believe. In a genre that frequently gets maligned for less than stellar acting, Campbell creates the most unrealistically real champion ever. Groovy, indeed.

JxSxPx's rating:

A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984)

Robert Englund

“This is God”, says dream-invading slasher Freddy Krueger, raising a razor-fingered hand, in his first appearance in the popular Nightmare on Elm Street series. Suggesting the primacy of fear and the subconscious over rationality, the Nightmare films provided a dark and much needed tonic to the ascendant 1980s view of adolescence as traumatic but safe. Here the everyday loci and accoutrements of teen life that figure as the backdrop for romance and healthy competition among peers in popular films by John Hughes like Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club become the site of surreal life and death struggles: the teenager’s room, the hot rod, the bathtub, the telephone. Neighborhood teens all start to have the same horrific dreams in which they are terrorized by the burn-scarred Krueger, who has the ability to enter children’s dreams and cause them real harm.

Freddie so dominates the film that it’s surprising to discover how little screen time Robert Englund has as the villain. Add to that the fact that Freddie is more conglomeration of effects (heavy facial makeup, elongated arms, sepulchral voice altered in post-production) and metonymic paraphernalia (the crumpled fedora, the striped sweater, and of course the finger-razor gloves) than character, and it’s all the more striking that Englund makes the role cohere as the embodiment of all teenage fears. Part Lucifer, part Pee Wee Herman, Englund delivers Krueger’s simultaneously murderous and lecherous dirty-old-man taunts so they play for sick laughs, but also resonate as the fodder of the teen subconscious. “I’m your boyfriend now, Nancy”, he says to the heroine through a phone that has morphed into a lolling, lascivious tongue. Englund has reprised the role many times since, most effectively in New Nightmare (1994), but never with the same primal terror of this initial performance.

“This is God”, says dream-invading slasher Freddy Krueger, raising a razor-fingered hand, in his first appearance in the popular Nightmare on Elm Street series. Suggesting the primacy of fear and the subconscious over rationality, the Nightmare films provided a dark and much needed tonic to the ascendant 1980s view of adolescence as traumatic but safe. Here the everyday loci and accoutrements of teen life that figure as the backdrop for romance and healthy competition among peers in popular films by John Hughes like Sixteen Candles and The Breakfast Club become the site of surreal life and death struggles: the teenager’s room, the hot rod, the bathtub, the telephone. Neighborhood teens all start to have the same horrific dreams in which they are terrorized by the burn-scarred Krueger, who has the ability to enter children’s dreams and cause them real harm.

Freddie so dominates the film that it’s surprising to discover how little screen time Robert Englund has as the villain. Add to that the fact that Freddie is more conglomeration of effects (heavy facial makeup, elongated arms, sepulchral voice altered in post-production) and metonymic paraphernalia (the crumpled fedora, the striped sweater, and of course the finger-razor gloves) than character, and it’s all the more striking that Englund makes the role cohere as the embodiment of all teenage fears. Part Lucifer, part Pee Wee Herman, Englund delivers Krueger’s simultaneously murderous and lecherous dirty-old-man taunts so they play for sick laughs, but also resonate as the fodder of the teen subconscious. “I’m your boyfriend now, Nancy”, he says to the heroine through a phone that has morphed into a lolling, lascivious tongue. Englund has reprised the role many times since, most effectively in New Nightmare (1994), but never with the same primal terror of this initial performance.

JxSxPx's rating:

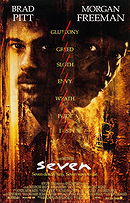

Seven (1995)

Morgan Freeman and Brad Pitt

Fincher’s unwieldy Se7en slices at your sensibilities like a bayonet, in no small part due to the fantastic coupling of Freeman and Pitt. Freeman’s William Somerset steps into each scene with an intellectual rigor that counterbalances a jaded perspective on life. He is the perfect foil to Pitt’s Detective David Mills, a young, cocky, impetuous cop who has just transferred into hell. Seven days before Somerset’s retirement, he and his new partner catch a case in which serial killer John Doe (Kevin Spacey) begins to kill his victims based on the biblical seven deadly sins. Gwyneth Paltrow appears as Detective Mills’ homesick wife Tracy, who seeks out advice from Somerset’s character on how to deal with the misery inflicted upon her by the soulless city that she has been forced to move to. And indeed the city is soulless. It’s a quagmire of misery that will pull the weak and weary into a black hole of desolation. Freeman and Pitt struggle with each other, John Doe, and even the city itself to defeat it.

But alas, that is not the case as Se7en ends with a doozy of a finale—- with a surprising twist and a head in a box. The audience is then left to try and reconcile a devastating sense of gross alienation and perversity. Grossing over $300 million dollars worldwide, Se7en‘s existential horror-fest was no doubt rendered more profound due to the extraordinary talents of both Freeman and Pitt. Both actors have an enviable array of films that showcase their unique abilities as leading men, but their shared responsibility for this film laid the foundation for its success. Freeman’s subtle ferocity and Pitt’s blustery bullheadedness ground the outrageous proceedings and succeed in immortalizing of one of the greatest thrillers of the last 30 years.

Fincher’s unwieldy Se7en slices at your sensibilities like a bayonet, in no small part due to the fantastic coupling of Freeman and Pitt. Freeman’s William Somerset steps into each scene with an intellectual rigor that counterbalances a jaded perspective on life. He is the perfect foil to Pitt’s Detective David Mills, a young, cocky, impetuous cop who has just transferred into hell. Seven days before Somerset’s retirement, he and his new partner catch a case in which serial killer John Doe (Kevin Spacey) begins to kill his victims based on the biblical seven deadly sins. Gwyneth Paltrow appears as Detective Mills’ homesick wife Tracy, who seeks out advice from Somerset’s character on how to deal with the misery inflicted upon her by the soulless city that she has been forced to move to. And indeed the city is soulless. It’s a quagmire of misery that will pull the weak and weary into a black hole of desolation. Freeman and Pitt struggle with each other, John Doe, and even the city itself to defeat it.

But alas, that is not the case as Se7en ends with a doozy of a finale—- with a surprising twist and a head in a box. The audience is then left to try and reconcile a devastating sense of gross alienation and perversity. Grossing over $300 million dollars worldwide, Se7en‘s existential horror-fest was no doubt rendered more profound due to the extraordinary talents of both Freeman and Pitt. Both actors have an enviable array of films that showcase their unique abilities as leading men, but their shared responsibility for this film laid the foundation for its success. Freeman’s subtle ferocity and Pitt’s blustery bullheadedness ground the outrageous proceedings and succeed in immortalizing of one of the greatest thrillers of the last 30 years.

JxSxPx's rating:

Blue Velvet (1986)

Dennis Hopper

They all considered it too vulgar and intense—Robert Loggia, Richard Bright, and Willem Dafoe. But when director Lynch met with the former Easy Rider rebel about playing the vile villain in his new film, Hopper stunned the soft spoken director. “I am Frank Booth” he exclaimed, and one of the classic horrors of modern cinema was born. Hopper embraced the inherent evil in craven criminal Frank, formulating the switchover from helium to amyl nitrate in the notorious “breathing device”, as well as intensifying the “relationship” between the hood and his fey cohort, the Roy Orbison crooning Ben (played brilliantly by Dean Stockwell). After years far outside the mainstream, Hopper soon found his flagging career back on track—and it’s not hard to see why. Frank Booth is the kind of career defining turn that both relies on and accents an actor’s specialized strengths. In the case of Hopper, the combination of clear-cut evil and the sense memory manipulation of a decade lost in a drug-fueled haze meshed into one of the most remarkable expressions of depravity ever captured.

They all considered it too vulgar and intense—Robert Loggia, Richard Bright, and Willem Dafoe. But when director Lynch met with the former Easy Rider rebel about playing the vile villain in his new film, Hopper stunned the soft spoken director. “I am Frank Booth” he exclaimed, and one of the classic horrors of modern cinema was born. Hopper embraced the inherent evil in craven criminal Frank, formulating the switchover from helium to amyl nitrate in the notorious “breathing device”, as well as intensifying the “relationship” between the hood and his fey cohort, the Roy Orbison crooning Ben (played brilliantly by Dean Stockwell). After years far outside the mainstream, Hopper soon found his flagging career back on track—and it’s not hard to see why. Frank Booth is the kind of career defining turn that both relies on and accents an actor’s specialized strengths. In the case of Hopper, the combination of clear-cut evil and the sense memory manipulation of a decade lost in a drug-fueled haze meshed into one of the most remarkable expressions of depravity ever captured.

JxSxPx's rating:

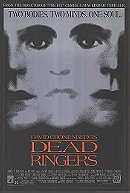

Dead Ringers (1988)

Jeremy Irons

While accepting his Oscar for Barbet Schroeder’s Reversal of Fortune, Jeremy Irons said, “... some of you may understand why—thank you David Cronenberg”. Those who did understand knew that the staid Academy of the ‘80s just couldn’t bring itself to reward the perverse, deeply disturbing performance Irons had given in Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers, and many felt Iron’s Reversal win was overdue acknowledgement of his brilliant performance in Ringers. Irons plays twin gynecologists Beverly and Elliot Mantle, brothers who share a medical practice, lover, and a drug-fueled descent into madness. What makes his portrayal remarkable, aside from his skill in acting opposite himself, are the small details—looks, gestures, and phrasing—that make each character distinguishable while still making the twins virtually identical. It is a chilling performance that would understandably make any woman reluctant to ever go to the gynecologist again, but Irons doesn’t emphasize the creepiness factor. Instead, he plays to normality; even as the twins’ instability grows, they follow what is, to them, a logic and reasoning that justify their depraved and deadly decisions. In one simple scene, Beverly and Elliot walk in a haze through their apartment, one behind the other, in perfect unison with eerily identical expressions. In the age before CGI, the scene required the best special effect to be effective: great acting that is precise and wholly believable. It is this quality of acting that infuses every frame of Iron’s performance and makes the Mantle brothers two of the most complex and frightening characters to grace a movie screen.