Slant’s 100 Best Film Noirs of All Time

Sort by:

Showing 1-50 of 100

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

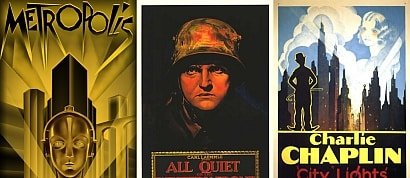

Purists will argue that film noir was born in 1941 with the release of John Huston’s The Maltese Falcon and died in 1958 with Marlene Dietrich traipsing down a long, dark, lonely road at the end of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil. And while this period contains the quintessence of what Italian-born French film critic Nino Frank originally characterized as film noir, the genre has always been in a constant state of flux, adapting to the different times and cultures out of which these films emerged.

Noir came into its own alongside the ravages of World War II, with the gangster and detective films of the era drastically transforming into something altogether new as the aesthetics of German Expressionism took hold in America, and in large part due to the influx of German expatriates like Fritz Lang. These already dark, hardboiled films suddenly gained a newfound viciousness and sense of ambiguity, their dangers and existential inquiries directed at audiences through canted camera angles and a shroud of smoke and shadows.

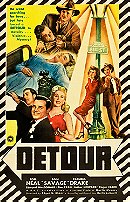

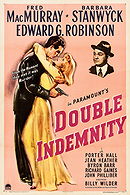

As the war reached its end stage, soldiers came home to find a once-unquestioned era of male authority put in the crosshairs of changing cultural norms. And in lockstep, the protagonists of many a noir began to feel as if they were living in a newly vulnerable world, taking cover beneath trench coats and fedoras, adopting cynical, wise-cracking personae, and packing heat at all times while remaining hyper-aware of the feminine dangers that surrounded them. Jean-Luc Godard once said that “all you need for a movie is a gun and a girl,” and in noir, the latter was often the most dangerous. Indeed, Barbara Stanwyck’s anklet in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity and Ann Savage’s icy stare in Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour are as deadly as any bullet.

Our list acknowledges the classics of the genre, the big-budget studio noirs and the cheapest of B noirs made on the fringes of the Hollywood studio system. But we’ve also taken a more expansive view of noir, allowing room for supreme examples of the proto-noirs that anticipated the genre and the neo-noirs that resulted from the genre being rebooted in the midst of the Cold War, seemingly absorbing the world’s darkest and deepest fears. Then and now, the best examples of this genre continue to evoke—shrewdly and with the irrepressible passion of the dispossessed—humanity’s eternal fear of social disruption. Derek Smith

Noir came into its own alongside the ravages of World War II, with the gangster and detective films of the era drastically transforming into something altogether new as the aesthetics of German Expressionism took hold in America, and in large part due to the influx of German expatriates like Fritz Lang. These already dark, hardboiled films suddenly gained a newfound viciousness and sense of ambiguity, their dangers and existential inquiries directed at audiences through canted camera angles and a shroud of smoke and shadows.

As the war reached its end stage, soldiers came home to find a once-unquestioned era of male authority put in the crosshairs of changing cultural norms. And in lockstep, the protagonists of many a noir began to feel as if they were living in a newly vulnerable world, taking cover beneath trench coats and fedoras, adopting cynical, wise-cracking personae, and packing heat at all times while remaining hyper-aware of the feminine dangers that surrounded them. Jean-Luc Godard once said that “all you need for a movie is a gun and a girl,” and in noir, the latter was often the most dangerous. Indeed, Barbara Stanwyck’s anklet in Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity and Ann Savage’s icy stare in Edgar G. Ulmer’s Detour are as deadly as any bullet.

Our list acknowledges the classics of the genre, the big-budget studio noirs and the cheapest of B noirs made on the fringes of the Hollywood studio system. But we’ve also taken a more expansive view of noir, allowing room for supreme examples of the proto-noirs that anticipated the genre and the neo-noirs that resulted from the genre being rebooted in the midst of the Cold War, seemingly absorbing the world’s darkest and deepest fears. Then and now, the best examples of this genre continue to evoke—shrewdly and with the irrepressible passion of the dispossessed—humanity’s eternal fear of social disruption. Derek Smith

In a Lonely Place (1950)

Throughout In a Lonely Place, Nicholas Ray complements Humphrey Bogart’s performance with an atmosphere of closed-off stagnation that would prove greatly influential to such self-conscious, meta-textual noirs as The Long Goodbye, L.A. Confidential, and Mulholland Drive. Ray exhibits a matter-of-fact mastery of tone that would become a trademark in his work. In a Lonely Place is a tricky thriller that’s understated in its exploration of the theme of dream versus reality that governs most Hollywood-set mysteries. Like all insecure, domineering control freaks, Dixon (Bogart) must be the big fish of his own pond. It’s a pond that can house no other fish, and he chafes at the stifling limitations of this prison while feeling incapable of reaching beyond it. His one attempt to escape it, pulling Laurel (Gloria Grahame) into his own hell, proves unsuccessful, and we’re as grateful for her as we are heartbroken for him. And it’s this double awareness that informs In a Lonely Place with the irresolvable heft of tragedy. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Out of the Past (1947) (1948)

It makes sense that one of the darkest and truly existentialist noir films was directed by Jacques Tourneur, a director otherwise known best for brooding horror films like Cat People and I Walked with a Zombie, and who, a native of France, shared a homeland with existentialism. As played by Robert Mitchum, protagonist Jeff Bailey projects a coolness that shades into a passive acceptance of fate. When an unexpected and obviously threatening figure from his secret past appears in the small Nevada town he’s been hiding out in, Jeff shows almost no reaction, as if he always expected his sins to catch up with him. Thrust back into a world he had played a key role in shaping—one lorded over by the gangster Whit (Kirk Douglas in one of cinema’s juiciest villain roles)—Jeff makes an effort to escape again, but Mitchum’s characteristic heavy eyelids and laconic performance make it seem as if the man’s just sleepwalking through the motions. Jeff represents the existentialist hero par excellence, the man who defies fate, paradoxically, by accepting it, staring it impassively in the face. Brown

JxSxPx's rating:

The Big Sleep (1946)

The squalid, damp well from which Kiss Me Deadly, The Long Goodbye, and Inherent Vice emerge, Howard Hawks’s The Big Sleep is the apotheosis of the Los Angeles-set crime film, the movie to cement the city’s upper-crust neighborhoods as convoluted webs of corruption and murder. Set in foggy, depopulated west-side backroads and suspiciously spotless mansions, the story never leaves the swaggering company of Phillip Marlowe (Humphrey Bogart), a devastatingly cool private eye who’s been promised good money to settle a potential blackmail case weighing over the head of beautiful heiress Vivian Rutledge (Lauren Bacall). As crooked gamblers, shady dames, and moneyed crime leaders pile up, each pointing to a new set of possible culprits, Marlowe finds himself inexorably pulled into Vivian’s radiant orbit even as every other dazzling woman he encounters throws herself at him. This being a Hawks film, the chemistry between the two characters never flourishes into full-blown romance and often resembles something much more platonic or even familial, and yet it’s all the more spellbinding because of that unfulfilled potential. The Big Sleep is a film that tantalizingly grooves around the edges of things—sex, knowledge, L.A.’s polite society, the very meaning behind the big network of clues and red herrings—and leaves you content to wallow in the murk. Lund

JxSxPx's rating:

The Third Man (1949)

Carol Reed’s The Third Man, like many of the era’s seminal noirs, examines a modern post-war environment where people’s lives are treated as nothing more than a means to financial success (see also Billy Wilder’s Double Indemnity, the murder plot of which literally boils a man’s life down to a dollar amount). By utilizing the German-inspired visual techniques of wide shots, canted angles, jagged architecture, and expressionistic chiaroscuro lighting, directors like Reed and Wilder created an environment of spatial and moral confusion in which their pulpy narratives could take on the ethical weight of a biblical proverb. As Harry Lime (Orson Welles) attempts to escape from the police in the sewers of Vienna, he grasps helplessly up through a sewer grate at a light he can’t reach, and the effect is that of the wicked being denied entrance into heaven. And in The Third Man, such an image isn’t even remotely silly; it’s pure, devastating and vital, just as much now as it was then. Matt Noller

JxSxPx's rating:

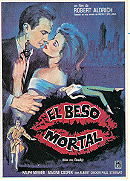

Kiss Me Deadly (1955)

Calling Kiss Me Deadly one of the darkest detective thrillers ever made, or the ultimate film noir, doesn’t do it justice. Robert Aldrich’s adaptation of Mickey Spillane’s novel doesn’t merely exemplify those two genres and identify the places where they overlap. It defines the difference between cynicism and nihilism, then throws down with the nihilists, if for no other reason than to show you what it means to live in a world where nothing matters. Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) has a suit and car, plus the power of speech, but that’s about all that separates him from any other randy carnivore that ever walked the earth. Aldrich’s high-contrast, super-dark images and crazy Dutch angles push noir conventions to cartoon extremes; in earlier noirs, these visual affectations implied moral instability, but here their exaggeration signifies a moral vacuum bereft of ethical and spiritual moorings. The exact nature and purpose of the “great whatsit” is never satisfactorily explained, but its eventual appearance—accompanied by one of the greatest and most lovingly imitated Pandora’s Box images in film history—makes for a perfect ending. Matt Zoller Seitz

JxSxPx's rating:

Touch of Evil (1958)

Retrospectively, The Lady from Shanghai plays as a rough draft for Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, as it similarly operates as the audio-visual equivalent of a draftsman’s sketchbook, with the nearly incoherent plot serving as a springboard for a variety of self-contained vignettes, ostentatiously symbolic shots, motifs, and probable ideas for future projects. But if The Lady from Shanghai coasts, Touch of Evil soars, as it’s charged by a bracing sense of autobiographical grandeur. In short: Welles’s desperation as an artist at the mercy of a hypocritical studio regime merges here with the desperation of his socially entrapped characters. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

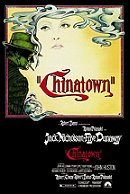

Chinatown (1974)

With Chinatown, director Roman Polanski and writer Robert Towne fashioned a multifaceted morality play that spoke both to a specific (and enduring) history of violence and corruption in the City of Angels and, more broadly, to the disenchanted orphans of the Summer of Love: “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.” If this terse ode to futility came to be recognized as one of the great final lines in film history, it’s because few others so succinctly addressed the tenor of their times—in this case, the downbeat mood exuded like a malign miasma by New Hollywood cinema in the mid-1970s, a world-weary shrug of resignation. Despite the film’s forgivably literal ending, Chinatown was never meant as an actual destination, so much as a state of mind, a country of vague terrain where the customs are alien, motivations always suspect, and the only thing you can depend on is that no good deed will go unpunished. Hence this exchange: “What did you do there?” “As little as possible.” Budd Wilkins

JxSxPx's rating:

The Big Heat is a feast of resonant terseness, and its subject is ultimately what’s pointedly missing from it until the heartbreaking ending: sullied, qualified compassion, in a prosperous world with a foundation deeply eaten up by hypocrisy and corruption. Lang doesn’t make a pretense of decrying vengeance, and he doesn’t valorize it either, offering it up matter-of-factly as shit that happens. Every character in the film shares Lang’s frankness, his forwardness, which refuses to apologize for human will. This bracing maturity might also be linked to the artist’s real experience with fascism: He accepts chaos as inherent, and he has no patience for children’s piety. The Big Heat is truly a hard-boiled film, and its nastiness cleanses the noir of the masculine self-pity that often lards the genre. These men aren’t victims or patsies, particularly of women, who are endlessly destroyed in this film; they’re vicious movers and shakers who go to war purposefully, for their own reasons. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

The Long Goodbye (1973)

Simultaneously an act of revisionism as well as a parody of then-revitalizing neo-noir, Robert Altman’s adaptation of pulp legend Raymond Chandler’s The Long Goodbye is perhaps the director’s most audacious act of genre deconstruction in a career filled with contenders, most of which are accompanied by ampersands: McCabe & Mrs. Miller, O.C. & Stiggs, and Vincent & Theo. There’s no “and” to pair off with Elliot Gould’s interpretation of Philip Marlowe. Though the film opens on a note of camaraderie and trust between Marlowe and his friend Terry Lennox (Jim Bouton), who appears to be in a major pinch but who Marlowe whisks to Tijuana no questions asked, the rest of the film punctuates the complete dislocation of traditional noir masculinity from the cultural snooze button that was post-1960s California. In Chandler’s books, Marlowe’s composure in rat-a-tat-tat surroundings was cool and disarming. In Altman’s Los Angeles of Hemingway knock-offs, thousand-dollar-a-day psychiatric playground retreats, Barbara Stanwyck-impersonating parking attendants, cats with gourmet tastes, and topless Yoga bimbos with a penchant for pot brownies, Marlowe’s persona is not only a relic, it’s nearly uncool. Henderson

JxSxPx's rating:

There’s a fragility to Detour that only strengthens its spell. Edgar G. Ulmer’s 1945 film is an inventively sparse mixture of docudrama and DIY expressionism: There are no lush sets and camera pirouettes on display here, as Ulmer makes do with found settings, isolated props, and abbreviated, shaky tracking shots that are rich in authentic and incidental textures. There is tension between edits that cobble sometimes mismatched takes together, meaning that one can almost feel the work that’s necessary here to sustaining an illusion with limited means. Detour has a fly-by-night intensity, then, that’s derived by the thinning of the distance between the film’s collaborators and the audience, suggesting the fluid quality of live art, particularly theater and musical concerts, with the gutter vitality of pulp fiction at its most wrenchingly subjective. Bowen

Double Indemnity (1944)

This is the blueprint for a certain kind of film noir, where the perfect crime comes undone by the protagonists’ greed and paranoia. Its dialogue is the perfect mix of hard-boiled poetry and acidic wit: “How could I have known that murder can sometimes smell like honeysuckle?” So asks insurance salesman Walter Neff (“Two f’s, like in Philadelphia, if you know the story”) just before meeting his irresistible soon-to-be accomplice, Phyllis Dietrichson, who happens to be unhappily married to a rich, older man. Played by Barbara Stanwyck, Phyllis is the textbook femme fatale, all cold calculation beneath an exterior that promises untold delights to the man who can win her. No one in Billy Wilder’s film, based on the novel by James M. Cain and co-written by Raymond Chandler, is as smart as they think they are, but everyone is weaker and more dishonest than they appear. Released in 1944, during the height of WWII, Wilder’s pitch-black vision of human treachery and moral failure is only lightened by the film’s surrogate family relationships. Walter tries to be a good father figure to Phyllis’s orphaned stepdaughter and a good son to his boss (Edward G. Robinson). If our relationships have doomed us to this catastrophe, Wilder implies, maybe the ones we salvage from the wreckage of the war can save us all. Ivanov

JxSxPx's rating:

Pickup on South Street (1953)

The world of Pickup on South Street is familiar to admirers of Samuel Fuller’s other films, abounding in a lurid cavalcade of unforgettable oddballs who collectively show America to be a place of cracked schemers and dreamers working for their own interests. Like many crime-film directors, Fuller regards his crooks fondly as the people who’re willing to see America for what it is and play by the real rules accordingly, while the cops are hypocrites who hide their prudish self-righteousness behind their badges. There’s a weird, fascinating conflict of politics in Fuller’s vision, as it glorifies both an informal socialism as well as an ethos that’s most typically described as survival of the fittest. The criminals sell each other out, particularly in a wonderful running gag with professional stoolie Moe Williams (Thelma Ritter), but warn each other about said sell-outs, holding no grudges, while eventually dying to protect others. On top of this contradiction, Fuller grooves on a definitively masculine urge to behave as a metaphorical alley cat, doing whatever the hell you like, precisely for the hell of it. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Against the grain of what we might assume about put-upon little guys in movies and the way they eventually lash out, Fritz Lang actually only dwells on the tableaux of Chris Cross’s (Edgar G. Robinson) eunuchized doldrums to make one almost invisible moment work—when, over a pair of Rum Collinses with Kitty March (Joan Bennett), the man doesn’t really correct her when she makes the fateful assumption that he’s some kind of big-shot famous painter. Jean Renoir and Lang shared an interest in watching the human animal in his or her natural habitat, while underlining, whenever possible, the elaborate mechanics that governed their interactions, their movement through society, and the changes they underwent across epochal time. There are essential differences, however. Renoir, during his first celebrated period of the early and middle 1930s, was quite comfortable with the jovial profanity of Michel Simon’s layabouts, as well as the pre-Method fury of Jean Gabin’s crumpled heroes. On the other hand, Lang’s photographic precision indicated that he was more concerned with pivotal dramatic moments, the lightning crashes that, even if they might be forgotten (as Cross’s first run-in with Dan Duryea’s rangy pimp Johnny Prince is quickly put out of the film’s mind), tend to signal a sea change in the lives of all concerned. Christley

JxSxPx's rating:

John Huston was one of those directors who seemed to arrive on the scene fully formed. His iconically hard-boiled first film, The Maltese Falcon, made small-time gangster actor Humphrey Bogart into Humphrey Bogart, the world-weary, sarcastic, small but tough, crass but romantic persona he’d inhabit for much of his career. The plot of the film, in which the falcon-statuette MacGuffin isn’t even mentioned until well into the second act, is almost beside the point; the interactions between Bogart’s Sam Spade and the cast of eccentric characters that parade through his office is what makes the film. Spade exhibits an almost inscrutable obstinacy regarding anyone’s interests but his own, defying and mocking the police with the same casual disdain as he does the nefarious gangster Kasper “The Fat Man” Gutman (Sydney Greenstreet). Considering how much of The Maltese Falcon takes place in Spade’s office, it’s a credit to the direct snappiness of Huston’s script and direction—akin to the pared-down modernism of Ernest Hemingway (or Dashiell Hammett)—that the film remains one of the most riveting and downright fun noir films. Brown

JxSxPx's rating:

Sweet Smell of Success (1957)

Contorting words, loyalties, perspectives, and truths is second nature for a high-powered New York City columnist, J.J. Hunsecker (Burt Lancaster), and his publicist lackey, Sidney Falco (Tony Curtis). There are no heroes in Sweet Smell of Success, just victimizers and victims. Often, key characters inhabit both roles simultaneously, with the sleek and sly Sidney fitting this mold perfectly. One second Sidney’s a sweet talker, the next he’s gutting your character from the inside out, and it’s this type of back and forth that makes the film so enthralling. Alexander Mackendrick’s visuals are ever-bustling as they survey the city, but they take on a balmy thousand-yard stare during interiors, planting next to characters in almost devotional static shots as they berate each other to a bloody pulp. And its that almost elemental focus on how people poison each other’s that makes the film such a virtuosic, damning, and, above all else, intoxicating portrait of American power lust. Heath

JxSxPx's rating:

On Dangerous Ground (1951)

Perched between late-‘40s noir and mid-‘50s crime drama, On Dangerous Ground is one of the great, forgotten works of the genre. Jim Wilson (Robert Ryan) is a time-bomb of a New York cop, tormented by the urban squalor he sees around him; after roughing up one too many crooks, he’s assigned to track down a killer in wintry upstate, where he falls for Mary Malden (Ida Lupino), the main suspect’s blind sister. Easily mushy, the material achieves a nearly transcendental beauty in the hands of Nicholas Ray, a poet of anguished expression: The urban harshness of the city is contrasted with the austere snowy countryside for some of the most disconcertingly moving effects in all film noir. Despite the violence and the steady intensity, this is a remarkably pure film. Croce

Sunset Boulevard (1950)

The savage creature that is aging screen legend Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Sunset Boulevard sees the cinema as a once-miraculous fountain of youth, diluted and muddied by technology and what she sees as false ambition. The character’s fury is aimed at the advent of talkies and the new talent that it requires, but said talent merely serves as the perfect patsy to distract from the actress’s own limitations and her stalling indulgence in the comforts of fame and praise. in an exquisite early scene, Desmond and her devoted house servant, Max (Erich von Stroheim), run Queen Kelly, von Stroheim’s masterful late silent, which starred Swanson, for Gillis in a private screening room, and the screen comes to glowing life as a young Swanson makes a prayer with candles. The beauty of the subject and the beauty of how the subject is framed are inseparable in Queen Kelly, as in most great films. Beauty may become a more subjective term in the face of Sunset Boulevard, but it’s no less a masterpiece than von Stroheim’s film, and when Wilder catches Olson at just the right angle, and just the right light, the two films share a common beauty. More importantly, it becomes clear that those artists with propensities for great beauty and greater insight see beyond both technical innovations and limitations, and are never in need of a close-up to validate their abilities. Cabin

JxSxPx's rating:

The Lady from Shanghai (1947)

The Lady from Shanghai plays as a rough draft for Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, as it similarly operates as the audio-visual equivalent of a draftsman’s sketchbook, with the nearly incoherent plot serving as a springboard for a variety of self-contained vignettes, ostentatiously symbolic shots, motifs, and probable ideas for future projects. There’s the long commanding scene where Michael (Welles) and Arthur (Everett Sloane) discuss the benefits and perils of money that ends, in true Welles fashion, with the villain making the most sense. There’s the tranquil, baked-in sexual evil of the entire boat-trip sequence, which culminates in a ravishingly suggestive horizontal shot of a two-piece-clad Elsa (Rita Hayworth), and which appears to have later informed the tone of Roman Polanski’s Knife in the Water. There’s the great absurd courtroom scene that climaxes with Arthur cross-examining himself, and, of course, there’s the legendary hall-of-mirrors shoot-out, which is known by people who haven’t even seen the film. The cherry on top of this huge melting sundae is the dialogue at large, which is almost entirely composed of quotable only-in-the-movies luxury super-star bon mots: “You need more than luck in Shanghai”; “You’ve been traveling the world too much to find out anything about it”; “Everybody is somebody’s fool”; and so forth. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

The Night of the Hunter (1955)

The Night of the Hunter is so loaded with neurotic symbology that it can accommodate nearly any meaning any generation wishes to assign to it, and that’s the source of its uneasy, primordial power. The film is a nightmare coming-of-age story that concerns a child who learns that adults (and, by extension, their rules) aren’t only fallible, but given to pronounced malevolence. The imagery heightens our impression of John Harper (Billy Chapin) and his little sister Pearl’s (Sally Jane Bruce) feelings of exclusion from society following the boy’s rude social awakening. Nearly every shot communicates a sense that the actors are pointedly divorced from their surroundings. Robert Mitchum doesn’t exactly play Reverend Harry Powell as an evil deity, but as a self-entitled child who feels that he should have whatever he wants because he makes a pretense of being in the “god business” with the reverend shtick. Mitchum lets you see Harry’s absurdity, and thus his humanity, which only allows him to grow larger in your thoughts as a figure of terror, an agent of unquantifiable reckoning who reveals that faith is only as noble, or as diseased, as its practitioner. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Laura (1944)

Laura (Gene Tierney) isn’t a real character for two-thirds of Otto Preminger’s film, only talked about, remembered, eroticized and gazed upon as an image of unfathomable beauty. She’s an illusion, a reflection of what every wants to see in her. Yet even when she reappears, she still isn’t treated as a real character in her first few minutes of screen time. Before McPherson wakes up, Preminger’s camera, which glides upon the dozing detective within the completely static apartment, gives the impression that he’s possibly entering a dream state. When Laura walks into her apartment and detective Mark McPherson (Dana Andrews) does a double take, it’s equally difficult for the viewer to accept her corporeal presence. This moment is beautifully climactic of a truth the film has been hinting at, through the considerate, yearning score that swells as the hardboiled McPherson searches her apartment, reads her private letters, smells her clothes, and tries to “know” the missing Laura: He’s fallen in love with a dead woman. Newspaper columnist Waldo Lydecker’s (Clifton Webb) derision is spot on: “You’d better watch out, McPherson, or you’ll finish up in a psychiatric ward. I doubt they’ve ever had a patient who fell in love with a corpse.” The premise is prematurely Hitchcockian, and in Preminger’s hands such obsessive love is simply, irrefutably tragic, a result of failed patriarchal domination. Tina Hassania

JxSxPx's rating:

Shoot the Piano Player (1960)

Shoot the Piano Player gives the film noir a peculiar, self-reflexive spin. François Truffaut’s film reiterates the genre’s multifold sins against women—its stylization of them as alluring objects, its fear of their sexual agency, and its almost ritualistic sacrifice of them—but with both self-consciousness and a bad conscience. Almost every male character expresses an unsolicited opinion about women, often at comically dissonant moments, as when Charlie and Léna’s (Charles Aznavour and Marie Dubois) kidnappers strike up a conversation about gender relations while they hold the pair at gunpoint in the car. Charlie, rather than the brusquely masculine noir hero of yore, is insecure (he has to buy self-help books on conquering shyness) and broken up about the suicide of his wife—which, in his former life as famed concert pianist Edouard Saroyan, he helped cause with his jealousy. In the end, it’s not the femme fatale who’s punished, but the innocent woman, doomed by the perverse hypermasculinity of Charlie’s gangster brothers. Truffaut’s ironic, breezy film is not not sexist, but it also is not unaware of its genre’s guilt. Brown

Le Samourai (1967)

Jean-Pierre Melville’s films celebrate code of conduct as a self-justifying reward—a notion that enjoys less currency in our self-absorbed present day. And so Le Samouraï is driven by the subterranean merger between Jef Costello (Alain Delon) and Melville’s working credos. Jef derives satisfaction from his sense of style, which fuses dandy poetry with a working man’s enjoyment of the quotidian. As played, or more accurately inhabited, by one of the most beautiful men in cinema, Jef wears his fedora, trench coat, and white gloves with the precision of a model, adjusting his hat with a dancer’s grace, its brim seemingly ready to slice through metal. But Jef also steals cars and barters with middlemen of the criminal underworld, revealing the grit and the teeth that reside underneath his neat and nearly androgynous presence. Jef fingers a ring of keys, used for stealing cars, with a grace that weds white- and blue-collar modes of sexuality. He’s dancer, mechanic, killer, and high-stakes thief all in one, an antihero for people of all classes, who’re governed by all erotic hungers. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Blue Velvet (1986)

Cut and dried, Blue Velvet rolls together David Lynch’s two diametrically opposed, but indivisible, views of American life: One is the “white picket fences” façade, the other its grimy, badly infected underbelly. None approach his film in terms of tone and control, the fusion of unlike halves mastered with a kind of honest-faced plainness that was, in some ways, the one truly unprecedented part of Lynch’s personality, up to that point expressed most freely in the organic perversions of Eraserhead and the claustrophobic industrial cityscapes of The Elephant Man. A conventionally appealing quality of Blue Velvet is the way its “plunge” into dark territories from unambiguously bright ones (played out twice, once in montage, then more gradually in narrative) is hitched to a character (played by Kyle MacLachlan) by two classic dramatic hooks: the plucky young detective trying to solve a mystery and the good-faced young boy who’s trying to win the heart of the town’s prettiest girl. But these things, in fact the whole dramatic trajectory, seem incidental to the way the images of Lumberton and its various inner zones are a lot like Lynch’s work sculpture and painting, ever infused with the inner life of nightmares, with an exploded chicken here and a baby-doll head there. Christley

JxSxPx's rating:

The ever-widening moral and societal implications of the seemingly simple conceits that John Cassavetes’s narratives rotate on are hardwired into the physical and conversational liberation of his performers. The tremendous emotions summoned are rarely confronted directly, but are elicited through the wild-eyed, strikingly instinctive imagery. In The Killing of a Chinese Bookie, there’s a great cut between Cosmo (Ben Gazzara) being approached by gangsters and the planning of the titular crime in a corner booth. We don’t see the criminals him-haw around their demands, because the John Cassavetes skips over the oft-obligatory lead-ins to discussions of murder. What we get is a clear sense of the filmmaker’s distaste for killers who play coy to mask their monstrous intentions, but also a keen avoidance of reiterating what has led Cosmo to this fate. Cassavetes respects these criminals as characters, but he doesn’t wish to luxuriate in their company any more than he has to. Chris Cabin

JxSxPx's rating:

Watergate-era paranoid thrillers are defined by their sense of overwhelming despair at confronting the caprice of institutional power, with an emphasis on their protagonists’ total helplessness when they rock the boat, only to discover just how many career- and life-crushing resources their foes have at their disposal. Night Moves is an outlier in this respect, defined by the weary depression of the cynic whose worst predictions have been confirmed. It stresses the indignity of learning how small one really is, and one can scarcely blame Gene Hackman’s Moseby for emotionally sealing himself from the world. As the film’s mystery gradually unfurls and becomes increasingly grotesque, however, Moseby is shaken from his detachment, increasingly invested in revealing the truth even as his dedication only seems to open him up to be battered by the system’s cruelties. It all culminates in one of the bleakest finales of a genre renowned for its grim, disturbingly open-ended conclusions. Moseby, left to impotently watch a man die, finally reintegrates into the land of the living, only to be ejected from it with greater force than ever through sheer trauma. Cole

Blade Runner (1982)

The dying Earth of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? reeks of pathos, dust, and decay, but it seems functional—beset by entropy, but functional all the same. The grunge and rot of Ridley Scott’s masterpiece, by contrast, owes a sizable debt to the legacies of film noir and steampunk: a future defined by overdevelopment, under-regulation, hubris, and greed. The film is fueled by iconography: icons that don’t always need to point outside the text, but half a self-sustaining power of their own. That’s why Roy (Rutger Hauer) is the titanic antihero, whose sheer magnitude as a synthetic being embarrasses the ineffectual Deckard (Harrison Ford), the ex-flatfoot whose character arc is a slender thread of fuck-ups and accidental victories. Nearly a minor character in the book, almost on the level of some expendable Dragnet hoodlum, Roy is transformed into the film’s evil superhuman, a universal adaptor capable of being fixed with any major philosophical lens (Nietzsche, Kant, Descartes, etc.). I tear up when I read certain passages in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?; I can’t say the same for Blade Runner. Then again, no one mourns in the film, except in a stolen moment (when Roy discovers Daryl Hannah’s defeated Pris), and Scott uses a reliable surrogate for tears to pay respects, on our behalf, when Roy’s spirit finally takes flight. Tears in the rain, indeed. Christley

JxSxPx's rating:

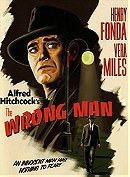

The Wrong Man (1956)

The Wrong Man finds Alfred Hitchcock far enough removed from his P.T. Barnum impulses that one could be forgiven for thinking its somber gravity represented his first stab at docudrama. In any case, it’s a woefully underrated and truly harrowing study of the psychological cost of misguided suspicion and mistaken identity. Hitchcock’s shadowy mise-en-scène is given a greater sense of veracity through his use of actual NYC locations and simple, almost workmanlike camera compositions (at its most effective, the film plays like the best episodes the Master of Suspence directed for Alfred Hitchcock Presents, only in excruciatingly brutal slow motion), and the narrative structure gains considerable urgency through the decision to begin the storyline almost immediately preceding Manny Balestrero’s (Henry Fonda) arrest. The audience is kept at a slight distance from the protagonist and, like his wife Rose (Vera Miles), is forced to take innocence at his word. And when Rose’s mind begins to unravel under the pressure of her own culpability in his alleged crimes (unlike many other Hitchcock characters, the real-life figure of Rose shoulders the guilt without any qualm), the sense of moral responsibility in Hitchcock’s films may have never felt more imperative and succinct. Henderson

JxSxPx's rating:

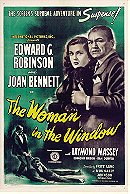

The Woman in the Window (1944)

In both his German and American productions, Lang’s characters wrestle with impulses that are at odds with prevailing social standards. Similarly, Lang, an architect of film noir, had to learn how to tame his massive and politically dangerous visions for America, which isn’t as uncomfortable with anti-fascist sentiments as it should be. Lang understands the suppression that’s casual in American life, even for the privileged men who’ve benefitted most from the American contract, such as Professor Richard Wanley (Edward G. Robinson), the protagonist of Lang’s gripping and subtly devastating The Woman in the Window. Notions of suppression and control serve as the film’s text, rather than as subtext. In the first scene, Wanley lectures a class on how the law has variously interpreted murder so as to represent the ambiguity of an act that can be committed for many reasons. Pointedly, Wanley notes that killing for gain and out of self-defense are markedly different, inadvertently foreshadowing the predicament that he will soon face. The Woman in the Window and Scarlet Street share many fascinating similarities, operating as parallels as well as inverses of one another, but Robinson’s respective performances are subtly differentiated. Wanley’s bitterness is laundered, passed off by the man as a kind of dignified resignation, which Robinson plays with a poignant musicality. He’s integral to the success of the film as an early and intricate deconstruction of the biases driving film noir. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Gilda (1946)

Charles Vidor’s Gilda places its eponymous bombshell between two men—both sexually frustrated, both concealing their impotence through deviant business practice—and has them not actually care too much about her beyond her value as a trophy to shield their perpetually fractured egos. The film questions the honesty of each character’s intentions by consistently revealing their interests to be wholly self-serving. Gilda is best appreciated as an intelligent back and forth on the fantasy of possessing another. Perhaps the film’s perspective on the battle of the sexes can be best summarized by Detective Maurice Obregon (Joseph Calleia), who introduces himself by commenting that “women can be extremely annoying.” Much later, when offering advice to Johnny Farrell (Glenn Ford) following an arrest, he ponders: “How dumb can a man be?” It’s the contingency of these statements that fascinates, because the film rightly recognizes that every character is capable of numerous actions that would qualify as “annoying” or “dumb,” but also that annoyance, on Gilda’s (Rita Hayworth) part, lies in the eye of the beholder. In the world of Gilda, and the greater spectrum of noir, it’s always about who’s watching. Dillard

JxSxPx's rating:

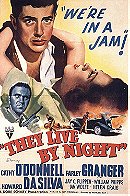

Nicolas Ray’s They Live By Night is a genre flick featuring only the bare minimum of generic trappings. It favors the quiet dramas of decision-making and one-on-one commiseration to the louder spectacles that occur, often unseen, to push the plot along. The dismal conditions surrounding Bowie (Farley Granger) and Keechie’s (Cathy O’Donnell) affair, while exposing the flaws in the institution of marriage, never impede the prospect of love, and Ray dedicates much screen time to episodes of whispery tenderness at the expense of any titillating criminal subplots. Indeed, often the only reminders of the parties trailing our hero are oblique in nature, as in the scene when the rumble of a passing train outside gets mistaken by Bowie as the sound of encroaching authorities. Paranoia briefly sets in, but Ray takes an unexpected route by inching his camera closer and closer to his characters’ faces as their affections strengthen in the face of sure disaster. (The film, then, isn’t a traditional, moralistic noir that fixates on the deterioration of a romance as a result of criminal associations.) The ostensible conflict dissipates to reveal the existential condition underneath: Sustained happiness is an impossibility in a world determined to commodify everyone and everything. Lund

JxSxPx's rating:

The Reckless Moment (1949)

Between her collaborations with Fritz Lang and role in Max Ophüls’s The Reckless Moment, Joan Bennett is surely the grande dame of noir. In Ophüls’s film, though, Bennet doesn’t play the role of the femme fatale, but a strong-willed mother struggling to maintain the seeming normalcy of her middle-class existence. Blackmail, murder, and dangerous gangsters all rear their ugly heads after Bennett’s Lucia, taking her role as protector of the family to irrational heights, disposes the body of her teenage daughter’s criminal lover. And yet despite the potential terror and violence bearing down on her, Lucia still manages to pay the bills and make it home in time for dinner. Existential dread is exhausting business, however, as is apparent in the brilliant sequence of Lucia lugging a corpse through a beach and onto a boat in order subsequently dump the body in the water. Throughout, Bennett imbues Lucia with a chilling stoicism within Ophüls’s shadowy long takes, making this most demanding of roles seem almost easy. Greene

Daisy Kenyon (1947)

Otto Preminger’s Daisy Kenyon is a troubling and ambiguous portrayal of three real, unknowable characters (and actors) in constant flux, which means constant danger, both emotional and physical. “There’s nothing like a crisis to show what’s really inside people,” says Daisy (Joan Crawford), a tense, willful woman unhappily involved in an affair with a married man, attorney Dan O’Mara (Dana Andrews). Actually, Preminger’s film proves through patient, almost medical analysis that people are even more difficult to figure out when they get pushed to their limits. Preminger delights in scrutinizing the often inscrutable masks of his three lead actors, gliding his camera like a panther in and out of their lonely, studio-set darkened spaces. The film, which was generally dismissed as a slick triangle melodrama, has emerged as one of the most adult of all post-war noirs, filled to the brim with subsidiary characters who seem to have their own life and cares. If you want to see what a major director can do with standard material, just watch the way Preminger handles a late restaurant confrontation between the participants of his queasy love triangle, alternating close-ups and off-kilter framing until the tension reaches such a boil that it starts to burn away everything but the salient, courtroom-like facts of the matter. Soap opera is distilled to its real-life essence, until what’s left is nothing less than the ultimate mystery of art. Dan Callahan

Night and the City (1950)

In Jules Dassin’s unorthodox noir Night and the City, Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark) is a snipe without a career plan, an “artist without an art,” as one character states early on, whose hustling of tourists and quick-cash schemes result in widespread disdain at even a mention of the character’s name, most notably among his former business partner (Francis L. Sullivan) and sometime lover (Gene Tierney). Dassin is interested in Fabian as an idea, as a point of contention for contemplating the stakes of business ethics. After all, Fabian isn’t a boy, but not yet a man, who’s likely to be reviled by those too quick to pass judgment, neglecting to see that Fabian’s struggle is real and one derived from his refusal to accept the terms of a law-abiding cash flow. He’s a crook, to be sure, but determining what kind of crook is the driving force behind the film, which is fraught with perilous tensions regarding personal wealth and communal well-being and ultimately serves as a companion piece to the equally irreverent Thieves’ Highway. Dassin affords Fabian the space to witness his own crashing and burning, which lends Night and the City a sweetly noxious air, where failings of desire lead to an inevitable end of violent restitution, carving out the cancerous, societal cell. That’s what everyone comes to view Fabian as: a worm, a lesion, a spot to be removed. Nevertheless, one would be wholly remiss to categorize Dassin’s film as taking the same stance, since there’s a perpetual empathy afforded to Fabian, often in close-up, with Widmark’s trademark grin and eyes, reeking of freshly minted desperation, caked upon years of slimy, two-bit behavior. Dillard

JxSxPx's rating:

Ace in the Hole (1951)

In Chuck Tatum (Kirk Douglas), Ace in the Hole synonymizes interpersonal nastiness with an American’s ultimate right to do whatever the hell he or she wants, because whatever most anyone wants will almost certainly be bad for themselves and everyone else. That’s the great American riddle of freedom that Wilder’s unpacking. Wilder thrusts you headfirst into a frenzy of parasitic activity. You wait for a respite from the debauchery, for a character who testifies just a little to life’s potential for decency or at least mercy, and Wilder, aware that you’re awaiting such reassurance, toys with you again and again. Even the film’s sacrificial lamb, Leo Mimosa (Richard Benedict), is morally tainted, as he’s stuck in a mine cave-in because he was looting Native American artifacts. That’s not illegal, it’s Richard’s family’s land, but this action only reaffirms Wilder’s worldview of society as a series of negotiations pertaining to gradations of violation, whether personal or business. In several gorgeous and despairing master shots taken from Tatum’s point of view as he surveys his kingdom from atop a mountain perch, the carnival, with its corrupt law officials, firemen, lonely wives, school children, and even a restaurant, suggests a boom town at the dawn of the gold rush. In this extremis, the country’s political and social machinations are peeled of elaborations and subtleties to reveal one gloriously intricate long con that started with our fleecing of the Native Americans’ land (a recurring subtext) and pushes on with our fooling ourselves with a media system that we use primarily to sate our greed and ghoulish curiosities. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Carol Reed’s Odd Man Out is a character study wrapped in the guise of a sociopolitical thriller, and a work which accordingly plays better when accentuating the moral and personal complexities of the former through the aesthetic prism of the latter, shedding the weight of topical investment even as the shadows of its influence hang literally and figuratively on the film’s dramatic landscape. As in The Third Man, which was also rooted in the feel of poetic realism and the look of German Expressionism, much of Odd Man Out is given over to conversations about an off-screen character—in this case Johnny (James Mason), a radical insurgent on the lam in Belfast—who nonetheless propels the action through his own non-action. In lieu of a traditional protagonist, supporting characters are tasked with preserving the story’s intrigue. These include a sympathetic priest (W.G. Fay), a steely eyed police officer (Denis O’Dea), a down-on-his-luck local (F.J. McCormick), and an opportunistic artist (Robert Newton)—idiosyncratic figures granted individual episodes with narrative consequence ranging from purely functional to genuinely stirring. The film’s through line, however, is Johnny and Kathleen’s (Kathleen Ryan) doomed romance, wrested from their grip only to be reclaimed and, ultimately, sealed by their own hands. It’s a bleak, suitably intimate conclusion to a film which from its opening proclamation portends something expressly visceral. Cronk

In Lost Highway, the anxious justification of a Hollywood Hills homeowner to a police investigator when asked why he prefers not to keep personal records—“I like to remember things my own way. How I remembered them, not necessarily the way they happened”—might as well be David Lynch’s artistic mission statement as far as his relationship to noir is concerned. Structured as two discrete Los Angeles narratives sutured together at the film’s midpoint by sheer force of will, Lynch’s most sinister moebius strip spills the genre’s bare ingredients from its maker’s id in disconnected fashion, leaving the audience to sort through distorted archetypes, mystifying red herrings, and suggestive doublings without any of the usual causalities and linearities we expect from narrative filmmaking. First hypnotizing us with the story of Fred and Renee Madison (Bill Pullman and Patricia Arquette), a married couple haunted by a series of inexplicably invasive videotapes left on their doorstep, the film then leaps to an alternate timeline (or is it dimension?) after a traumatizing act of violence occurs. Suddenly, we’re following newly released death-row inmate Pete Dayton (Balthazar Getty) as he readjusts to his suburban life and auto-mechanic gig while finding himself unable to escape the odd pull of a mobster friend’s blond bombshell of a mistress (also played by Arquette). Often analyzed as an experiential depiction of the rare phenomenon of psychogenic fugue, the film is best appreciated as an ever-unfurling nightmare in which the only thing worse than the stygian terrors on screen is the numbing reality one has to wake up to. Carson Lund

With its too-cool-for-school bevy of film and literary references, Jean-Luc Godard’s masterpiece both foresaw and helped to launch the now-dominant notion of pop-culture obsession as badge of honor. We may smile at Jean-Paul Belmondo’s rapt idolization of Humphrey Bogart, for instance, but it’s more knowing grin than disconnected smirk. Then there’s the ooh-la-la chic of Raoul Cotard’s black-and-white cinematography; the simmering yet self-aware dance of seduction enacted with such arch grace by Belmondo and Jean Seberg; the casual fatalism that never seems to go out of style, especially when spoken in French and accompanied by swirls of cigarette smoke. What remains most striking, and most moving, about Breathless is its sophisticated yet largely guileless faith in the filmic medium, a cinephilia untainted by smugness or cynicism. Of course, such affection did not stop Godard from throwing out a slew of established filmmaking rules, from the continuity editing system to the notion that a film had to be inhabited by psychologically-consistent “characters” acting out a linear, cause-and-effect “plot.” But watching Breathless, one never gets the sense that Godard breaks these conventions out of anger or disgust—at least not yet. It comes from a place of jittery excitement and possibility, the double vision of appreciating so deeply the riches of cinema’s past and seeing so vividly what shape its future could take. Matthew Connolly

You Only Live Once (1937)

“Oh kid, the bottom’s dropped out of everything,” says three-time loser Eddie (Henry Fonda) to his devoted wife, Joan (Sylvia Sidney), after realizing he’s been framed for murder. Eddie’s tried to fly the straight and narrow since his last trip to the clink, but everyone besides Joan sees only a two-bit crook. The world in Fritz Lang’s mesmerizingly bleak You Only Live Once is a cold and unforgiving place for an ex-con. Indeed, Eddie can’t catch a break, as he’s booted from a hotel in the middle of the night and then canned from his job, all because it’s impossible for him to shake the stink of having been inside prison. Now he’s stuck with a bill that can only be paid by the electric chair. When the truth is finally revealed, by a priest shrouded in shadow, it’s dimmed by so much hysteria. For Eddie, freedom exists only once he hits the open road, an outlaw on the run from the very system that put him in a vice grip and forced him back into the criminal world. Smith

“Startlingly vulnerable” is Mulholland Drive in a nutshell. It suggests that Lynch got a little high on the un-ironic emotionalism of his wonderful The Straight Story, fusing it with a narrative that refines the malleable identity/reality crises that fueled Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me and Lost Highway. All of Mulholland Drive’s digressions are proven to narratively matter; a high degree of control is revealed to exist underneath a misleading aura of chaos. Adam Kesher’s temporary downfall, Camilla Rhodes’s career ascension, the pointed introduction of a Winkie’s waitress, Diane—these are major details disguised as minor ones. The “major” thread, a Sirkian amnesia mystery investigated by junior sleuths Rita (Laura Elena Harring) and Betty (Naomi Watts), is proven to be a form of distraction, a fantasy born from a death rattle. Winkie’s is haunted by a monster because something terrible and pitifully simple was brokered there. Betty’s potential stardom is really Camilla’s, though it takes us a while to meet the real Camilla. But, like the film’s other realities, she’s been right in front of us all along. Bowen

JxSxPx's rating:

Underworld, U.S.A. (1961)

Samuel Fuller had a way of injecting, like steroids, a fatalistic energy into his films. The technical storytelling techniques employed in Underworld U.S.A. are some of the most unorthodox in classic American film; we repeatedly cross-cut between very different sets without any establishing shots to cushion the transition, and the camera nimbly trucks, crablike, across rooms to reveal major plot points without fanfare. The effect is disorienting—nearly inebriating—but it also in a way explains, or perhaps prepares us for, the odd, platonic betrayals that Fuller is obsessed with depicting. Every time we zoom into the pitch-black belly of a safe cracked open by the delinquent Tolly (Cliff Robertson), we’re enveloped by the dark interpretation of patriarchal loyalty the man must uphold by avenging his father’s death at the hands of powerful mobsters. Intentions—rather than actions, or Darwinian will—rule Fuller’s world, which might also be why his espirit remains an acquired taste: Intentions aren’t visceral enough to be instantly accessible. It’s not the editor’s violence that dooms him in Scandal Sheet but his hubris, and his aggrandizing desire to become the headline while eluding the unforgiving judgment of the printed page. And it’s Tolly’s cloud of feigned ignorance over the particulars of his daddy’s death in Underworld U.S.A. that allow his self-destructive intentions to flower so splendiferously—and to keep us violently cycling reactions of repudiation and identification toward the screen. Lanthier

Taxi Driver (1976)

In the same way that World War II is the unspoken backdrop to the hypermasculine, existential angst of the original noir cycle, so is the Vietnam War the repressed original trauma of Travis Bickle (Robert De Niro), the brainchild of screenwriter Paul Schrader. Bickle takes it upon himself to fix what he sees as a corrupt, fallen society, avenging the lost innocence embodied in an underage prostitute played by a young Jodie Foster. The ambivalence of Taxi Driver’s politics comes from the uncertainty of its emphasis: Is it on the notion of a morally sick modernity as embodied in Foster’s character, or on the cycle of violence perpetuated by the modern fascist who adopts the mantle of traditionalism? Much in the film points toward the latter, but the confessional mode of Martin Scorsese’s storytelling colors the story with the director’s fraught and rather conservative concern about the impossibility of a traditional moral order in the modern world. Brown

JxSxPx's rating:

High and Low (1963)

Akira Kurosawa’s classic ronin heroes brandished samurai swords and long bows to achieve victory over their evil foes. The conflicted modern-day professionals populating his masterful crime drama High and Low don’t have the luxury of such black-and-white confrontations. These men live in a complex world ripe with ideological contradiction and corporate greed, a suffocating post-war landscape split apart by social unease. Whether it’s the tortured businessman Gondo (Toshirô Mifune), the focused Inspector Tokura (Tatsuya Nakadai) and his squadron of dedicated police, or the brutal kidnapper (Tsutomu Yamazaki) hounding them both, each finds absolution in the way of the pen, paper, or gun. In turn, investigatory process and rational thought become Kurosawa’s new duels for supremacy, stretching what initially seems like a straightforward procedural to the level of Shakespearean tragedy. Heath

Murder by Contract (1958)

Limpid, compact low-budget ingenuity. Emotionless hepcat Claude (Vince Edwards) insinuates himself as a contract killer for an unseen Mr. Big and, after proving his efficiency with a couple of clean rubouts, gets handed a major assignment—offing a mob witness holed up behind a wall of feds. Closer to Paul Schrader’s narcissistic loners than to Jean-Pierre Melville’s spiritual sangfroid, Edward’s chilly sheen is stuffed with pocketbook fatalism, but Murder by Contract’s cunning oddness levels its pretensions. Irving Lerner’s camera records Claude’s moral emptiness with a sharpshooter’s calm—all the better to place his blankness against the jitters of Herschel Bernardi’s George and Phillip Pine’s Marc, the Mutt n’ Jeff hoods chaperoning him. Croce

JxSxPx's rating:

The Killing (1956)

Stanley Kubrick’s masterful manipulation of chronology brings an excruciating sense of doom to The Killing, a classical noir about a carefully threaded heist unraveled by the scheming of a fiendish femme. Having already emasculated her lapdog husband, Marie Windsor’s psychosexual dominatrix Sherry Peatty gets covetous upon catching wind of granite-faced Johnny Clay’s (Sterling Hayden) race-track robbery plot, which requires an eclectic assortment of participants (insane rifleman, wimpy clerk, crooked cop, kind bartender, chess-playing wrestler) and which is orchestrated—save for Windsor’s anomalously hot-blooded scenes—with the icy auteur’s trademark precision and attention to detail. Proficiently splicing and reshuffling the action until it seems that only fate (or the ever-godlike director) is fully in control of Hayden and his crew’s destinies, Kubrick generates portentous suspense via discordant staging and methodical camera calisthenics until, faced with inescapable failure, Hayden’s thug can barely muster the energy to utter, “Eh, what’s the difference.” Schager

JxSxPx's rating:

The Narrow Margin (1952)

As lean and muscular as its portly train passenger is obese (“Nobody loves a fat man except his grocer and tailor”), Richard Fleischer’s The Narrow Margin delivers crisp crime drama interested in challenging assumptions about identity. Charles McGraw’s Det. Sgt. Walter Brown escorts a mobster’s wife, Frankie Neall (Marie Windsor), to L.A. via locomotive so she can testify. Evading on-board killers and coping with sunshiny Ann Sinclair (Jacqueline White) and her pesky kid, however, is nothing compared to the cop’s confounding attempts to decipher who’s who. Poised shifts in focus, disorienting cuts, and animated lighting bestow the surprise-filled story with concussive vigor, while Windsor’s pitiless broad gives it its dark sensuality. Schager

Moonrise (1948)

Frank Borzage’s Moonrise is a sensual scrutiny of a man’s free will. In the film’s striking opening moments, a dazzling spectacle of black-and-white chiaroscuro conveys the throbbing sense of madness that’s cattle-branded into the imagination of Danny Hawkins, who’s terrorized by bullies from childhood to adulthood because of his father’s execution. When Danny (Dane Clark) kills one of his tormentors, he must struggle with the terrible push-pull effect of the past and the memory of his father on his psyche. Borzage magnificently frames the film along very severe, richly layered diagonal angles, catching nervous hands and faces from odd positions and giving startling visual expression to Danny’s loose grip on his moral compass. A shot might begin with Danny towering above a character, only to end with him cowering beneath the same person, and in a tour-de-force sequence at a town fair, Borzage’s camera moves in heady and terrifying tandem with the stop-go movements of a Ferris wheel. The director plays with shifting perspectives to convey the disorientation of a man struggling to stay on top even as he’s drowning. Gonzalez

JxSxPx's rating:

Point Blank (1967)

Influenced by the French New Wave’s radical formal innovations, the ennui of Michelangelo Antonioni’s films, and the genre revisionism of Sergio Leone’s spaghetti westerns, John Boorman set out to make a thriller that looked and felt like nothing else before it, using widescreen Panavision cinematography, explosive colors, and a multi-layered soundtrack to re-envision the noir picture as highbrow Euro-art film. Whereas noirs generally boast a shadowy, expressionistic interplay between light and dark, Boorman casts most of his film in brilliant daylight and summery colors. Where noir creates a visual and thematic atmosphere of constriction and imprisonment, Boorman shoots everything in expansive widescreen that posits characters in oppressively open spaces and, when more than one person is on screen, at opposite ends of the frame. And instead of noir’s typically convoluted narratives involving plenty of unnecessary exposition, Point Blank is a model of silent visual storytelling that broke new ground in non-linear cinematic narrative construction. Schager

JxSxPx's rating:

Force of Evil (1948)

The climax in many a John Garfield-starring noir hinges upon a violent realization, as opposed to simply hinging upon violence. This crescendo arrives in Abraham Polonsky’s Force of Evil when Joe Morse (Garfield), a reptilian lawyer who tries to gain control of New York City’s numbers racket, discovers that his phone’s been tapped. He picks up the handle with slowness, to compensate for his overactive mind, and hears the dial tone’s smoothness disrupted with a nonchalant click—the wire-tapper’s residue. The screen cuts to Morse’s sweaty eyes in close-up; terror has emptied them not only of all emotion, but all thought. The film manages reversals in tone almost entirely through photographic rather than textual or aural means; its rather clever use of clicks in the sound design notwithstanding, the moral cadence is purely visual, as with superlative crime movies from the silent era. Consider, for example, the dark-washed final set piece, which occurs in lightless offices that have up until then been professionally sunny, despite the shadowy law-bending that took place within them. And the epilogue, wherein Morse hunts for a crucial piece of evidence under the Washington Bridge, exposes him, finally, to the pellucid and unconquerable immensity of New York City’s skyline (unseen since the main titles). This shakes loose the chamber film mustiness from Force of Evil while subjecting Morse’s ambitions to one last dwarfing. Morse loses, but New York wins. Lanthier

JxSxPx's rating:

In Femme Fatale, Laure Ash (Rebecca Romijn-Stamos) packs a gun and a one-liner or two, challenging the way men perceive women and using that awareness to devour and spit out her men. Brian De Palma performs a triple whammy when he superimposes Romijn-Stamos’s face over that of the film’s many women (Barbara Stanwyck during the film’s opening shot and John Everett Millais’s Ophelia when Laure chit chats with Anonio Banderas’s Nicolas Bardo over cold espresso): He acknowledges the character’s split self, reinforces the dreamlike impulsion of the narrative, and provides the sexist noir tropes of the past with another affront. De Palma’s formal fixation with dualities is so pervasive that the film takes on the texture of something to be deciphered—like a puzzle. (Always there’s a sense of the past looking forward into the present, and that any given move can forever change the shape of all things.) Even the dash that separates “East” from “West” in the title of Regis Wargnier’s hideous East/West, the film enjoying its gala premiere during Femme Fatale’s Cannes Film Festival-set opening sequence, suggests a crisis, one between two very different worlds of thinking—and making movies. Gonzalez

Act of Violence (1949)

Fred Zinnemann’s lean, mean Act of Violence opens at night on a man hurriedly limping into a rundown building and up a dimly lit stairway. He fumbles through some clothes in a drawer for a few seconds before pulling out a pistol and cocking it with a look of both anguish and excitement on his face. The man, Joe (Robert Ryan), hops on a bus to California to pay a visit to a fellow POW, Frank (Van Heflin), who now enjoys his newfound status of war hero in his little slice of suburban heaven. Frank may be done with the past, but Joe isn’t coming there to trade war stories. He’s got a bullet with Frank’s name on it, a special delivery for a cowardly act of betrayal that everyone but Joe has forgotten about; he’s still got that limp to remind him every step he takes. The men are two sides of the same coin, the fractured identity of the post-war American male: the id, driven by a thirst for justice and revenge, and the superego, willfully repressing the horrific violence of the recent past, trying to blend seamlessly into America’s post-war makeover. But a new war is about to start and a white picket fence isn’t much of a defense. Smith

Load more items (50 more in this list)

People who voted for this also voted for

A24

Phoenix Feather's Childhood Favourites

Top Movie Road Trip and Car Songs

Once Upon a... List

Covid-19 Stay at Home Plan to watch

Favorite New Wave/Electronic Songs: Vol. 2

Villains of the ghibli studio

Mid-Year Oscars Predictions - 2020 Movies

Favorite Drama Films: 1988-1989

Favorite Female Characters/Performance of 2019

1997 Films ranked

1978 Films Ranked

1973 Films Ranked

Favorite Drama Films: 1986-1987

Road Trip Movie List Collection

More lists from JxSxPx

TCM's Essentials: 52 Must See Movies

Slant's 100 Best Sci-Fi Movies of All Time

TCM’s The Essential Directors

The B List

TCM’s Essentials Vol 2: Another 52 Must See Movies

100 Greatest American Albums of All Time

TCM’s 50 Must-See Musicals

Login

Login

375

375

8.1

8.1

7.9

7.9