In Praise of Yasujiro Ozu

Sort by:

Showing 10 items

Rating:

List Type:

"It is through this elegant quietness that Ozu navigates his slight stories around the expected landmarks of dramatic curves and heightened emotions. Nothing is forced. All that is left on screen are the smallest details of human nature and interaction, delivered through a lens that is delicate, observational, reductive, and pure."

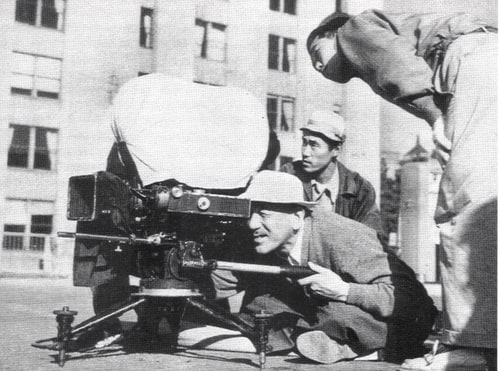

“If there were still sanctuaries in our century… if there was something like a holy treasure of cinema, for me, that would be the work of Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu. He made 54 films. Silent movies in the 1920s, black and white films in the 1930s and 1940s and finally color films until his death on the 12th December 1963, on his 60th birthday.

Although these films are distinctly Japanese, they are also global. In them I recognized all families, in all the countries in the world, as well as my own parents, my brother and myself. Never before and never again was film so close to its essence and its purpose. Showing an image of the human in our century. A useable, true and valid image, one in which he cannot only see himself but rather learn something about himself.

Ozu’s work doesn’t need my appraisal. And such a “holy treasure of cinema” is just imaginary. So my journey to Tokyo was no pilgrimage. I was curious to see if I could discover something from this time, whether something was left of his work, images perhaps, or people even… Or if in the 20 years since Ozu’s death so much changed in Tokyo that there was nothing left to be found."

Ozu’s grave bears no name—just the character mu, meaning ‘nothingness.’

“It is a grave of a filmmaker who for me, and I can only speak subjectively elevated film, the artform of the 20th century to it’s most beautiful form, one that cannot be imitated or repeated.”

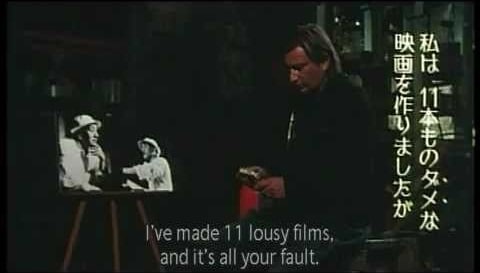

"Ozu-san. *bows* I’m Aki Kaurismäki from Finland. I’ve made eleven lousy films, and it’s all your fault."

"In London in 1976, my brother forced me to visit the Film Institute, where I saw Tokyo Story. After that, I gave up my dreams about literature. I decided to begin my search for a red kettle."

"What I respect most is that Ozu never needed to use murder or violence to tell everything that's essential about human life."

"So far I've made 11 lousy films, and I've decided to make another 30, because I refuse to go to my grave, until I have proved to myself that I'll never reach your level, Mr Ozu."

"I chose this old factory for shooting because I have a tendency to look to the past. I'm not a person who presses forward with confidence in the future and in technology. I prefer to look back. I think Ozu was like that too during his time in Japan."

"The epitaph on my grave will be 'I Was Born, But...', Arigato."

“The first time I wrote about Ozu was 1957 I wrote a piece about Tokyo Story for Sight and Sound publication called “2 Inches Off the Ground.” I’ll explain that title—Alan Watts, an English writer, once said when DT Suzuki was once asked how it feels to have satori, the zen experience of awakening, he replied: ‘Just like an ordinary everyday experience, except about 2 inches off the ground.’

“So I called the piece I wrote “2 Inches Off the Ground” because that was the effect which Tokyo Story had on many people in the UK and now regarded all over the world as a masterpiece. Tokyo Story was made by someone who understood what life was like in a family or things that affect us all.

“It’s often thought that films get out-of-date or old-fashioned. I don’t really think they do, particularly films that are made in the classic and absolutely straight forward spirit of Mr. Ozu. He had a great understanding and that understanding is still present in his films and it’s an understanding of the life we all have to lead with an honesty that is constant and also a kind of irony that gives them the right kind of humor, without ever being sarcastic that’s why I think Ozu survives and his work survives as the work of one of the great directors of the cinema.”

“I think Ozu is like a mathematician. He knew the lives of Japanese people very well. It's as if he analyzed them in a detailed way, that’s why I call him a mathematician.”

(First image is a shot from Dust in the Wind (1986) in which the character is facing the screen when talking. A clear nod to Ozu's signature compositional device.)

On the best film ever made:

"That’s Tokyo Story by Ozu. In my life Ozu’s Tokyo Story is always the number one."

"I love Ozu's movies, because they speak of the family, of the role of women within the family. They remind me of my own story."

"Ozu was a filmmaker who treated mostly the family. All his films are centered on family relationships: father-son relationship, mother-daughter, father-daughter, etc. His camera seems to never leave the family cocoon. As someone who has spent his life filming the same subject, he must have had a great passion for this topic. He could not go away from it. Of course, my own experience made me quickly recognize myself in his movies."

"While preparing my documentary Yang + / -Ying (1996), I had the opportunity to meet with Hou Hsiao Hsien, who's a great admirer of Ozu too [Hou Hsiao Hsien paid tribute to Ozu with his movie Café Lumière, 2004.] .So we discussed about our passion for this director. We concluded that a good film should be able to translate this idea, which can be said in eight words (or eight characters in Chinese): "Being close with distance, being remote without forgetting. "[ 'Ji jin as yuan, yuan ji jin that"]. Whether Ozu, Hou Hsiao Hsien, or any other great director, I think all this appears clearly in their works. A good director must know how to convey to the public his passion for a given theme, while maintaining a certain distance with his subject. One should not run into the topic. You must be able to get away from time to time, and return at the right time. The distance is necessary if we want to convey the message."

"I love Ozu because I found in him constancy in themes and in style which both speak to me."

Tokyo Story also reminded him of an old Chinese proverb:

“The wind never lets trees rest calmly. Observe filial piety.”

“I had heard a lot about Ozu from American and French friends and I have a bit of a distaste for worshiping any particular film director. I didn’t rush out to see Ozu’s films. Then a cinema in the Latin Quarter held a retrospective of Ozu’s films. By chance I wandered in and saw Autumn Afternoon. I know that the film had spoken to me and addressed me in a way that had nothing to do with being a film buff.”

On Ozu's influence in 35 Shots of Rum: “He was the blueprint for this film.”

"To love movies without loving Ozu is an impossibility."

"Ozu developed a visual style that was unlike anybody else's. Although in some of the silent films at Facets you can see that he obviously studied Hollywood directors, he had certain visual trademarks that were all his own."

“Besides affecting me a lot personally what Ozu did for me and a number of other filmmakers my age showed a way film could operate and affect you which was not the normal kinetic energetic way of cinema. It was a much quieter and more interesting way of cinema.”

"The Japanese say no director is more Japanese than Ozu. And they're right. He is indeed profoundly Japanese. But when you talk about being profoundly American, or Japanese, or British, when you dig down really deep, it's all universal. That's why we are so moved by films like Tokyo Story and Late Spring and Early Summer - because we truly understand what the characters are going through, and we recognise their humanity. Deep down, we share our essential humanness. We feel the same things. Intellectually we may be different, but emotionally we're very much the same."

Passages from his book "Ozu: His Life and Films":

"The viewer of an Ozu film is expected to infer the characters’ feelings, and usually the dialogue is so beautifully written that reasonably attentive viewers do just that, whether consciously or not. … … in the films of Bresson and the earlier pictures of Antonioni, though, thoughts and feelings are so lightly implied that we must infer most of the motivation. The same is true of the Ozu films; as in the middle novels of Henry James, we are shown everything and told nothing.“

“Loneliness and death are in a sense such banal facts of human experience that only a great artist, a Tolstoy, a Dickens, an Ozu, can restore to them something of the urgency and sadness that we all someday experience … … Ozu is one of the very few artists whose characters are aware of the great immutable laws that govern their lives.”

Ozu has ensured that we sense something larger than the emotion we are both seeing and feeling, that at the same time we become aware of the universality of all emotion — in short that we feel something of the texture of life itself and again know that we are part of this universal fabric. Empathy is thus transformed into an appreciation, and experience into personal expression.”

All aspects of an Ozu film, then, dialogue, scene, sequence, sound, were patterned; they were module-like units … … One reason Ozu can successfully impose such a pattern upon his material, can do so, that is, without falsifying, is that the sequence pattern is not the story pattern … … The higher authority in Ozu’s picture is the unvarying structure of the film itself, and not, as in most films, story or plot.”

Yasujirō Ozu (小津 安二郎, Ozu Yasujirō, 12 December 1903 – 12 December 1963) was a Japanese film director and screenwriter. He began his career during the era of silent films, and his last films were made in colour in the early 1960s. Ozu first made a number of short comedies, before turning to more serious themes in the 1930s. The most prominent themes of Ozu's work are marriage and family, especially the relationships between generations. His most widely beloved films include Late Spring (1949), Tokyo Story (1953), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962).

Widely regarded as one of the world's greatest and most influential filmmakers, Ozu's work has continued to receive acclaim since his death. In the 2012 Sight & Sound poll, Ozu's Tokyo Story was voted the third-greatest film of all time by critics world-wide. In the same poll, Tokyo Story was voted the greatest film of all time by 358 directors and film-makers world-wide.

Ozu: "Rather than tell a superficial story, I wanted to go deeper, to show the hidden undercurrents, the ever-changing uncertainties of life. So instead of constantly pushing dramatic action to the fore, I left empty spaces, so viewers could have a pleasant aftertaste to savor."

Added to

22 votes

To Watch II - Film Lists

(152 lists)list by PulpRoman

Published 6 years, 2 months ago  2 comments

2 comments

2 comments

2 commentsPeople who voted for this also voted for

Film Diary of 2023

Ballet Dancer Postcards - Ballerina

Mabel Normand - Faces of Charlie Chaplin

Cigarette Cards: British Trees (1927)

My Favorite Albums - 1998

Listened to in 2020: Albums

Australian Films

Artwork by Joe Jusko

Listened to in 2024: Albums

TV Posters I Posted ~ 3+ Votes

2014 Films Ranked

The Best In Literature For Me.

actors who regularly starred in giallo films

Charles Sheldon Photographs (2)

Daibutsu、Giant Buddha of Japan

More lists from shotswerefired

Rewatched (2023)

Danny Chan's Greatest Hits

Press-Up Junkies

AMWF Relationships in Cinema and TV

In Praise of Muhammad Ali

Behind Every Successful Man Stands A Mother

Films Due A Quality Blu-ray Transfer

Login

Login

8.2

8.2

0

0