ALL-TIME 100 Revisited

Sort by:

Showing 20 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

TIME's critic, Richard Corliss, updates our All-TIME 100 list of the greatest films made since 1923 — the beginning of TIME — with 20 new entries

Movies

Performances

Guilty Pleasures

Novels

Graphic Novels

Albums

Movies

Performances

Guilty Pleasures

Novels

Graphic Novels

Albums

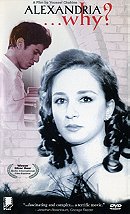

Alexandria... Why? (1980)

For decades, at film festivals, Egyptian director Youssef Chahine (1926–2008) was the prime representative of an entire continent, Africa, and a world religion, Islam — though his family was Christian and his ancestors came from Greece and Lebanon. Both a nationalist and an internationalist, Chahine loved Hollywood movies (as a young man he studied acting at the Pasadena Playhouse) and learned as much from their robust pace as he did from the gritty humanism of Italian neorealist films and the romantic sweep of Indian cinema in its postwar golden age.

Chahine’s near masterpiece Alexandria …Why?, the first of his Alexandria quartet of films, is set in Egypt during World War II, when Arab nationalists were killing English soldiers — anything to get the British empire out of Palestine. But this sprawling epic is mainly the story of a young man, transparently Chahine himself, who loves Shakespeare and American movies. At the end, he sails into New York Harbor as Glenn Miller’s “Moonlight Serenade” plays on the soundtrack. Below him are some Hasidic Jews; above is the Statue of Liberty, which has morphed into a heavyset actress he knew back home and is exploding in a ribald laugh. The collision of world cultures was rarely defined with such brio.

Chahine’s near masterpiece Alexandria …Why?, the first of his Alexandria quartet of films, is set in Egypt during World War II, when Arab nationalists were killing English soldiers — anything to get the British empire out of Palestine. But this sprawling epic is mainly the story of a young man, transparently Chahine himself, who loves Shakespeare and American movies. At the end, he sails into New York Harbor as Glenn Miller’s “Moonlight Serenade” plays on the soundtrack. Below him are some Hasidic Jews; above is the Statue of Liberty, which has morphed into a heavyset actress he knew back home and is exploding in a ribald laugh. The collision of world cultures was rarely defined with such brio.

JxSxPx's rating:

All About My Mother (1999)

The Spanish word for life ought to be Almodóvar. Since bursting onto the international film scene in 1980, this irrepressible showman has served up tangy, nourishing stews of bent men and brave women, of comedy and melodrama, passion and grief. His 1988 Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown made him a sensation in the States, but All About My Mother was the true breakthrough, touching a depth his early films only danced around.

Its heroine is Manuela (Cecilia Roth), a Madrid nurse who works in her hospital’s organ-transplant unit and has lovingly raised her darling son Esteban (Eloy Azorin). When he is tragically torn from her, she conceives a mission: to grieve heroically and heal the wounds of other desperate souls. Manuela is the ultimate organ donor: now that her heart has been broken, she gives pieces of it to everyone. In Barcelona, by chance or fate, she meets her flock: Sister Rosa (Penélope Cruz), a nun who deserves many fretful prayers, and her bitter mom (Rosa Maria Sarda); the stage actress Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes) and her druggie lover Nina (Candela Pena); and Agrado (Antonia San Juan), a transsexual prostitute. Manuela helps all these women fulfill their dreams on their way to transcendence, accommodation or early death. Almodóvar nearly topped himself with the 2002 Talk to Her, another buoyant film about mourning, which won a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. But Mother remains the most mature and satisfying work in a glittering, consistently surprising career.

Its heroine is Manuela (Cecilia Roth), a Madrid nurse who works in her hospital’s organ-transplant unit and has lovingly raised her darling son Esteban (Eloy Azorin). When he is tragically torn from her, she conceives a mission: to grieve heroically and heal the wounds of other desperate souls. Manuela is the ultimate organ donor: now that her heart has been broken, she gives pieces of it to everyone. In Barcelona, by chance or fate, she meets her flock: Sister Rosa (Penélope Cruz), a nun who deserves many fretful prayers, and her bitter mom (Rosa Maria Sarda); the stage actress Huma Rojo (Marisa Paredes) and her druggie lover Nina (Candela Pena); and Agrado (Antonia San Juan), a transsexual prostitute. Manuela helps all these women fulfill their dreams on their way to transcendence, accommodation or early death. Almodóvar nearly topped himself with the 2002 Talk to Her, another buoyant film about mourning, which won a Best Original Screenplay Oscar. But Mother remains the most mature and satisfying work in a glittering, consistently surprising career.

JxSxPx's rating:

Avatar (2009)

In the year 2154, a group of militant earthlings lands on the Alpha Centauri moon Pandora, planning to subjugate the locals and mine its sylvan depths for a precious mineral. Making his first fiction feature since the unsinkable blockbuster Titanic, James Cameron marshaled hundreds of artisans for a dream project and created the most vivid and convincing fantasy world seen in the history of moving pictures.

The romance of the American Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) and the 10-ft.-tall, blue-striped Neyfiri (Zoe Saldana), daughter of the Pandorans’ tribal chief, fits the contours of the Titanic romance — a grunt falls in love with a princess — but transmits far more emotive power. Instead of embracing on a ship’s prow, Sully and Neyfiri ride their banshee steeds in ecstatic communion across the faraway sky; think of them as the prince and princess of the world. The climactic battle is stage-managed for maximum thrills. But the supreme joy of Avatar is in its long central portion: a safari through the luscious landscape of Pandora. It’s an impossible but completely seductive world that invites the viewer’s total immersion in a state-of-the-art experience that for years to come will define what movies can achieve — not in duplicating our existence but in dreaming new ones.

The romance of the American Jake Sully (Sam Worthington) and the 10-ft.-tall, blue-striped Neyfiri (Zoe Saldana), daughter of the Pandorans’ tribal chief, fits the contours of the Titanic romance — a grunt falls in love with a princess — but transmits far more emotive power. Instead of embracing on a ship’s prow, Sully and Neyfiri ride their banshee steeds in ecstatic communion across the faraway sky; think of them as the prince and princess of the world. The climactic battle is stage-managed for maximum thrills. But the supreme joy of Avatar is in its long central portion: a safari through the luscious landscape of Pandora. It’s an impossible but completely seductive world that invites the viewer’s total immersion in a state-of-the-art experience that for years to come will define what movies can achieve — not in duplicating our existence but in dreaming new ones.

JxSxPx's rating:

Raj Kapoor was the great star-auteur of India’s postcolonial golden age of movies — Cary Grant and Cecil B. DeMille in one handsome package. The ’50s films he headlined and directed became huge hits not just in his newly freed homeland but also across the Arab crescent from Indonesia to North Africa. Kapoor, who modeled his screen persona on Charlie Chaplin’s Little Tramp, was 26 when he filmed Awaara (The Tramp). A pompous judge (Kapoor’s father Prithviraj) disowns his wife (all-time Indian cinema mom Leela Chitnis) when some months after being kidnapped she returns pregnant; his baseless suspicion is that the bandit she’s been with is the father. In ignominy and in secret, she bears the judge’s son (Kapoor), who is raised a vagabond and, decades later, goes on trial before the judge. Sensational revelations!

As Kapoor sees it, the wellspring of these torrents of guilt is a society divided into Brahmins and outcasts. Beyond the social finger-pointing, Awaara is a glistening showcase for Kapoor and the great India siren Nargis (his lover onscreen and off); it features a sadistic-sexy beach scene and a dream sequence that starts in delirium and revs up to delicious. And of course it’s a musical, whose main song, “Awaara Hoon,” by the famed Shanker-Jaikishan duo, soared to the top of the pop charts in India, the U.S.S.R. and China.

As Kapoor sees it, the wellspring of these torrents of guilt is a society divided into Brahmins and outcasts. Beyond the social finger-pointing, Awaara is a glistening showcase for Kapoor and the great India siren Nargis (his lover onscreen and off); it features a sadistic-sexy beach scene and a dream sequence that starts in delirium and revs up to delicious. And of course it’s a musical, whose main song, “Awaara Hoon,” by the famed Shanker-Jaikishan duo, soared to the top of the pop charts in India, the U.S.S.R. and China.

JxSxPx's rating:

He made long, slow, painterly films about the misery of Europe’s postwar leisure class; he raised malaise to a fashion statement. Andrew Sarris described this style and method as “Antoniennui.” Yet the Italian director was narrative cinema’s first true modernist. His pristine imagery and elegant compositions taught moviegoers to watch a movie, not just see it. And viewing, or voyeuring, is the subject of Blowup, Michelangelo Antonioni’s first English-language feature. A sensation for its frank view of sex, drugs and rock ’n’ roll in swinging London, with music by the Yardbirds’ Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck, the movie was a surprise hit that helped liberate Hollywood from puritanism. Making the city over to suit his vision, he painted trees, streets, phone booths — all to demonstrate the power that a visual artist has over reality, and the limits of that power.

Blowup’s antihero, the magazine photographer Thomas (David Hemmings), does fashion shoots for the money; for art, he takes monochrome pictures of old men or that furtive couple kissing in the park. The kissing woman (Vanessa Redgrave) wants his roll of film, please; Thomas refuses. Later, in his developing room, he slowly concludes that he may have photographed a dead man — he may have the evidence of a murder. The scene in which he enlarges the photos, then scrutinizes them to find a meaning, is a 10½-min., virtually silent tour de force. It puts Thomas in the position of a director, seeking to impose narrative logic on shuffled images — or of someone at an Antonioni film, who is willing to follow a mysterious story that may offer no solution, only flashes of insight into a time, a place and the mind of a demanding, rewarding picture maker.

Blowup’s antihero, the magazine photographer Thomas (David Hemmings), does fashion shoots for the money; for art, he takes monochrome pictures of old men or that furtive couple kissing in the park. The kissing woman (Vanessa Redgrave) wants his roll of film, please; Thomas refuses. Later, in his developing room, he slowly concludes that he may have photographed a dead man — he may have the evidence of a murder. The scene in which he enlarges the photos, then scrutinizes them to find a meaning, is a 10½-min., virtually silent tour de force. It puts Thomas in the position of a director, seeking to impose narrative logic on shuffled images — or of someone at an Antonioni film, who is willing to follow a mysterious story that may offer no solution, only flashes of insight into a time, a place and the mind of a demanding, rewarding picture maker.

JxSxPx's rating:

Les Bonnes Femmes (1960)

As a young critic at the influential magazine Cahiers du Cinéma, Claude Chabrol wrote glowing reviews of Alfred Hitchcock’s films and, with his colleague Eric Rohmer, a book on the Master of Suspense. When he made his own films, Chabrol gave a sly Gallic accent to Hitchcock’s tales of men fatally obsessed with women. He was an artist of grimaces and whispers, an anatomizer of eroticism, a suave coroner of desire. When a man and a woman got together in a Chabrol movie, someone was sure to end up hurt — often dead, like the lovely Clothilde Joano in Les bonnes femmes.

In telling the story of four Paris shopgirls who are as eager for love as they are disappointed by it, the film contains comic scenes both light (a man at a swimming pool sucks in his gut when he is introduced to the girls, then lets it sag when a man walks by) and dark (the shop’s older cashier keeps as a relic the handkerchief of a condemned murderer). Chabrol and his favorite screenwriter, Paul Gégauff, send their sweetest character (Joano) toward ecstasy when she meets a suitor (Mario David) under the glittering ball above a dance hall, then end her life with a snap of the neck. Les bonnes femmes ends with a new young woman, hopes high, attracting the gaze of a new young man under the same spinning ball. And the dance goes on.

In telling the story of four Paris shopgirls who are as eager for love as they are disappointed by it, the film contains comic scenes both light (a man at a swimming pool sucks in his gut when he is introduced to the girls, then lets it sag when a man walks by) and dark (the shop’s older cashier keeps as a relic the handkerchief of a condemned murderer). Chabrol and his favorite screenwriter, Paul Gégauff, send their sweetest character (Joano) toward ecstasy when she meets a suitor (Mario David) under the glittering ball above a dance hall, then end her life with a snap of the neck. Les bonnes femmes ends with a new young woman, hopes high, attracting the gaze of a new young man under the same spinning ball. And the dance goes on.

Days of Heaven (1978)

The mystery man of serious cinema, Terrence Malick has not spoken in public for decades — and then only to students at the Paris university where he taught in the ’80s. When The Tree of Life, just his fifth feature in a 40-year career, won the Palme d’Or at the 2011 Cannes Film Festival, he was again absent. A philosophy major at Harvard and a Rhodes scholar at Oxford, Malick might have much to say about his rapturous, delphic movies. But he’s kept mum, so it’s left to his admirers to chart the vectors of Days of Heaven, the director’s second and in many ways most satisfying film. Bill (Richard Gere in his first starring role) and Abby (Brooke Adams) are a couple on the run. Pretending to be brother and sister, they get jobs working for a Texas farmer (playwright Sam Shepard, also in his first major film role) and plan to have Abby marry the farmer, thought to be dying, and profit from his estate. The Malick hallmarks are here: crafty-naive narration from an outsider (Linda Manz, as a teen cohort of the couple), a naturalist’s attention to landscape, a visual poet’s acute observation of all living things, an amazing attention to the symphony of rural sounds. (The film was one of the first to make inventive use of the Dolby system.) The Criterion DVD edition of Days of Heaven has plenty of commentary by Malick admirers. We’ll just say: See it. Watch and listen closely. Attend the dense cinematic tapestry of a mystic master.

JxSxPx's rating:

Gone with the Wind (1939)

Here’s why the all-time most popular movie (in terms of tickets sold) was not on our original All-TIME 100 Movies list: it is indefensible as social history; it lags in its second half; it lacks a strong directorial signature. All that leaves is the film’s epic ambition, its steam train of story propulsion, a ravishing visual design by William Cameron Menzies and performances of glamour and power. Which makes this superproduction of the Margaret Mitchell book the definitive Hollywood movie. No question that this is a producer’s, not a director’s project; David O. Selznick’s grand and niggling obsession stamps the movie like Kong’s footprint, while Victor Fleming shared helming chores with George Cukor when he wasn’t off directing The Wizard of Oz. O.K., so what? In its first two hours, moving with whirring assurance, GWTW establishes three pairs of potent contradictions: the mercantile North vs. the farmland South, the white gentry vs. their black slaves and the rakish male (Clark Gable as Rhett Butler) vs. the ferocious female (Vivien Leigh as Scarlett O’Hara). The longest, most expensive film made to that time, from the best-selling novel of its day, was also the ultimate woman’s picture, fully attuned to Scarlett’s charms, furies, whims and indomitable will. Leigh, a 25-year-old British actress in her first American movie, gave a performance of spectacular drive, complexity and star quality — which, on its own, would earn GWTW a ticket to inclusion in the updated All-TIME 100 Movies list.

JxSxPx's rating:

Toutes les histoires (1989)

In the ’50s, Jean-Luc Godard was a penetrating, iconoclastic critic for the film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma (along with François Truffaut and Claude Chabrol). In 1960 his debut feature Breathless (along with Truffaut’s The 400 Blows and Chabrol’s Les bonnes femmes) brought the French new wave of moviemakers crashing on international shores. In the half-century since, Godard has kept on astounding and confounding movie lovers. This show-and-tell lecture on film history — first conceived in 1978 and presented on French TV from 1987 to 1998 — is the creative capstone of Godard’s career. Histoire(s) crams the grand, sleazy spectacle of world cinema into a 4-hr., 24-min. love letter, an eloquent rant, a majestic atonal symphony. In his editorial hands, hundreds of film snippets collide: a few frames of a European or Hollywood masterpiece may run next to a shot of Hitler or Stalin or a porno clip, while quotes from Dante or Virginia Woolf flash on the screen. A snatch of the “Girl Hunter” ballet from The Band Wagon, with Cyd Charisse vamping Fred Astaire, plays over the lover’s monologue from Last Year at Marienbad. And throughout is Godard’s craggy voice, sometimes capricious, occasionally confessional — as when he says that making movies “was the only way of making, telling, realizing, that I have my own story. Without cinema, I wouldn’t exist; there would be no me.” Histoire(s) du Cinéma, which means both the history and the stories of movies, is a daunting, enthralling experience that turns all films into one giant Godard epic.

The Hurt Locker (2008)

U.S. soldiers in Iraq, especially before the 2007 surge, knew what to expect: 130° heat and streets full of men, women and kids, any one of whom could detonate an improvised explosive device and blow a street and all its people, American and Iraqi, to bits. In this hell storm, what’s left for an ordinary soldier to do? His job. Action-movie maven Kathryn Bigelow and screenwriter Mark Boal did theirs too — so well that The Hurt Locker, a scary, thrilling patrol of those Baghdad streets by men who defuse IEDs, won six Oscars, including Best Picture, Director and Screenplay. (The runner-up that year: Avatar, written and directed by Bigelow’s ex-husband James Cameron.)

When the leader of a bomb-disposal unit dies in action, the two survivors (Anthony Mackie and Brian Geraghty) get a new boss: William James (Jeremy Renner), a tough hombre energized by mortal danger. James is nuts, but he’s exactly the right kind of crazy for the job: ice-water nerves and a go-it-alone bravado match his ninja expertise. He has the cool aplomb, analytical acumen and attention to detail of a great athlete or a master serial killer — anyway, some gifted obsessive. Short of being there, you’ll never get closer to the on-the-ground immediacy of the Iraq or Afghanistan occupations, the sick tension, the toxic tang. This great, unflinching war film deserved its Oscars. We’d also award it a Medal of Honor.

When the leader of a bomb-disposal unit dies in action, the two survivors (Anthony Mackie and Brian Geraghty) get a new boss: William James (Jeremy Renner), a tough hombre energized by mortal danger. James is nuts, but he’s exactly the right kind of crazy for the job: ice-water nerves and a go-it-alone bravado match his ninja expertise. He has the cool aplomb, analytical acumen and attention to detail of a great athlete or a master serial killer — anyway, some gifted obsessive. Short of being there, you’ll never get closer to the on-the-ground immediacy of the Iraq or Afghanistan occupations, the sick tension, the toxic tang. This great, unflinching war film deserved its Oscars. We’d also award it a Medal of Honor.

JxSxPx's rating:

Killer of Sheep (1978) (1978)

A portrait of the Watts section of Los Angeles, made by one of its residents who was also a student at the American Film Institute, Killer of Sheep was barely released upon its completion in 1977. Thirty years later, on a Milestone Video DVD, the movie achieved its rightful stature as a work of uncompromising vision. Its plot is virtually nonexistent: Stan (Henry Gayle Sanders) works in a slaughterhouse; his wife (Kaycee Moore) is at home with their young son and daughter; neighbors drop by; Stan and a friend buy a junky motor for their car; the two men and their families go on a brief jaunt before the car breaks down. But the strength of Killer is in the details of a man, his family and his neighborhood. Charles Burnett, who made his film in reaction to the blaxploitation movies that depicted African-American males as dope-dealing supermen, trusts viewers to see the characters as he does — sympathetically and without judgment.

At the center of the nonaction is Stan, a quiet man who is ground down, worn out and fed up. He has lost the passion for his wife, who wonders what’s wrong; in the kitchen, she examines her face in the mirror of a pot lid. Later, in the living room, the couple slow-dances to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth.” She caresses his body, paws it, as he noncommittally keeps his hands on her thighs. When she passionately kisses his chest, he extracts himself and leaves. Standing alone, she picks up their daughter’s tiny shoes. The scene is elliptical, no loving or angry words spoken, but it’s a heartbreaker. So is this movie: a tender, searing evocation of hurts that can’t be expressed, little dreams too stubborn to die.

At the center of the nonaction is Stan, a quiet man who is ground down, worn out and fed up. He has lost the passion for his wife, who wonders what’s wrong; in the kitchen, she examines her face in the mirror of a pot lid. Later, in the living room, the couple slow-dances to Dinah Washington’s “This Bitter Earth.” She caresses his body, paws it, as he noncommittally keeps his hands on her thighs. When she passionately kisses his chest, he extracts himself and leaves. Standing alone, she picks up their daughter’s tiny shoes. The scene is elliptical, no loving or angry words spoken, but it’s a heartbreaker. So is this movie: a tender, searing evocation of hurts that can’t be expressed, little dreams too stubborn to die.

Letter from an Unknown Woman (1948)

“A shot that does not call for tracks/ Is agony for poor old Max,/ Who, separated from his dolly,/ Is wrapped in deepest melancholy./ Once, when they took away his crane,/ I thought he’d never smile again.” The actor James Mason’s tribute in verse acknowledged director Max Ophüls’ fondness for the long, elegant tracking shot. Movies, Ophüls thought, should move; his swooping shots would propel viewers over European streets, across drawing rooms and into the hearts of the women at the center of most of his movies. He is celebrated for such later French films as La Ronde, Le Plaisir and Lola Montès, but this Hollywood drama, written by Howard Koch (Casablanca, Mission to Moscow) from a Stefan Zweig story, shows Ophüls’ ability to raise novelettish romance to the sweetest, most soulful heights. The missive delivered to fashionable musician Stefan Brand (Louis Jourdan) begins, “By the time you read this letter, I may be dead.” The unknown woman is Lisa Berndl (Joan Fontaine), a child when she first spots her playboy hero; later they have an affair that is for Stefan a pleasing dalliance but for Lisa besotted destiny. Jourdan’s sleek charm nicely complements Fontaine’s gift for playing insecure lovelies, and Ophüls encases and embraces the pair in tracking shots that can convey ecstasy or emotional distance. Letter is the perfect companion for a rainy afternoon when you’re in the mood for a love story that both leads to death and transcends it.

JxSxPx's rating:

Napoleon (1927)

From Richard Schickel’s 1981 TIME review of a reissue of Napoleon: “On April 7, 1927, Charles de Gaulle and his friend, André Malraux, saw the Paris premiere of a new movie. At its end, the two great-men-to-be were on their feet, cheering. Malraux remembered De Gaulle waving his long arms and crying, ‘Bravo, magnifique!’ It is said that De Gaulle never forgot the images of glory he found that evening in Abel Gance’s epic reconstruction of another young soldier’s climb to greatness, Napoleon.”

No art form can duplicate the size and scope of historical film epics. They conjure the size, the spectacle, the very movieness of movies. To do film justice to the most powerful military figure in French history, Gance conceived the grandest of all silent-movie dreams: six features chronicling Napoleon’s extraordinary life. He ran out of money and sponsors after just one film, but it’s a beaut, whose restored versions run between 4 and 5 1/2 hrs. Beginning with a snow fight involving the child, embracing his love for Josephine (Gina Manès) and his irresistible rise through the tumult of the French Revolution and reaching its climax with the victorious Italian campaign, Gance’s biopic is as heroic and driven as its subject. Creating “a new alphabet for the cinema,” the director employed wildly swinging cameras to mime the milling chaos of revolutionary life and death, and for the final battle scenes, he sprayed the action across three screens — Cinerama and CinemaScope 25 years early. Over the years, Napoleon was recut, mutilated and all but lost; film historian Kevin Brownlow devoted decades to reviving it at its original epic length and scope. That the movie is not available on DVD in the U.S. is a crime against cinema genius.

No art form can duplicate the size and scope of historical film epics. They conjure the size, the spectacle, the very movieness of movies. To do film justice to the most powerful military figure in French history, Gance conceived the grandest of all silent-movie dreams: six features chronicling Napoleon’s extraordinary life. He ran out of money and sponsors after just one film, but it’s a beaut, whose restored versions run between 4 and 5 1/2 hrs. Beginning with a snow fight involving the child, embracing his love for Josephine (Gina Manès) and his irresistible rise through the tumult of the French Revolution and reaching its climax with the victorious Italian campaign, Gance’s biopic is as heroic and driven as its subject. Creating “a new alphabet for the cinema,” the director employed wildly swinging cameras to mime the milling chaos of revolutionary life and death, and for the final battle scenes, he sprayed the action across three screens — Cinerama and CinemaScope 25 years early. Over the years, Napoleon was recut, mutilated and all but lost; film historian Kevin Brownlow devoted decades to reviving it at its original epic length and scope. That the movie is not available on DVD in the U.S. is a crime against cinema genius.

A Separation (2011)

When the Motion Picture Academy this year gave its Best Foreign-Language Film prize to A Separation — the first Iranian feature to win an Oscar — skeptics might have seen the award as a political statement. At a time when Iran was under rhetorical fire from the Israeli government and Republican presidential candidates, the liberal Academy members were offering an Oscar as an olive branch. What’s more likely is that the voters were endorsing the complexities of Asghar Farhadi’s fascinating drama. Beginning with a married woman’s plea for divorce, it escalates into a culture war on many fronts: secular vs. religious, urban vs. rural, middle class vs. working class. In this battle, the collateral damage may be the children — and sometimes the truth.

In a Tehran court, Simin (Leila Hatami) wants a divorce from Nader (Peyman Moadi) so she can take their daughter to live abroad; Nader says he must stay home to care for his Alzheimer’s-afflicted father. When Simin moves in with her parents while awaiting the judge’s ruling, she and Nader hire Razieh (Sareh Bayat), a devout woman whose husband is in debtor’s prison. Soon one life is imperiled, another lost, in actions stemming from the characters’ plausible, even noble motives. A master twister of plots and personalities, Farhadi gets exemplary performances from his ensemble cast, notably the redheaded Hatami and the saintly, volcanic Bayat. Every cramped or conflicted emotion plays luminously across Bayat’s face — a soul crying for God’s liberating help — in a drama that spans continents and cultures to connect with moviegoers in the Motion Picture Academy and beyond.

In a Tehran court, Simin (Leila Hatami) wants a divorce from Nader (Peyman Moadi) so she can take their daughter to live abroad; Nader says he must stay home to care for his Alzheimer’s-afflicted father. When Simin moves in with her parents while awaiting the judge’s ruling, she and Nader hire Razieh (Sareh Bayat), a devout woman whose husband is in debtor’s prison. Soon one life is imperiled, another lost, in actions stemming from the characters’ plausible, even noble motives. A master twister of plots and personalities, Farhadi gets exemplary performances from his ensemble cast, notably the redheaded Hatami and the saintly, volcanic Bayat. Every cramped or conflicted emotion plays luminously across Bayat’s face — a soul crying for God’s liberating help — in a drama that spans continents and cultures to connect with moviegoers in the Motion Picture Academy and beyond.

JxSxPx's rating:

The Seventh Seal (1957)

The Colbert Report has an occasional segment called “Cheating Death,” which is introduced by the image of Stephen facing the hooded figure of Death over a chessboard. It’s one of many pop-culture tributes over the past half-century — a Woody Allen short-story parody, the Van Halen song “The Seventh Seal,” whole segments of Monty Python and the Holy Grail — to Ingmar Bergman’s medieval morality play. With this grand pageant of a knight (Max von Sydow) who plays chess with Death (Bengt Ekerot), putting his soul on the line to save a few lives during a season of plague, Bergman proclaimed his huge ambition and cinematic mastery. Its influence was immediate and extraordinary: intelligent youngsters in Europe and America saw it and, transfixed like Saul on the road to Tarsus, instantly recognized the difference between the movies they’d been raised on and the films that were worth admiration and scholarly study. For better or worse, The Seventh Seal helped spawn a generation of film critics, as well as the serious film culture that prevailed until Jaws and Star Wars re-established movies as playthings for sophisticated children. Beyond that, it’s a brilliant thesis on life and death, love and fear, morality and mortality. Or so says one of those kids who saw the picture as a teenager and can still feel the first shiver of its greatness.

JxSxPx's rating:

Nobody in postwar Hollywood called the crime genre “film noir”; that was a later French appellation. A visual and emotional mood more than a genre, noir wreathed its characters in misty doom, none more seductively than the star-crossed lovers in Nicholas Ray’s first feature. Based on the Edward Anderson novel Thieves Like Us (remade in the ’70s by Robert Altman), the movie fictionalized the story of real-life outlaws Clyde Barrow and Bonnie Parker and glamorized them as almost-innocents speeding away from an unjust society toward a doom they don’t deserve.

Bowie (Farley Granger), a 23-year-old who’s spent the past seven years behind bars, has just broken out with two other cons; hoping to go straight, he falls in love with Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell), daughter of one of the gang’s confederates. Granger, who would star as weak-willed playboys in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope and Strangers on a Train, looks more prep school than prison-bred, but his sullen, saturnine aspect makes an ideal complement to O’Donnell’s pale sweetness, especially as captured in Ray’s gigantic close-ups. Though Bowie is the ex-con and Keechie his loyal help meet, she is often the dominant figure: driving their car, for instance, and patting his head as he rests on her shoulder. Keechie will be Bowie’s lover, his mother and, if she can, his savior. Good luck with that dream: in the noir cosmos, nobody lives forever.

Bowie (Farley Granger), a 23-year-old who’s spent the past seven years behind bars, has just broken out with two other cons; hoping to go straight, he falls in love with Keechie (Cathy O’Donnell), daughter of one of the gang’s confederates. Granger, who would star as weak-willed playboys in Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope and Strangers on a Train, looks more prep school than prison-bred, but his sullen, saturnine aspect makes an ideal complement to O’Donnell’s pale sweetness, especially as captured in Ray’s gigantic close-ups. Though Bowie is the ex-con and Keechie his loyal help meet, she is often the dominant figure: driving their car, for instance, and patting his head as he rests on her shoulder. Keechie will be Bowie’s lover, his mother and, if she can, his savior. Good luck with that dream: in the noir cosmos, nobody lives forever.

JxSxPx's rating:

The Third Man (1949)

Viennese noir: streets wet with guilt, oblique camera angles, chases through city sewers, a smiling villain whose selling of black-market diluted penicillin killed people. The finest, grimmest, gaudiest collaboration of novelist-screenwriter Graham Greene and director Carol Reed (The Fallen Idol, Our Man in Havana) also marked a collision of many cultural forces. To Major Calloway (Trevor Howard), the British officer who oversees this section of postwar Vienna, the American writer Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) is a clueless cowboy, naively tainting everyone he touches. Anna Schmidt (Alida Valli), the displaced beauty in whose sad eyes the stories of many lost wars can be read, rejects Holly’s ardor for the memorial love of the vanished Harry Lime (Orson Welles). This charismatic scoundrel is believed buried, so why does Holly keep glimpsing the shadow of the third man? We might also ask why a film so bleak and desperate plays out to the jaunty thrum of Anton Karas’ zither music. Perhaps to give this nightmare bedtime story the lilt of a contemporary fable. Its particulars are tragic but its telling strangely tonic — not just in Welles’ grinning apparition, like a Cheshire cat wanted for mass murder, but also in the sordid verve of Robert Krasker’s cinematography. Even the last, long shot in a graveyard, as Anna strolls defiantly past a waiting Holly, is a joke of cinematic geometry, as if the Road Runner had strolled instead of zoomed past a Wile E. Coyote destined to be disappointed.

JxSxPx's rating:

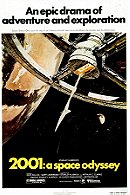

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968)

What’s happening at the beginning (when apes discover a giant slab and hurl a bone in the air)? What’s the meaning of the ending (when an astronaut ages in space and morphs into a star child)? Not many science-fiction films encourage the audience to ask those questions. An essay on man’s destiny, 2001 was for some of its late-’60s viewers a light show, a head trip, needing no earthbound explanations. Making the first mainstream movie to foreground its special effects, Kubrick and his brilliant young technicians imagined the cosmos without today’s digital gadgets: all the wizardry was photomechanical, achieved within the camera — including the movie hyperspace that Luke Skywalker would fly through nine years later. George Lucas has said that 2001 “was hugely inspirational to me. If he could do it, I can do it.” Except that Star Wars was a very sophisticated kids’ movie, with Saturday-matinee thrills and warp-drive plot thrust. Kubrick made an interspace art film; it had wonder, as in awe and wonder, as in head-scratching bafflement.

A year after his space movie came out, man walked on the moon. But less than four years later, the manned exploration of other planets ceased. And the director died two years before the actual 2001. He left behind this very Kubrickian thought: “The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent … However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.”

A year after his space movie came out, man walked on the moon. But less than four years later, the manned exploration of other planets ceased. And the director died two years before the actual 2001. He left behind this very Kubrickian thought: “The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent … However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.”

JxSxPx's rating:

Vertigo (1958)

Scottie Ferguson (James Stewart) is a retired detective whose fear of heights while on the force had led to the death of a policeman. Now an old college chum has put Scottie on the trail of his disturbed wife Madeleine (Kim Novak), who believes herself possessed by the spirit of her suicidal great-great-grandmother. Scottie follows Madeleine up and down the hills of San Francisco, a vertiginous setting where even the streets have lost their balance. At first he is a detective tracking his suspect; then he is an infatuated adolescent duped by glamour. He could also be a moviegoer transfixed by the light on the screen, or a director turning an actress into a fantasy figure, or a psychoanalyst falling in love with his patient — falling, always falling, into and out of a dream that keeps slipping beyond his reach. When Madeleine falls to her death from a great height, Scottie finds himself still in love, in a necrophilic passion for what was or may never have been.

In adapting a novel by the French authors of Diabolique, Hitchcock builds his seductive, nightmare logic, notably in a 10-min. slow-pursuit sequence with no words, only Bernard Herrmann’s hypnotic score. The movie points Stewart’s farm-boy common sense inexorably toward sexual neurosis and fashions Novak’s street-girl sexuality into a dream girl swathed in soft light. Vertigo is Hitchcock’s creepy crowning achievement in implicating moviegoers in his own cinematic fetishes — voyeurism, the movie’s essential impulse, raised to art.

In adapting a novel by the French authors of Diabolique, Hitchcock builds his seductive, nightmare logic, notably in a 10-min. slow-pursuit sequence with no words, only Bernard Herrmann’s hypnotic score. The movie points Stewart’s farm-boy common sense inexorably toward sexual neurosis and fashions Novak’s street-girl sexuality into a dream girl swathed in soft light. Vertigo is Hitchcock’s creepy crowning achievement in implicating moviegoers in his own cinematic fetishes — voyeurism, the movie’s essential impulse, raised to art.

JxSxPx's rating:

WALL·E (2008)

Most smart filmmakers want to parade their facility with all the tools in the modern movie box. Andrew Stanton, the director and co-writer of the Pixar animated feature WALL•E, experimented with what talking pictures could plausibly do without. Talking, for example: the first third of the movie has almost no dialogue. How about depriving the two main characters — the humble, lonely trash compacter WALL•E and his space princess EVE — of emotional signifiers like a mouth, eyebrows, shoulders, elbows? Yet with all the limitations he imposed on himself and his robot stars, Stanton still connected with a huge audience. Great science-fiction love stories (there aren’t many) will do that. So will futurist adventures that evoke the splendor of the movie past. A dirt-of-the-earth guy hooking up with the ultimate ethereal gal, WALL•E and EVE could be the 29th century version of Tracy and Hepburn or of Jonah Hill and any attractive woman. It hardly matters that the movie is not quite silent when it blends art and heart as spectacularly as WALL•E does.

JxSxPx's rating:

People who voted for this also voted for

R.E.M.: Top 10 Songs

Undisputed Masterpiece Albums

Close Up Beautiful

The 100 Greatest Goddamned Films of All Time

In ♥ with...

Beautiful Eniko Mihalik

Wild Wild West

Cigarette Cards: Association Football (1910)

Super Bowl LII

Road Trip

Escape velocity

Beautiful US Faces - Ashley Heller

Favorite Images - August 2018

Total Film's 75 Greatest Animated Movies

Tales of the Jazz Age

More lists from JxSxPx

Rolling Stone 200: The Essential Rock Collection

Slant’s 100 Greatest Horror Films – 2018 Edition

R&RHOF: The 200 Definitive Albums

The 25 Greatest Christmas Albums of All Time

RS: 40 Greatest Punk Albums of All-Time

500 CDs You Must Own Before You Die!

Uncut Magazine - 200 Greatest Albums Of All Time

Login

Login

24

24

7.7

7.7

7.4

7.4