PopMatter's Essential Film Performances - 2012

Sort by:

Showing 50 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

PopMatters follows up last year's hugely popular 100 Essential Female and Male Performances feature with 50 additions to the essentials list.

Dance, Girl, Dance (1940)

UNDER THE RADAR

Lucille Ball

How on earth could an outright icon such as Lucille Ball ever be considered “Under the Radar”, you might ask. Yes, everyone’s favorite redhead became a household name for her brilliant eponymous television comedy and her legendary performance as a 1950s housewife that still rings hilariously true today and is beloved basically globally. Everyone knows Lucy. Yet, curiously, we rarely talk about Lucille Ball as a film actress of formidable skill, and it is high time this changes.

Pioneering director Dorothy Arzner, one of very few female directors working at the time, saw in proto-pioneer Ball something we rarely think of her as: the vamp, the bad girl, the one who uses her body and looks to get what she wants. Bubbles and her alter ego Tiger Lily White are part old-fashioned 1940s movie dames, part hybridized femmes fatale. Think the va-va-va-voom of the Rockettes colliding with Joan Blondell’s smart mouth. There’s a lot of sex in Dance, Girl, Dance, mainly courtesy of Ball. She’s tough, funny, and magnetic as Bubbles/Tiger Lilly finding a nice balance between the cat and the claw as a good time burlesque dancer out to seize whatever opportunity she can to further her career and her own security.

There’s a sparkle in her eye and on her ear, a vivaciousness in her body language. Bubbles/Tiger Lily seems wildly unpredictable, dangerous even at times, because she’s smarter, sexier and more determined than anyone else in the room. And she never really apologizes, which makes this performance all the more memorable and allows each bon mot she lets loose crackle with electricity. As one male character says to her: “Give ‘em all you got, baby!” Her reply? “They couldn’t take it.” Packed with nerve, Ball’s performance leaves much to be admired, and as directed by Arzner, she exposes each one in brilliantly subversive way, embracing the challenges of pure physical comedy and expert timing, singing and dancing with equal grace.

However, there is a raw undertone to her work here, a hard-to-pin down sparkling diamond hardness, the kind that is fascinating to stare at, but that can also cut deep. It is Ball’s choice to play her character with a strong, bitchy edge that elevates the characterization beyond just another working class dancehall girl of that era. She brings what can only be surmised is a sense of scrappy reality to the part of a woman trying to get ahead in life on her own steam, using whatever resource is at hand. Whether it’s money, power, or her friend’s man, nothing is off limits if it means Bubbles/Tiger Lilly gets her way. She may pay friends debts and attempt—in her own self-cherishing way—to “help” her fellow dancers achieve infamy through public humiliation, but that’s about the extent of this wild and sharp sex kitten’s good nature. It is this kind of impressive versatility on film that, along with her television achievements, cements Ball’s place in the pantheon of all-time great comediennes.

-Matt Mazur

Lucille Ball

How on earth could an outright icon such as Lucille Ball ever be considered “Under the Radar”, you might ask. Yes, everyone’s favorite redhead became a household name for her brilliant eponymous television comedy and her legendary performance as a 1950s housewife that still rings hilariously true today and is beloved basically globally. Everyone knows Lucy. Yet, curiously, we rarely talk about Lucille Ball as a film actress of formidable skill, and it is high time this changes.

Pioneering director Dorothy Arzner, one of very few female directors working at the time, saw in proto-pioneer Ball something we rarely think of her as: the vamp, the bad girl, the one who uses her body and looks to get what she wants. Bubbles and her alter ego Tiger Lily White are part old-fashioned 1940s movie dames, part hybridized femmes fatale. Think the va-va-va-voom of the Rockettes colliding with Joan Blondell’s smart mouth. There’s a lot of sex in Dance, Girl, Dance, mainly courtesy of Ball. She’s tough, funny, and magnetic as Bubbles/Tiger Lilly finding a nice balance between the cat and the claw as a good time burlesque dancer out to seize whatever opportunity she can to further her career and her own security.

There’s a sparkle in her eye and on her ear, a vivaciousness in her body language. Bubbles/Tiger Lily seems wildly unpredictable, dangerous even at times, because she’s smarter, sexier and more determined than anyone else in the room. And she never really apologizes, which makes this performance all the more memorable and allows each bon mot she lets loose crackle with electricity. As one male character says to her: “Give ‘em all you got, baby!” Her reply? “They couldn’t take it.” Packed with nerve, Ball’s performance leaves much to be admired, and as directed by Arzner, she exposes each one in brilliantly subversive way, embracing the challenges of pure physical comedy and expert timing, singing and dancing with equal grace.

However, there is a raw undertone to her work here, a hard-to-pin down sparkling diamond hardness, the kind that is fascinating to stare at, but that can also cut deep. It is Ball’s choice to play her character with a strong, bitchy edge that elevates the characterization beyond just another working class dancehall girl of that era. She brings what can only be surmised is a sense of scrappy reality to the part of a woman trying to get ahead in life on her own steam, using whatever resource is at hand. Whether it’s money, power, or her friend’s man, nothing is off limits if it means Bubbles/Tiger Lilly gets her way. She may pay friends debts and attempt—in her own self-cherishing way—to “help” her fellow dancers achieve infamy through public humiliation, but that’s about the extent of this wild and sharp sex kitten’s good nature. It is this kind of impressive versatility on film that, along with her television achievements, cements Ball’s place in the pantheon of all-time great comediennes.

-Matt Mazur

JxSxPx's rating:

Portrait of Jennie (1948)

LIFE SUPPORT

Ethel Barrymore

“I’m an old maid and nobody knows more about love than an old maid,” says Ethel Barrymore’s Spinny, the Upper East Side spinster-gallerist in William Dieterle’s stunning curio of a film, Portrait of Jennie. At this point in her career, Barrymore was a stage legend, her film appearances often reluctant and fleeting, though celebrated nonetheless. (During the mid-to-late-1940s, Barrymore got four Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress, winning one.)

And so it is that Barrymore appears in Portrait of Jennie as the archetypal crone, a role she repeated often, but, aside perhaps from her stint in Vincente Minnelli’s portion of The Story of Three Loves, never did better. Spinny is the life coach of hapless Hawthornian artist Eben Adams, played by Joseph Cotten. She buys a poor flower sketch from him at the start of the film, out of pity—and a bit, as her bulging eyes and pursed lips suggest, out of lust. Later, he finds his muse, Jenny (Jennifer Jones), who exists out of time, maturing rapidly as a ghost, or an idea. Spinny recognizes that Eben must paint Jenny if he is to excel as an artist, and she encourages him, wistful and wise in her aging virginity.

Spinny and Jenny are opposites in the film, a subject-object dichotomy brilliantly embodied by Barrymore and Jones: one, the great interpreter, always observing and commenting; the other, a Hollywood ingénue, her lines secondary to her beauty. “There ought to be something eternal about a woman,” says Cecil Kellaway’s Mr. Matthews, Spinny’s colleague, when the film’s titular portrait is revealed. Spinny seems aware that this means more than he knows—that it has resonance for her as well.

Barrymore shines in Portrait of Jennie when she bids Eban goodbye as he makes his way to the coastal town of “Land’s End Light,” where he meets Jennie to try to rectify her haunted tale with romantic union. “You’re tough; the sea wouldn’t get you,” says Eban in response to Spinny’s grandmotherly warning for him to be safe. “Tough ones drown too, you know,” she responds, a bit lovelorn, and clearly aware that her own fate, unlike Jennie’s, is unalterably mortal.

-David Balzer

Ethel Barrymore

“I’m an old maid and nobody knows more about love than an old maid,” says Ethel Barrymore’s Spinny, the Upper East Side spinster-gallerist in William Dieterle’s stunning curio of a film, Portrait of Jennie. At this point in her career, Barrymore was a stage legend, her film appearances often reluctant and fleeting, though celebrated nonetheless. (During the mid-to-late-1940s, Barrymore got four Academy Award nominations for Best Supporting Actress, winning one.)

And so it is that Barrymore appears in Portrait of Jennie as the archetypal crone, a role she repeated often, but, aside perhaps from her stint in Vincente Minnelli’s portion of The Story of Three Loves, never did better. Spinny is the life coach of hapless Hawthornian artist Eben Adams, played by Joseph Cotten. She buys a poor flower sketch from him at the start of the film, out of pity—and a bit, as her bulging eyes and pursed lips suggest, out of lust. Later, he finds his muse, Jenny (Jennifer Jones), who exists out of time, maturing rapidly as a ghost, or an idea. Spinny recognizes that Eben must paint Jenny if he is to excel as an artist, and she encourages him, wistful and wise in her aging virginity.

Spinny and Jenny are opposites in the film, a subject-object dichotomy brilliantly embodied by Barrymore and Jones: one, the great interpreter, always observing and commenting; the other, a Hollywood ingénue, her lines secondary to her beauty. “There ought to be something eternal about a woman,” says Cecil Kellaway’s Mr. Matthews, Spinny’s colleague, when the film’s titular portrait is revealed. Spinny seems aware that this means more than he knows—that it has resonance for her as well.

Barrymore shines in Portrait of Jennie when she bids Eban goodbye as he makes his way to the coastal town of “Land’s End Light,” where he meets Jennie to try to rectify her haunted tale with romantic union. “You’re tough; the sea wouldn’t get you,” says Eban in response to Spinny’s grandmotherly warning for him to be safe. “Tough ones drown too, you know,” she responds, a bit lovelorn, and clearly aware that her own fate, unlike Jennie’s, is unalterably mortal.

-David Balzer

JxSxPx's rating:

THE CLASSICS YOU SHOULD HAVE SEEN BY NOW

John Barrymore

It must have taken a lot of energy to star in a great screwball comedy. Watch Rosalind Russell in the second half of His Girl Friday, for example. At a screwball climax, the situation runs at a fever pitch, and the actors have to keep up with the pace. Sometimes, the great screwball films feel designed to keep the audience in a continuous belly laugh for their duration. One such performance is John Barrymore’s in Howard Hawks’ screwball classic Twentieth Century.

You don’t know mania until you’ve seen this performance. John Barrymore is ferocious. He’s playing Oscar Jaffe, a flamboyant, egomaniacal thee-ay-tuh producer opposite Carole Lombard in her breakthrough role. Combined, the first generation of Barrymores brought more prestige to the “lesser” art of film acting than anyone else, save Lillian Gish. By the time Twentieth Century came along, this foundation was firmly in place, and Barrymore just wanted to have fun. With every crazed swoop of the arm and defeated snarl, he chews the scenery and mocks his own temperamental reputation.

It’s not just the outright wackiness of the role that’s so exciting, it’s the utter perverseness of it. I’ve never quite fully reconciled the joy of watching this movie with the film’s outrageous cruelty; most of the humor in the movie comes from Jaffe’s sadism. If Hitchcock ever actually said actors were cattle, Jaffe would’ve called it an understatement. He treats the Carole Lombard character so badly, you almost have to feel bad for laughing at her expense. Credit must be given to John Barrymore, for imbuing such a thankless role with a delicate balance of savagery, histrionics, and heart. It’s a shame that Twentieth Century was his last truly great film role, but his actorly grandeur and superbly over-the-top comedic timing positively spark.

-Austin Dale

John Barrymore

It must have taken a lot of energy to star in a great screwball comedy. Watch Rosalind Russell in the second half of His Girl Friday, for example. At a screwball climax, the situation runs at a fever pitch, and the actors have to keep up with the pace. Sometimes, the great screwball films feel designed to keep the audience in a continuous belly laugh for their duration. One such performance is John Barrymore’s in Howard Hawks’ screwball classic Twentieth Century.

You don’t know mania until you’ve seen this performance. John Barrymore is ferocious. He’s playing Oscar Jaffe, a flamboyant, egomaniacal thee-ay-tuh producer opposite Carole Lombard in her breakthrough role. Combined, the first generation of Barrymores brought more prestige to the “lesser” art of film acting than anyone else, save Lillian Gish. By the time Twentieth Century came along, this foundation was firmly in place, and Barrymore just wanted to have fun. With every crazed swoop of the arm and defeated snarl, he chews the scenery and mocks his own temperamental reputation.

It’s not just the outright wackiness of the role that’s so exciting, it’s the utter perverseness of it. I’ve never quite fully reconciled the joy of watching this movie with the film’s outrageous cruelty; most of the humor in the movie comes from Jaffe’s sadism. If Hitchcock ever actually said actors were cattle, Jaffe would’ve called it an understatement. He treats the Carole Lombard character so badly, you almost have to feel bad for laughing at her expense. Credit must be given to John Barrymore, for imbuing such a thankless role with a delicate balance of savagery, histrionics, and heart. It’s a shame that Twentieth Century was his last truly great film role, but his actorly grandeur and superbly over-the-top comedic timing positively spark.

-Austin Dale

JxSxPx's rating:

Strange Days (1995)

LIFE SUPPORT

Angela Bassett

When we first see her navigating the mean streets of a then-futuristic millennial Los Angeles as limousine driver Lornette Mason (more fittingly referred to throughout by her nickname, “Mace”), Angela Bassett is the literal personification of the vehicle she sits at the helm of: sleek, imposing, beautiful and impenetrable. It is an exterior that is proven to be both accurate and deceptive in the alternately dazzling and complex Strange Days, as Mace’s steely armor is gradually revealed to be shielding a thicket of emotional live wires every bit as much as it is protecting her physically from a world teetering on the edge of violent chaos. It’s a duality that makes Mace the most fascinating and resonant character scattered amongst the Rogues gallery of disgraced ex-cops, techno-druggies, desperate criminals and entertainment industry sleaze balls that populate this vibrant slice of sci-fi noir, locating Bassett’s Mace as the film’s center of gravity both in terms of its point-of-view and its thematic weight.

Set in an L.A. still reeling from the fallout of the Rodney King verdict and subsequent riots of 1992, James Cameron and Jay Cocks’ ambitiously and even bravely topical script allows for both a literally ass kicking African American heroine and an uncommented-upon interracial romance, as Mace follows, rescues and assists unrequited love interest Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) through a seedy underworld of cover-ups, hate crimes and double crosses all centered around a frightening and seductive brand of virtual reality as the new drug of choice.

That Bassett bears the weight of all of this in what is essentially a supporting role (Fiennes is terrific in the lead, but his no-less-complicated role requires him to be every bit as frantic and colorful as the material) is as much of a testament to her strength, dignity, range and fearlessness as an actress as the role call of crucial real life figures, from Rosa Parks to Tina Turner, from Michael Jackson’s mother to Malcolm X’s wife Betty Shabazz, that she brought to life on screen. “Memories were meant to fade,” she lectures Fiennes in one crucial moment, but Bassett’s is one performance that is certain to remain vividly alive in the mind of anyone who witnesses it.

-Jer Fairall

Angela Bassett

When we first see her navigating the mean streets of a then-futuristic millennial Los Angeles as limousine driver Lornette Mason (more fittingly referred to throughout by her nickname, “Mace”), Angela Bassett is the literal personification of the vehicle she sits at the helm of: sleek, imposing, beautiful and impenetrable. It is an exterior that is proven to be both accurate and deceptive in the alternately dazzling and complex Strange Days, as Mace’s steely armor is gradually revealed to be shielding a thicket of emotional live wires every bit as much as it is protecting her physically from a world teetering on the edge of violent chaos. It’s a duality that makes Mace the most fascinating and resonant character scattered amongst the Rogues gallery of disgraced ex-cops, techno-druggies, desperate criminals and entertainment industry sleaze balls that populate this vibrant slice of sci-fi noir, locating Bassett’s Mace as the film’s center of gravity both in terms of its point-of-view and its thematic weight.

Set in an L.A. still reeling from the fallout of the Rodney King verdict and subsequent riots of 1992, James Cameron and Jay Cocks’ ambitiously and even bravely topical script allows for both a literally ass kicking African American heroine and an uncommented-upon interracial romance, as Mace follows, rescues and assists unrequited love interest Lenny Nero (Ralph Fiennes) through a seedy underworld of cover-ups, hate crimes and double crosses all centered around a frightening and seductive brand of virtual reality as the new drug of choice.

That Bassett bears the weight of all of this in what is essentially a supporting role (Fiennes is terrific in the lead, but his no-less-complicated role requires him to be every bit as frantic and colorful as the material) is as much of a testament to her strength, dignity, range and fearlessness as an actress as the role call of crucial real life figures, from Rosa Parks to Tina Turner, from Michael Jackson’s mother to Malcolm X’s wife Betty Shabazz, that she brought to life on screen. “Memories were meant to fade,” she lectures Fiennes in one crucial moment, but Bassett’s is one performance that is certain to remain vividly alive in the mind of anyone who witnesses it.

-Jer Fairall

JxSxPx's rating:

The Blue Gardenia (1953)

UNDER THE RADAR

Anne Baxter

“Do you know what a mermaid’s downfall is?”

Anne Baxter’s turn as Norah in Fritz Lang’s bombastic, sharply funny noir has her playing both of the classic types found in this genre: the anti-hero and the femme fatale. In this rarified world, it is highly unusual for women to be driving all of the action, so in this respect, Lange’s The Blue Gardenia could be called a “feminoir” and Baxter’s daffy, deft work as the woman at the center of the film’s mystery is a marvel of physical comedy and working class chutzpah.

As she demonstrated in her Oscar-winning performance in Elia Kazan’s The Razor’s Edge (1946) and perhaps in her most famous work opposite Bette Davis in All About Eve (1950), Baxter’s versatility as an actress enabled her to inhabit a wide range of characters (she was trained by the legendary Maria Ouspenskaya, after all). As Norah, a woman who stands accused of murder following a long, drunken night out after being jilted by her fiancee, the actress is put through some demanding paces, including playing both comedic and dramatic drunk scenes. Norah, who is as convinced of her guilt as the police, must piece together (through meticulously-constructed flashbacks) the truth about her fateful night out with a lech who ends up dead, and watching Baxter’s increasing paranoia, her lovelorn, broken-hearted telephone operator feels surprisingly modern even today.

Lang’s working class ladies’ milieu is punchy, a bit wicked, standing the test of time as a sharp look at single gals and just how tough it is to land a great catch. A timeless story, really. Norah is a reckless, jilted lover and the character feels like an anomaly in the world of noir: a passionate, grounded female protagonist who is equal parts comedienne and tragedienne. There is a vividness about her work, something bright, eager and instinctual that makes Norah feel real. Watching the mystery unravel with such balance and fairness expertly etched into the characterization is riveting and indeed rare.

-MM

Anne Baxter

“Do you know what a mermaid’s downfall is?”

Anne Baxter’s turn as Norah in Fritz Lang’s bombastic, sharply funny noir has her playing both of the classic types found in this genre: the anti-hero and the femme fatale. In this rarified world, it is highly unusual for women to be driving all of the action, so in this respect, Lange’s The Blue Gardenia could be called a “feminoir” and Baxter’s daffy, deft work as the woman at the center of the film’s mystery is a marvel of physical comedy and working class chutzpah.

As she demonstrated in her Oscar-winning performance in Elia Kazan’s The Razor’s Edge (1946) and perhaps in her most famous work opposite Bette Davis in All About Eve (1950), Baxter’s versatility as an actress enabled her to inhabit a wide range of characters (she was trained by the legendary Maria Ouspenskaya, after all). As Norah, a woman who stands accused of murder following a long, drunken night out after being jilted by her fiancee, the actress is put through some demanding paces, including playing both comedic and dramatic drunk scenes. Norah, who is as convinced of her guilt as the police, must piece together (through meticulously-constructed flashbacks) the truth about her fateful night out with a lech who ends up dead, and watching Baxter’s increasing paranoia, her lovelorn, broken-hearted telephone operator feels surprisingly modern even today.

Lang’s working class ladies’ milieu is punchy, a bit wicked, standing the test of time as a sharp look at single gals and just how tough it is to land a great catch. A timeless story, really. Norah is a reckless, jilted lover and the character feels like an anomaly in the world of noir: a passionate, grounded female protagonist who is equal parts comedienne and tragedienne. There is a vividness about her work, something bright, eager and instinctual that makes Norah feel real. Watching the mystery unravel with such balance and fairness expertly etched into the characterization is riveting and indeed rare.

-MM

JxSxPx's rating:

Winter Light (1963)

THE CLASSICS YOU SHOULD HAVE SEEN BY NOW

Gunnar Bjornstrand

In Winter Light, everyone is experiencing a crisis of faith of some sort: faith in a lover, faith in humanity, faith in suffering. But no crisis is more profound than that of Tomas Ericsson, a Lutheran pastor whose questioning of his relationship with God has made him question his very being.

Gunnar Björnstrand’s performance as Tomas is a lesson in subtly. Tomas keeps his breakdown private, pushing it inside himself. He responds to “God’s silence” with his own silence. The crisis is repressed and it only breaks through the surface every now and then, coming out as the flu and in coughs and fits of exhaustion. Otherwise, it is kept swallowed, and that is what is most amazing about Björnstrand’s feat. As an actor he can create a life-altering agony and then suppress it. Where other actors would want to emote, Björnstrand chooses to retreat, to utterly shun the very thing that is driving his character.

Björnstrand’s performance is made all the more challenging by Sven Nykvist’s cinematography. The camera fixes an unblinking gaze on Tomas, making every motion and every facial expression a subject to study and contemplate. As an actor, Björnstrand must be at his most aware while seeming totally unaware. Without pure dedication to the role and without being at the height of his craft, the game would be up and the illusion totally shattered.

This is what the priest is going through as well, but Tomas cannot pull it off as well as Björnstrand. Tomas’ audience is only a small congregation, but he’s crumbling, losing his own character because it has become too much to bear. In questioning his faith he questions his role in life, and so he cannot give to his job the dedication that Björnstrand gives to his. While preaching—both during and after a Sunday mass—Tomas’ speeches carry the seriousness of the whole universe, but his words have little meaning. Tomas cannot talk straight, cannot articulate the demons that are churning beneath his skin, ripping at his soul. There’s no substance behind his words because Tomas fears there’s no substance in existence, and Björnstrand is able to convey, with minimal movement and maximum effort, that this is a man who doesn’t even know if he can believe in himself.

-Daniel Tovrov

Gunnar Bjornstrand

In Winter Light, everyone is experiencing a crisis of faith of some sort: faith in a lover, faith in humanity, faith in suffering. But no crisis is more profound than that of Tomas Ericsson, a Lutheran pastor whose questioning of his relationship with God has made him question his very being.

Gunnar Björnstrand’s performance as Tomas is a lesson in subtly. Tomas keeps his breakdown private, pushing it inside himself. He responds to “God’s silence” with his own silence. The crisis is repressed and it only breaks through the surface every now and then, coming out as the flu and in coughs and fits of exhaustion. Otherwise, it is kept swallowed, and that is what is most amazing about Björnstrand’s feat. As an actor he can create a life-altering agony and then suppress it. Where other actors would want to emote, Björnstrand chooses to retreat, to utterly shun the very thing that is driving his character.

Björnstrand’s performance is made all the more challenging by Sven Nykvist’s cinematography. The camera fixes an unblinking gaze on Tomas, making every motion and every facial expression a subject to study and contemplate. As an actor, Björnstrand must be at his most aware while seeming totally unaware. Without pure dedication to the role and without being at the height of his craft, the game would be up and the illusion totally shattered.

This is what the priest is going through as well, but Tomas cannot pull it off as well as Björnstrand. Tomas’ audience is only a small congregation, but he’s crumbling, losing his own character because it has become too much to bear. In questioning his faith he questions his role in life, and so he cannot give to his job the dedication that Björnstrand gives to his. While preaching—both during and after a Sunday mass—Tomas’ speeches carry the seriousness of the whole universe, but his words have little meaning. Tomas cannot talk straight, cannot articulate the demons that are churning beneath his skin, ripping at his soul. There’s no substance behind his words because Tomas fears there’s no substance in existence, and Björnstrand is able to convey, with minimal movement and maximum effort, that this is a man who doesn’t even know if he can believe in himself.

-Daniel Tovrov

JxSxPx's rating:

FROM PAGE TO SCREEN

Beulah Bondi

Barkley and Lucy Cooper are an elderly couple with five grown children. Their children are a bit self-centered and preoccupied with their own lives. Luckily, their romance has never wavered, and as long as they have each other, they have someone to depend on. Unfortunately the Great Depression hits them hard, and they lose their home to foreclosure. None of their children are willing to take in both of them, so they must separate temporarily. This separation grows longer and longer. Eventually, Bark becomes ill and has to be sent to his daughter Addie in California. Lucy and Bark have one last afternoon together in New York before they must say goodbye to each other forever.

This is the sad story of Make Way For Tomorrow, Leo McCarey’s triumphantly sad masterpiece. It seems over the top doesn’t it? A little too melodramatic? You’d think so, wouldn’t you. Think again. Make Way For Tomorrow steers clear of histrionics and becomes a humanist tragedy of staggering proportions. Orson Welles said this film could make a stone cry. It’s not quite the story that makes you cry so much as the heartbreaking central performance by the Beulah Bondi.

Bondi was the quintessential ‘old woman’ of the movies. Even in her younger years, she made a long career playing old women. You’d know her from films like It’s a Wonderful Life; and in fact, she ended up playing Jimmy Stewart’s mother four times. She was in her 40s when she played Lucy Cooper, but you’d never know it. It’s not just because you could do a lot with age make-up in black and white. She was a just a brilliant chameleon.

Lucy Cooper is an everywoman with a quiet strength. Even at her most pathetic—annoying her daughter-in-law’s bridge class with her loopy, Granny behavior—she wins you over with her generous spirit. And when Lucy bears her soul, which she does many times in the film, she will break your heart. Bondi takes lines like “You were always my favorite child” and overwhelms you. She’s so hypnotic that I never remember exactly how she does it. Perhaps it’s because she knows your grandparents. Or maybe she’s just a genius.

People always talk about the final scene in the film. Bark and Lucy are at the train station and she must say goodbye to him forever. I won’t spoil the words she says to him, but when you do see the film, you might be watching the saddest scene in all of movies. I certainly can’t think of anything sadder. And it’s all because of Beulah Bondi.

-AD

Beulah Bondi

Barkley and Lucy Cooper are an elderly couple with five grown children. Their children are a bit self-centered and preoccupied with their own lives. Luckily, their romance has never wavered, and as long as they have each other, they have someone to depend on. Unfortunately the Great Depression hits them hard, and they lose their home to foreclosure. None of their children are willing to take in both of them, so they must separate temporarily. This separation grows longer and longer. Eventually, Bark becomes ill and has to be sent to his daughter Addie in California. Lucy and Bark have one last afternoon together in New York before they must say goodbye to each other forever.

This is the sad story of Make Way For Tomorrow, Leo McCarey’s triumphantly sad masterpiece. It seems over the top doesn’t it? A little too melodramatic? You’d think so, wouldn’t you. Think again. Make Way For Tomorrow steers clear of histrionics and becomes a humanist tragedy of staggering proportions. Orson Welles said this film could make a stone cry. It’s not quite the story that makes you cry so much as the heartbreaking central performance by the Beulah Bondi.

Bondi was the quintessential ‘old woman’ of the movies. Even in her younger years, she made a long career playing old women. You’d know her from films like It’s a Wonderful Life; and in fact, she ended up playing Jimmy Stewart’s mother four times. She was in her 40s when she played Lucy Cooper, but you’d never know it. It’s not just because you could do a lot with age make-up in black and white. She was a just a brilliant chameleon.

Lucy Cooper is an everywoman with a quiet strength. Even at her most pathetic—annoying her daughter-in-law’s bridge class with her loopy, Granny behavior—she wins you over with her generous spirit. And when Lucy bears her soul, which she does many times in the film, she will break your heart. Bondi takes lines like “You were always my favorite child” and overwhelms you. She’s so hypnotic that I never remember exactly how she does it. Perhaps it’s because she knows your grandparents. Or maybe she’s just a genius.

People always talk about the final scene in the film. Bark and Lucy are at the train station and she must say goodbye to him forever. I won’t spoil the words she says to him, but when you do see the film, you might be watching the saddest scene in all of movies. I certainly can’t think of anything sadder. And it’s all because of Beulah Bondi.

-AD

JxSxPx's rating:

Come Back, Little Sheba (1952)

FROM PAGE TO SCREEN

Shirley Booth

Shirley Booth won an Oscar for her portrayal of sweet, yet slovenly housewife Lola Delaney (as well as a Tony for her stage interpretation of the role). While Lola may be the haggard, middle-aged haus frau modern audiences are accustomed to seeing, her character was a silver screen anomaly in the ‘50s. Her life has been a string of disappointments. Not only did her pooch (the titular Sheba who never materializes) run away, but Lola’s marriage to chiropractor “Doc” Delaney (Burt Lancaster), a recovering alcoholic, is as loveless as it gets.

When the Delaneys board a pretty, young co-ed, Doc develops a crush on her—reminded of a time when Lola was young and beautiful. Lola, on the other hand, views their new tenant as the daughter she never had. The film eventually divulges the Delaneys’ secret at the root of their marital disharmony: Doc resents marrying Lola because she was pregnant and lost the baby, rendering her sterile. Despite his flaws and the fact he largely ignores her, Lola remains proud of her husband, even affectionately (and ironically) calling him “Daddy”.

Lola could have devolved into caricature with her squeaky, nasal voice, shambling about her house and scratching herself in a slip and bathrobe. Yet, Booth delivers a sensitive, nuanced portrayal, seamlessly transitioning between adoration, fear, and joy. Lola’s quirks are natural, not exaggerated. She’s lazy and when she wipes her mouth with her sleeve or eats crumbs off the table, these small actions aren’t played for comedy. Rather, Lola is a woman who sees little reason to be the civilized beauty she once was. She’s desperate for company and excitement, prone to (intentionally comedic) flights of fancy like grooving to bongo music on the radio; so lost in reverie she’s oblivious that she’s being watched.

“Oblivious” seems an adequate descriptor for Lola, but thanks to the subtleties of Booth’s performance, the viewer soon realizes that Lola is well-aware of what is going on around her. She just tries to content herself with the little she has in order to cope with tragedy. When Doc states that their lost dog should have never grown old, Lola clearly understands this comment is directed at her. This understanding is further demonstrated with a mixture of sweetness and sentimentality when she tells him, “You didn’t know I was gonna get old and fat and sloppy… I didn’t know that, either, Doc.” Her voice bears no indignation. Just a hint of hope.

-Lana Cooper

Shirley Booth

Shirley Booth won an Oscar for her portrayal of sweet, yet slovenly housewife Lola Delaney (as well as a Tony for her stage interpretation of the role). While Lola may be the haggard, middle-aged haus frau modern audiences are accustomed to seeing, her character was a silver screen anomaly in the ‘50s. Her life has been a string of disappointments. Not only did her pooch (the titular Sheba who never materializes) run away, but Lola’s marriage to chiropractor “Doc” Delaney (Burt Lancaster), a recovering alcoholic, is as loveless as it gets.

When the Delaneys board a pretty, young co-ed, Doc develops a crush on her—reminded of a time when Lola was young and beautiful. Lola, on the other hand, views their new tenant as the daughter she never had. The film eventually divulges the Delaneys’ secret at the root of their marital disharmony: Doc resents marrying Lola because she was pregnant and lost the baby, rendering her sterile. Despite his flaws and the fact he largely ignores her, Lola remains proud of her husband, even affectionately (and ironically) calling him “Daddy”.

Lola could have devolved into caricature with her squeaky, nasal voice, shambling about her house and scratching herself in a slip and bathrobe. Yet, Booth delivers a sensitive, nuanced portrayal, seamlessly transitioning between adoration, fear, and joy. Lola’s quirks are natural, not exaggerated. She’s lazy and when she wipes her mouth with her sleeve or eats crumbs off the table, these small actions aren’t played for comedy. Rather, Lola is a woman who sees little reason to be the civilized beauty she once was. She’s desperate for company and excitement, prone to (intentionally comedic) flights of fancy like grooving to bongo music on the radio; so lost in reverie she’s oblivious that she’s being watched.

“Oblivious” seems an adequate descriptor for Lola, but thanks to the subtleties of Booth’s performance, the viewer soon realizes that Lola is well-aware of what is going on around her. She just tries to content herself with the little she has in order to cope with tragedy. When Doc states that their lost dog should have never grown old, Lola clearly understands this comment is directed at her. This understanding is further demonstrated with a mixture of sweetness and sentimentality when she tells him, “You didn’t know I was gonna get old and fat and sloppy… I didn’t know that, either, Doc.” Her voice bears no indignation. Just a hint of hope.

-Lana Cooper

JxSxPx's rating:

Requiem for a Dream (2000)

THE DARK SIDE

Ellen Burstyn

Burstyn’s Requiem for a Dream transformation is a cinematic cousine to the great character work of Lon Chaney or Boris Karloff, or perhaps even Robert De Niro in Raging Bull, which makes Sara Goldfarb a classically-defined monster in many ways. In Monster Culture (Seven Theses), writer Jeffrey Jerome Cohen says that “everyone is a monster on Halloween night”, but what connects everyday “monster” Sara to the traditional creature narrative discussed by Cohen is how Burstyn’s body “literally incorporates fear, desire, anxiety, and fantasy”. By going so far into the physical (and mental) dimensions of the character, Burstyn holds up a dark mirror to the character’s soul, showcasing a woman who is pathetic, who makes mistakes, who is doing the best she knows how, and who, in the end, provides a revealing, strangely relatable catharsis for viewers.

After all, the essential function of any true “monster” is not to scare, but to educate, to warn humans of their own dangerous bodies. Sara’s body, and the body of “the monster”, according to Cohen, is “incoherent, [and] resists any systematic structuration. And so the monster is dangerous [...] demanding a radical rethinking of boundary and normality.” And so is the task of playing of playing Sara Goldfarb, a character we are simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by, just as we are by monsters; both “call horrid attention to the border that cannot—must not—be crossed,” according to Cohen.

Utilizing the gestural, the corporeal, the facial, and the vocal as building blocks for conveying the mood of Requiem for a Dream‘s hardscrabble milieu, Burstyn, by playing Sara, not only proved to the world that actors of her familiarity and caliber do possess the ability to become completely different people, but that female performers of her generation (she was 66 at the time of filming), should never be discounted because of their age. The star seemingly suppressed herself to occupy a character that would be the biggest challenge of her career, and took her biggest risk, which resulted in perhaps her most successful, adventurous acting performance to date. An acting performance that redefined her yet again.

Speaking directly to the drug culture-savvy Generations X and Y, Aronofsky, acting as an ambassador for the new guard, introduced Burstyn’s old guard school of Actors Studio discipline to many film-goers who likely hadn’t even been born during the height of the actresses’ popularity in the 1970s. All you need to do is watch Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (Martin Scorsese, 1974) and Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000) in a double bill, and you will see with your own eyes that Burstyn is never the same woman onscreen. She constantly transforms.

-MM

Ellen Burstyn

Burstyn’s Requiem for a Dream transformation is a cinematic cousine to the great character work of Lon Chaney or Boris Karloff, or perhaps even Robert De Niro in Raging Bull, which makes Sara Goldfarb a classically-defined monster in many ways. In Monster Culture (Seven Theses), writer Jeffrey Jerome Cohen says that “everyone is a monster on Halloween night”, but what connects everyday “monster” Sara to the traditional creature narrative discussed by Cohen is how Burstyn’s body “literally incorporates fear, desire, anxiety, and fantasy”. By going so far into the physical (and mental) dimensions of the character, Burstyn holds up a dark mirror to the character’s soul, showcasing a woman who is pathetic, who makes mistakes, who is doing the best she knows how, and who, in the end, provides a revealing, strangely relatable catharsis for viewers.

After all, the essential function of any true “monster” is not to scare, but to educate, to warn humans of their own dangerous bodies. Sara’s body, and the body of “the monster”, according to Cohen, is “incoherent, [and] resists any systematic structuration. And so the monster is dangerous [...] demanding a radical rethinking of boundary and normality.” And so is the task of playing of playing Sara Goldfarb, a character we are simultaneously attracted to and repulsed by, just as we are by monsters; both “call horrid attention to the border that cannot—must not—be crossed,” according to Cohen.

Utilizing the gestural, the corporeal, the facial, and the vocal as building blocks for conveying the mood of Requiem for a Dream‘s hardscrabble milieu, Burstyn, by playing Sara, not only proved to the world that actors of her familiarity and caliber do possess the ability to become completely different people, but that female performers of her generation (she was 66 at the time of filming), should never be discounted because of their age. The star seemingly suppressed herself to occupy a character that would be the biggest challenge of her career, and took her biggest risk, which resulted in perhaps her most successful, adventurous acting performance to date. An acting performance that redefined her yet again.

Speaking directly to the drug culture-savvy Generations X and Y, Aronofsky, acting as an ambassador for the new guard, introduced Burstyn’s old guard school of Actors Studio discipline to many film-goers who likely hadn’t even been born during the height of the actresses’ popularity in the 1970s. All you need to do is watch Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore (Martin Scorsese, 1974) and Darren Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream (2000) in a double bill, and you will see with your own eyes that Burstyn is never the same woman onscreen. She constantly transforms.

-MM

JxSxPx's rating:

Claudine (1974) (1974)

UNDER THE RADAR

Diahann Carroll

From the moment she steps onto the scene in Claudine, Diahann Carroll commands your attention. You see, she’s not your stereotypical down-on-her-luck black woman from the projects waving her finger in your face and speaking at ridiculously high volumes.

Rather, our heroine is just coming home from a long day’s work, eight-plus hours of cleaning after folks and cooking warm meals for them. As a single mother of six, you’d think she’d be going home to the same tasks. But instead, she walks through the front door interrupting the natural chaos of her apartment—son blasting music, daughter hogging the bathroom, etc. But with just one look at her face, the whole apartment quiets down.

It’s that respect that Carroll’s title character demands from not only her children, but from the audience, whose preconceived notions about her are quickly evaporated once she introduces herself to us. She’s tough but not abrasive, aware but not haughty. In essence, she represents many single women—of any color—today. While Claudine isn’t a weak character, she’s certainly not a perfect one. She’s not neat. And she doesn’t claim to always have the answers, like she just leapt out of an after school special. She goes through many of the same issues women face today—trying to provide for her kids, being a good mother, a good person, dating as a single parent, etc.

That said, viewers empathize with her, while not having to sympathize or pity a downtrodden character. In other words, we march with her instead of looking down at her. As respected as she comes across onscreen, those who know her best—her kids—still run to her side when her heart gets broken after a romantic disappointment, which speaks to Carroll’s ability to humanize a character whose sensitivity isn’t first evident. Carroll creates a character that goes far outside the tight constraints of many of today’s leading female characters of color. She shows us a whole character, not one whose fractured story orbits around others. We get to see her fail, and we see her succeed. She’s juggling a lot and understandably feels the urge to wring a few necks, but we always get her, we get why. She’s just one of the gals, relatable, real.

-Candice Frederick

Diahann Carroll

From the moment she steps onto the scene in Claudine, Diahann Carroll commands your attention. You see, she’s not your stereotypical down-on-her-luck black woman from the projects waving her finger in your face and speaking at ridiculously high volumes.

Rather, our heroine is just coming home from a long day’s work, eight-plus hours of cleaning after folks and cooking warm meals for them. As a single mother of six, you’d think she’d be going home to the same tasks. But instead, she walks through the front door interrupting the natural chaos of her apartment—son blasting music, daughter hogging the bathroom, etc. But with just one look at her face, the whole apartment quiets down.

It’s that respect that Carroll’s title character demands from not only her children, but from the audience, whose preconceived notions about her are quickly evaporated once she introduces herself to us. She’s tough but not abrasive, aware but not haughty. In essence, she represents many single women—of any color—today. While Claudine isn’t a weak character, she’s certainly not a perfect one. She’s not neat. And she doesn’t claim to always have the answers, like she just leapt out of an after school special. She goes through many of the same issues women face today—trying to provide for her kids, being a good mother, a good person, dating as a single parent, etc.

That said, viewers empathize with her, while not having to sympathize or pity a downtrodden character. In other words, we march with her instead of looking down at her. As respected as she comes across onscreen, those who know her best—her kids—still run to her side when her heart gets broken after a romantic disappointment, which speaks to Carroll’s ability to humanize a character whose sensitivity isn’t first evident. Carroll creates a character that goes far outside the tight constraints of many of today’s leading female characters of color. She shows us a whole character, not one whose fractured story orbits around others. We get to see her fail, and we see her succeed. She’s juggling a lot and understandably feels the urge to wring a few necks, but we always get her, we get why. She’s just one of the gals, relatable, real.

-Candice Frederick

The Docks of New York (1928)

UNDER THE RADAR

Betty Compson

One of the most prolific stars to cross over from silent to sound film, Betty Compson, despite an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for her turn in The Barker (1928), remains largely spoken of in hushed tones in the dialog on actresses of this era. Though a fair amount of her films have been lost and her ability to successfully make the transition between the old style and new style of acting would become the focus of her legend, her work for director Josef von Sternberg in his sharply-etched expressionist masterwork The Docks of New York remains vital and lusty. The sheer frenzy that in-your-face eroticism must have sent movie-goers of that era into can only be imagined, but as Mae (“a girl”, natch), Compson’s slatternly, depressed, blowsy creation induces a blush or two even today . All nervously penetrating eyes topped with a frizzy shock of blonde hair can be seen in glimpses in the work of women from Jean Harlow to Madonna (in fact, Erotica-era Madonna owes much to Compson’s performance here).

Compson gives a lived-in, refreshingly bleak performance of great skill and nuance, appropriately saucy and tarty when need be, but also chock full of shipyard grit. She revels in the nightlife and the seamy culture that congregates on the waterfront. She is the queen of this underworld, of these derelict sea captains, miscreants, and toughs. When her suicide attempt—she is broke, desperate and turning tricks— is thwarted by Bill (George Bancroft) a stoker who is immediately fascinated by her, marrying her after fishing her out of the drink. Mae emerges from an impossible situation as a hothouse flower in full bloom. Witness her sensual, bloody-rare eyeballing of a sailor’s beefy, tattooed forearm, where Compson adds a deliriously, deliciously carnal twist to the ogling (please remember, this was 1928 and women weren’t (quite yet) encouraged to openly objectify men). Compson finds an impressive balance in this hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold archetype, never quite making her likable, playing loose and fast with the audience’s perceptions of her twisty moral codes and bad choices. Just like Mae might with everyone she comes into contact with.

-MM

Betty Compson

One of the most prolific stars to cross over from silent to sound film, Betty Compson, despite an Academy Award nomination for Best Actress for her turn in The Barker (1928), remains largely spoken of in hushed tones in the dialog on actresses of this era. Though a fair amount of her films have been lost and her ability to successfully make the transition between the old style and new style of acting would become the focus of her legend, her work for director Josef von Sternberg in his sharply-etched expressionist masterwork The Docks of New York remains vital and lusty. The sheer frenzy that in-your-face eroticism must have sent movie-goers of that era into can only be imagined, but as Mae (“a girl”, natch), Compson’s slatternly, depressed, blowsy creation induces a blush or two even today . All nervously penetrating eyes topped with a frizzy shock of blonde hair can be seen in glimpses in the work of women from Jean Harlow to Madonna (in fact, Erotica-era Madonna owes much to Compson’s performance here).

Compson gives a lived-in, refreshingly bleak performance of great skill and nuance, appropriately saucy and tarty when need be, but also chock full of shipyard grit. She revels in the nightlife and the seamy culture that congregates on the waterfront. She is the queen of this underworld, of these derelict sea captains, miscreants, and toughs. When her suicide attempt—she is broke, desperate and turning tricks— is thwarted by Bill (George Bancroft) a stoker who is immediately fascinated by her, marrying her after fishing her out of the drink. Mae emerges from an impossible situation as a hothouse flower in full bloom. Witness her sensual, bloody-rare eyeballing of a sailor’s beefy, tattooed forearm, where Compson adds a deliriously, deliciously carnal twist to the ogling (please remember, this was 1928 and women weren’t (quite yet) encouraged to openly objectify men). Compson finds an impressive balance in this hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold archetype, never quite making her likable, playing loose and fast with the audience’s perceptions of her twisty moral codes and bad choices. Just like Mae might with everyone she comes into contact with.

-MM

JxSxPx's rating:

Ace in the Hole (1951)

UNDER THE RADAR

Kirk Douglas

Journalists don’t come more cynical than Kirk Douglas’s Chuck Tatum, a big-city writer who lands in Albuquerque after drinking, womanizing, and otherwise sabotaging his career. Now he has to hustle up a job at the Albuquerque Sun-Bulletin, whose only distinction is that it’s the paper published nearest to where his car broke down. Yet Tatum manages to treat even his entrance into town like a royal procession, riding in his towed car as if he were a king touring his lands.

Douglas is on screen for most Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole, and the “big carnival” which gave the film its alternate title can be seen as the physical extension of his own corrupt persona. Scorning the paper’s motto, “Tell the truth,” Tatum is only interested in finding a story so big that his reporting will be picked up by the wire services and he’ll be rehired by his old paper in New York. Opportunity presents itself when a local man (Leo Minosa, played by Richard Benedict) is trapped in an abandoned mine; contrary to the rules of ethical journalism, as well as those of human decency, Tatum inserts himself into the story and delays Leo’s rescue in order to milk the potential tragedy for all it’s worth.

It’s worth quite a bit, at least in the short term—news of Leo’s plight draws other reporters, tourists, and politicians, as well as any hustler eager for a chance to work the crowd. The area near the mine quickly comes to resemble the midway of a state fair, complete with cotton candy and rides on the Ferris wheel. Tatum positions himself as the ringmaster of the resulting circus, cultivating a relationship with the naïve Leo and bribing the local sheriff to be sure it’s Tatum’s story and no one else’s.

Ace in the Hole may be the darkest of Billy Wilder’s films, and Chuck Tatum the most unredeemable of his characters; that’s saying quite a bit for the man who directed Sunset Boulevard and Double Indemnity. Yet you can’t turn away from Douglas’ performance, which is as luridly fascinating as watching a train wreck in slow motion. Perhaps we, like the fictional crowds in Ace in the Hole, are always ready to witness human tragedy, as long as it’s happening to someone else.

-Sarah Boslaugh

Kirk Douglas

Journalists don’t come more cynical than Kirk Douglas’s Chuck Tatum, a big-city writer who lands in Albuquerque after drinking, womanizing, and otherwise sabotaging his career. Now he has to hustle up a job at the Albuquerque Sun-Bulletin, whose only distinction is that it’s the paper published nearest to where his car broke down. Yet Tatum manages to treat even his entrance into town like a royal procession, riding in his towed car as if he were a king touring his lands.

Douglas is on screen for most Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole, and the “big carnival” which gave the film its alternate title can be seen as the physical extension of his own corrupt persona. Scorning the paper’s motto, “Tell the truth,” Tatum is only interested in finding a story so big that his reporting will be picked up by the wire services and he’ll be rehired by his old paper in New York. Opportunity presents itself when a local man (Leo Minosa, played by Richard Benedict) is trapped in an abandoned mine; contrary to the rules of ethical journalism, as well as those of human decency, Tatum inserts himself into the story and delays Leo’s rescue in order to milk the potential tragedy for all it’s worth.

It’s worth quite a bit, at least in the short term—news of Leo’s plight draws other reporters, tourists, and politicians, as well as any hustler eager for a chance to work the crowd. The area near the mine quickly comes to resemble the midway of a state fair, complete with cotton candy and rides on the Ferris wheel. Tatum positions himself as the ringmaster of the resulting circus, cultivating a relationship with the naïve Leo and bribing the local sheriff to be sure it’s Tatum’s story and no one else’s.

Ace in the Hole may be the darkest of Billy Wilder’s films, and Chuck Tatum the most unredeemable of his characters; that’s saying quite a bit for the man who directed Sunset Boulevard and Double Indemnity. Yet you can’t turn away from Douglas’ performance, which is as luridly fascinating as watching a train wreck in slow motion. Perhaps we, like the fictional crowds in Ace in the Hole, are always ready to witness human tragedy, as long as it’s happening to someone else.

-Sarah Boslaugh

JxSxPx's rating:

Melancholia (2011)

THE DARK SIDE

Kirsten Dunst

I’m convinced that Kirsten Dunst is the best actress of her generation and has been for many years. Still, the remarkable range she has shown throughout her career—in films spanning from Interview with a Vampire to Bring It On to Marie Antoinette—didn’t fully prepare me for the refined, mature and deeply soulful nuances that Dunst brings to the elegantly manic depressive character of Justine in Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia. In a performance that plays like a piece of classical music (perhaps “Death and the Maiden”), Dunst navigates an extreme spectrum of highs and lows, uncovering the troubled mind of a young bride who must come to terms with impending doom. What power does the planet Melancholia have over Justine? To quote another Von Trier film, Dancer in the Dark, she’s “seen it all, there is no more to see”. Her burden seems to be bearing the knowledge of the world’s destruction before anyone else, and this knowledge (temporarily) unravels her.

Before her premonitions are eventually be proven true, Justine is put through the wringer, ravaged by debilitating anxieties and depression. Following an intense, reptilian-eyed showdown with her caretaker sister, Justine, freed of the anxiety that once pummeled her into the ground, sets out to construct a “magic cave” shelter with her nephew in preparation for the last act’s planetary collision as her sister falls apart. Dunst swings her character’s arc into one of redemption, of strength, just as Earth is destroyed, without it ever being cliched or gooey. Justine’s nephew calls her “Auntie Steel Breaker”, a term that is never really explained, but I think that implies he sees her as being strong enough to break through steel, she is his hero. When he calls her this while she is in the throes of despair, laying paralyzed with grief, it is hard to listen to.However, by the film’s end, as the planet crumbles, Dunst reveals Justine’s solid core and earns that moniker as this once fragile creature shockingly becomes the story’s most grounded, sensible, strong voice.

No matter how flawed the heroines of Von Trier’s oeuvre may or may not be, each one of these women is expertly drawn by the performer and Von Trier. These are wholly original, daring and cinematic female characters. Whether you love him or hate him, he is still one of the only major working auteurs to consistently depict interesting, complicated women with such razor sharp edges and subtleties. Dunst’s prickly, coolly venomous portrayal of Justine is a work of vision and bravado that hints on even greater things to come. Bring it on, apocalypse.

-MM

Kirsten Dunst

I’m convinced that Kirsten Dunst is the best actress of her generation and has been for many years. Still, the remarkable range she has shown throughout her career—in films spanning from Interview with a Vampire to Bring It On to Marie Antoinette—didn’t fully prepare me for the refined, mature and deeply soulful nuances that Dunst brings to the elegantly manic depressive character of Justine in Lars Von Trier’s Melancholia. In a performance that plays like a piece of classical music (perhaps “Death and the Maiden”), Dunst navigates an extreme spectrum of highs and lows, uncovering the troubled mind of a young bride who must come to terms with impending doom. What power does the planet Melancholia have over Justine? To quote another Von Trier film, Dancer in the Dark, she’s “seen it all, there is no more to see”. Her burden seems to be bearing the knowledge of the world’s destruction before anyone else, and this knowledge (temporarily) unravels her.

Before her premonitions are eventually be proven true, Justine is put through the wringer, ravaged by debilitating anxieties and depression. Following an intense, reptilian-eyed showdown with her caretaker sister, Justine, freed of the anxiety that once pummeled her into the ground, sets out to construct a “magic cave” shelter with her nephew in preparation for the last act’s planetary collision as her sister falls apart. Dunst swings her character’s arc into one of redemption, of strength, just as Earth is destroyed, without it ever being cliched or gooey. Justine’s nephew calls her “Auntie Steel Breaker”, a term that is never really explained, but I think that implies he sees her as being strong enough to break through steel, she is his hero. When he calls her this while she is in the throes of despair, laying paralyzed with grief, it is hard to listen to.However, by the film’s end, as the planet crumbles, Dunst reveals Justine’s solid core and earns that moniker as this once fragile creature shockingly becomes the story’s most grounded, sensible, strong voice.

No matter how flawed the heroines of Von Trier’s oeuvre may or may not be, each one of these women is expertly drawn by the performer and Von Trier. These are wholly original, daring and cinematic female characters. Whether you love him or hate him, he is still one of the only major working auteurs to consistently depict interesting, complicated women with such razor sharp edges and subtleties. Dunst’s prickly, coolly venomous portrayal of Justine is a work of vision and bravado that hints on even greater things to come. Bring it on, apocalypse.

-MM

JxSxPx's rating:

LIFE SUPPORT

Gary Farmer

He enters the screen grimacing and hovering as he attempts to remove a bullet from Johnny Depp. With an abrupt, fierce disregard for white men, Nobody, as played by Gary Farmer becomes the spiritual healer and trusted sidekick in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. The gruff and decisive facade that Farmer gives our anti-hero, dubbed “Nobody”, is merely a shadow, an imitation. The stunning achievement of Farmer’s performance is how he slowly emerges as a big man with a soft heart. Farmer enters William Blake’s life to rescue him but it is he himself who needs rescuing. Farmer beautifully shows the audience how Nobody is an outsider in his land. He roams alone and he struggles to find his identity amidst the ruins of his stolen sense of history.

And this is precisely what is so startling about Farmer’s performance: as a supporting player to the presence of Depp, you find it is Farmer’s journey that is equally as compelling, if not far more. Farmer’s performance carries an eccentric sense of loneliness. You can tell he has been on his own for a very long time and that is how he likes it. With limited dialogue and an intermittent presence on the screen, Farmer is able to give the mysterious Nobody such depth with his lived-in performance. Farmer, at the time of release of this film when his performance was receiving much deserved praise, revealed that he was able to draw on his own personal quest to find his Native American roots, which becomes apparent as the story unfolds. Farmer channels the dispossession that underlines Nobody’s existence into every hint of affection for William Blake. Farmer’s calm and reassuring presence does not deliver a happy ending. The way Farmer maintains his distance and assumes his role as a guide to Blake so hauntingly tells us that he knows the best he can give this man is dignity in death. Farmer’s final farewell is as menacing as his entry. His expression portrays both grief and an innate understanding that the spirit of Blake can no longer be denied.

-Kylie Little

Gary Farmer

He enters the screen grimacing and hovering as he attempts to remove a bullet from Johnny Depp. With an abrupt, fierce disregard for white men, Nobody, as played by Gary Farmer becomes the spiritual healer and trusted sidekick in Jim Jarmusch’s Dead Man. The gruff and decisive facade that Farmer gives our anti-hero, dubbed “Nobody”, is merely a shadow, an imitation. The stunning achievement of Farmer’s performance is how he slowly emerges as a big man with a soft heart. Farmer enters William Blake’s life to rescue him but it is he himself who needs rescuing. Farmer beautifully shows the audience how Nobody is an outsider in his land. He roams alone and he struggles to find his identity amidst the ruins of his stolen sense of history.

And this is precisely what is so startling about Farmer’s performance: as a supporting player to the presence of Depp, you find it is Farmer’s journey that is equally as compelling, if not far more. Farmer’s performance carries an eccentric sense of loneliness. You can tell he has been on his own for a very long time and that is how he likes it. With limited dialogue and an intermittent presence on the screen, Farmer is able to give the mysterious Nobody such depth with his lived-in performance. Farmer, at the time of release of this film when his performance was receiving much deserved praise, revealed that he was able to draw on his own personal quest to find his Native American roots, which becomes apparent as the story unfolds. Farmer channels the dispossession that underlines Nobody’s existence into every hint of affection for William Blake. Farmer’s calm and reassuring presence does not deliver a happy ending. The way Farmer maintains his distance and assumes his role as a guide to Blake so hauntingly tells us that he knows the best he can give this man is dignity in death. Farmer’s final farewell is as menacing as his entry. His expression portrays both grief and an innate understanding that the spirit of Blake can no longer be denied.

-Kylie Little

Down to the Bone (2005)

UNDER THE RADAR

Vera Farminga

Telling the story of a drug-addicted mother of two, maybe-wife of one, and lover of another, Down to the Bone feels like a movie we’ve seen a thousand times before. First she’s addicted. Then she goes to rehab. Then she relapses. Then, well, you get it. So what pulls Down to the Bone up from the dreck of all the other indie druggie movies? Simply put, one element: Vera Farmiga in a performance of such guts and vision that it justly won her the Los Angeles Film Critics’ Best Actress prize.

Unlike many of her peers, Farmiga’s take on a highly-functioning junkie is one of subtle grace. Watching Irene is like watching the world’s most exhausted thief pull a job night after night. She knows she’s doing something wrong—a trigger pulled by the near-constant presence of her children—but she can’t stop. Watching Irene is like watching the world’s most exhausted thief pull a job over and over again, night after night.., That brand of cringe-inducing self-awareness makes the viewer feel like she feels like she’ll get caught eventually, whether by her boss, sponsor, or the police, and she’s just stealing as much time as she can before it happens. You keep waiting for the breakdown. The emotional outburst all Hollywood drug addicts reach after the worst has happened—usually running out of drugs. Yet Farmiga refuses to go there. She doesn’t want to take the easy way out, even if the story surrounding her (perhaps) does in certain respects. Instead, Farmiga crafts an indelible and original model of addiction for generations of her peers to imitate—the silent sufferer.

Some may dismiss the movie (as most mainstream audiences did) and Farmiga because both are so laid back, too-natural almost. It’s fitting and, when you think about it, fierce. She makes Down to the Bone worth looking up.

-Matt Mazur and Ben Travers

Vera Farminga

Telling the story of a drug-addicted mother of two, maybe-wife of one, and lover of another, Down to the Bone feels like a movie we’ve seen a thousand times before. First she’s addicted. Then she goes to rehab. Then she relapses. Then, well, you get it. So what pulls Down to the Bone up from the dreck of all the other indie druggie movies? Simply put, one element: Vera Farmiga in a performance of such guts and vision that it justly won her the Los Angeles Film Critics’ Best Actress prize.

Unlike many of her peers, Farmiga’s take on a highly-functioning junkie is one of subtle grace. Watching Irene is like watching the world’s most exhausted thief pull a job night after night. She knows she’s doing something wrong—a trigger pulled by the near-constant presence of her children—but she can’t stop. Watching Irene is like watching the world’s most exhausted thief pull a job over and over again, night after night.., That brand of cringe-inducing self-awareness makes the viewer feel like she feels like she’ll get caught eventually, whether by her boss, sponsor, or the police, and she’s just stealing as much time as she can before it happens. You keep waiting for the breakdown. The emotional outburst all Hollywood drug addicts reach after the worst has happened—usually running out of drugs. Yet Farmiga refuses to go there. She doesn’t want to take the easy way out, even if the story surrounding her (perhaps) does in certain respects. Instead, Farmiga crafts an indelible and original model of addiction for generations of her peers to imitate—the silent sufferer.

Some may dismiss the movie (as most mainstream audiences did) and Farmiga because both are so laid back, too-natural almost. It’s fitting and, when you think about it, fierce. She makes Down to the Bone worth looking up.

-Matt Mazur and Ben Travers

Hunger (2008)

THE DARK SIDE

Michael Fassbender

In Hunger, Steve McQueen’s elliptical, brutal, and utterly devastating 2008 film about the martyring of Irishman Bobby Sands (among others) to the cause of republicanism in 1981, Michael Fassbender turns in one of recent cinema’s most astounding performances. Playing (but one wants to say inhabiting) one of the most famous figures in the long and bloody history of the Troubles, Fassbender breathes into Sands an emotional sensitivity, a wiry electricity, and an intellectual complexity that radiates and compels. This is one of the toughest films of the past few years, one of the hardest pictures to sit through.

Indeed, McQueen’s approach to this harrowing subject—a hunger strike among Irish Republican Army political prisoners amid the deplorable conditions in the Maze, their British-run penitentiary, which leaves ten of them, including Sands, finally, dead—is a stunningly intricate combination of dialogue-heavy vérité, dream-like visions, and sudden, tortuous violence. This oscillation between sudden, graphic brutality, dreamy meditations, and lengthy periods of utter calm (even boredom) suggests the mundane reality of life in lock down; this is a slow, tedious way to live. And to die.

The centerpiece of the film, and surely the most extraordinary bit of work in Fassbender’s already pretty extraordinary career, is the nearly 20-minute dialogue between his emaciated, shirtless, Bobby Sands and a brilliant, but cautious priest played by Liam Cunningham. As they sit facing each other across a cafeteria table, cigarette smoke rising and swirling around them both, they talk. And talk. Cunningham’s priest pushes Sands to see that this hunger strike is cynical, pointless; to choose to destroy one’s body is not heroic, but rather an affront to God, to life itself.

Fassbender’s Sands counters with a knockout punch: a lengthy monologue, shot in a single take in roughly five uninterrupted minutes, in which he recounts a childhood incident in which he and some other kids found an injured foal suffering in its agony. While the other boys debated what to do, stalling as the foal bled and writhed, he bent down and put it out of its misery. An act of mercy, despite his knowledge that he would be punished, perhaps severely, for this act by a nearby priest who, having spied them, was shouting for him to stop. “But I know I did the right thing by that wee foal”, he says, Fassbender’s eyes blazing. “And I could take the punishment for all our boys.”

-Stuart Henderson

Michael Fassbender

In Hunger, Steve McQueen’s elliptical, brutal, and utterly devastating 2008 film about the martyring of Irishman Bobby Sands (among others) to the cause of republicanism in 1981, Michael Fassbender turns in one of recent cinema’s most astounding performances. Playing (but one wants to say inhabiting) one of the most famous figures in the long and bloody history of the Troubles, Fassbender breathes into Sands an emotional sensitivity, a wiry electricity, and an intellectual complexity that radiates and compels. This is one of the toughest films of the past few years, one of the hardest pictures to sit through.

Indeed, McQueen’s approach to this harrowing subject—a hunger strike among Irish Republican Army political prisoners amid the deplorable conditions in the Maze, their British-run penitentiary, which leaves ten of them, including Sands, finally, dead—is a stunningly intricate combination of dialogue-heavy vérité, dream-like visions, and sudden, tortuous violence. This oscillation between sudden, graphic brutality, dreamy meditations, and lengthy periods of utter calm (even boredom) suggests the mundane reality of life in lock down; this is a slow, tedious way to live. And to die.

The centerpiece of the film, and surely the most extraordinary bit of work in Fassbender’s already pretty extraordinary career, is the nearly 20-minute dialogue between his emaciated, shirtless, Bobby Sands and a brilliant, but cautious priest played by Liam Cunningham. As they sit facing each other across a cafeteria table, cigarette smoke rising and swirling around them both, they talk. And talk. Cunningham’s priest pushes Sands to see that this hunger strike is cynical, pointless; to choose to destroy one’s body is not heroic, but rather an affront to God, to life itself.

Fassbender’s Sands counters with a knockout punch: a lengthy monologue, shot in a single take in roughly five uninterrupted minutes, in which he recounts a childhood incident in which he and some other kids found an injured foal suffering in its agony. While the other boys debated what to do, stalling as the foal bled and writhed, he bent down and put it out of its misery. An act of mercy, despite his knowledge that he would be punished, perhaps severely, for this act by a nearby priest who, having spied them, was shouting for him to stop. “But I know I did the right thing by that wee foal”, he says, Fassbender’s eyes blazing. “And I could take the punishment for all our boys.”

-Stuart Henderson

JxSxPx's rating:

FROM PAGE TO SCREEN

Jane Fonda

You’ve got to hand it to Jane Fonda. She started her movie career fifty years ago as the daughter of America’s hero, and has weathered controversy, a dump truck full of hits and flops, and even blacklisting. And now? Well, she’s still as charming and relevant as ever. Her new film, Peace, Love, and Misunderstanding, shows that she can take so-so writing and an almost unthinkably unplayable character, look at her squarely, with almost pathological empathy and—voila!—she becomes the latest progression in her long legacy of playing fascinating women that reflect her own equally fascinating personal journey.

But let’s turn back to where it all began. Her first major success as a dramatic actress came with the unforgettable They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? The setting: an auditorium in Depression-era Santa Monica. A big gang of contestants sign up to dance non-stop for as long as it takes in order to win a paltry cash prize. You’d expect these poor souls to crash after a few hours, but no. They hold on for weeks and weeks, getting more desperate and losing touch with reality. Human ambition grows stronger than the body. The film was originally promoted with the tagline “people are the ultimate spectacle”, and the proto-reality television misery that stems from a consuming desire for easy fame underlines this at every turn of the film, but especially in Fonda’s wounded performance.

As Gloria, a would-be actress who is woeful and down-on-her-luck, Fonda runs an incredible gamut of emotions. She dances day and night with her substitute parter Robert, and they draw their strength from one another when Huston they’re not sleeping on each other’s shoulders. Her confidence is unwavering. At one point, the exhausted contestants must run in a derby designed to eliminate the weakest dancers. When one man has a heart attack, Gloria picks him up and carries his limp, old body across the finish line. Fonda, covered in sweat, with her make-up smeared and her dresses dirty, forgoes the slightest trace of 30’s glamour. Instead, she’s more like a depressed Tennessee Williams heroine crossed with an action star. Her sadness is her starter fluid and watching Gloria ignite and flame out like a spectacular pyrotechnic effect is agonizing as Fonda unsparingly plays this character as a woman hopelessly trapped in a burning building, dancing her life away.

-AD

Jane Fonda

You’ve got to hand it to Jane Fonda. She started her movie career fifty years ago as the daughter of America’s hero, and has weathered controversy, a dump truck full of hits and flops, and even blacklisting. And now? Well, she’s still as charming and relevant as ever. Her new film, Peace, Love, and Misunderstanding, shows that she can take so-so writing and an almost unthinkably unplayable character, look at her squarely, with almost pathological empathy and—voila!—she becomes the latest progression in her long legacy of playing fascinating women that reflect her own equally fascinating personal journey.

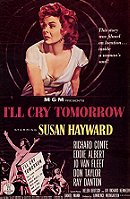

But let’s turn back to where it all began. Her first major success as a dramatic actress came with the unforgettable They Shoot Horses, Don’t They? The setting: an auditorium in Depression-era Santa Monica. A big gang of contestants sign up to dance non-stop for as long as it takes in order to win a paltry cash prize. You’d expect these poor souls to crash after a few hours, but no. They hold on for weeks and weeks, getting more desperate and losing touch with reality. Human ambition grows stronger than the body. The film was originally promoted with the tagline “people are the ultimate spectacle”, and the proto-reality television misery that stems from a consuming desire for easy fame underlines this at every turn of the film, but especially in Fonda’s wounded performance.