Tarkovsky (feature films) ranked

Sort by:

Showing 7 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

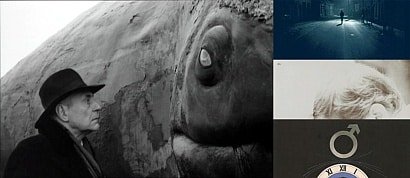

The son of a celebrated poet quoted in his films, Andrei Tarkovsky was born in 1932, in the Volga countryside not far from Moscow. He studied film under the influential Mikhail Romm. Undoubtedly the most important post-war Russian director, his status has been recognised in a range of international festivals and polls - Andrei Rublev, Mirror and Stalker in particular are regulars in critics' top 10s.

Tarkovsky's feature-length debut, Venice Golden Lion winner Ivan's Childhood (1962) is an accessible, welcoming introduction to the lustrous, ethereal landscapes and major themes (dreams and memories, freedom, childlike faith, home and absence from it) which characterise his career. A particular favourite of the late Krzysztof Kieslowski, its touching story of a young World War 2 scout makes for a more lyrical companion to Elem Klimov's harrowing Come and See (1985)

Completed in 1966 but delayed for several years by the Soviet authorities, the towering episodic epic Andrei Rublev stands not only as the most convincing portrait of the middle ages but with its ambitious scope, astounding set pieces and glorious colour finale -icons almost burst the screen- as a prime contender for the coveted title of "greatest film".

If the sometimes ponderous ruminations of Solaris (1972), a striking space odyssey inappropriately pigeon-holed as a socialist riposte to 2001, hint that Tarkovsky's mysticism may be better suited to Earth, it nevertheless has many fervent admirers. Notably, and typically for Tarkovsky, it looks back towards earth and home. For Mark le Fanu, author of a fine book on the director, it is a "majestic and achieved work of art", though the director himself was less satisfied.

At the centre of his oeuvre, the fathomless, almost cubist, personal and panoramic Mirror (1974) fully justifies Chris Peachment's exhortation to "see it above all for a series of images of such luminous beauty that they will make your heart burst". The sustained, ecstatic concentration of its poetry is unmatched. Once roundly condemned at home for obscurity, its reputation now rivals that of Andrei Rublev.

Stalker (1979) is an equally mesmerising experience: transcending its grim industrial setting, eerie, hallucinatory visions accompany the lugubrious trio- a writer, a scientist and their guide- who venture into its reality-altering radioactive Zone

Reputedly only denied the 1983 Cannes Palme d'Or by the machinations of Sergei Bondarchuk, Nostalgia concerns the awkward relationship between a Soviet professor researching in Italy and his pretty interpreter. A year before Tarkovsky asserted his artistic independence by voluntary exile in the West, its shimmering reveries already ache with homesick longing: never has a fog-bound Tuscany seemed so resolutely Russian.

By the time of his final film, set on a desolate stretch of Swedish coast, he was dying of cancer. Typically uncompromising in its pacing and anti-nuclear message, The Sacrifice (1986) is a stately, disdainfully imperious achievement. Enhanced by the masterful long-take cinematography of (Bergman regular) Nykvist, it is worth seeing for its opening sequence alone.

The director's serious moral concerns and probing scrutiny of spiritual malaise have inevitably prompted comparisons with Bergman, an admirer who proclaimed him "the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream".

For all its Northern melancholy, Tarkovsky's cinema resonates with a radiant, redemptive optimism. In Andrei Rublev, the atrocity-haunted artist breaks his silence in wonderment at a novice bell-maker's leap of faith. Mirror begins with the remarkable curing of a stutter and Stalker ends, not in enveloping despair, but with Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" and a disabled young girl's telepathic movement of three glasses. In The Sacrifice, nuclear holocaust is averted by a seemingly mad religious conviction, while the single most abiding image is of a boy planting a tree. The quite astonishing visual and aural imagery (rain, mist, fire, wind and grass rendered unmistakeably, inimitably "Tarkovskian") repeatedly makes the mundane miraculous, everyday elements and objects divine. And through Faith humankind can literally take flight.

With all seven features currently available, the auteur's rapturous, challenging, complex world - of witches, Tatar hordes, horses, mysterious stray dogs, forests, rivers, meadows, Brueghelesque snowscapes, Renaissance paintings, balloons, space stations and levitation - can be studied and enjoyed at leisure. "Blazing with posthumous light", this unique set of films is ideal for collection.

Tarkovsky's feature-length debut, Venice Golden Lion winner Ivan's Childhood (1962) is an accessible, welcoming introduction to the lustrous, ethereal landscapes and major themes (dreams and memories, freedom, childlike faith, home and absence from it) which characterise his career. A particular favourite of the late Krzysztof Kieslowski, its touching story of a young World War 2 scout makes for a more lyrical companion to Elem Klimov's harrowing Come and See (1985)

Completed in 1966 but delayed for several years by the Soviet authorities, the towering episodic epic Andrei Rublev stands not only as the most convincing portrait of the middle ages but with its ambitious scope, astounding set pieces and glorious colour finale -icons almost burst the screen- as a prime contender for the coveted title of "greatest film".

If the sometimes ponderous ruminations of Solaris (1972), a striking space odyssey inappropriately pigeon-holed as a socialist riposte to 2001, hint that Tarkovsky's mysticism may be better suited to Earth, it nevertheless has many fervent admirers. Notably, and typically for Tarkovsky, it looks back towards earth and home. For Mark le Fanu, author of a fine book on the director, it is a "majestic and achieved work of art", though the director himself was less satisfied.

At the centre of his oeuvre, the fathomless, almost cubist, personal and panoramic Mirror (1974) fully justifies Chris Peachment's exhortation to "see it above all for a series of images of such luminous beauty that they will make your heart burst". The sustained, ecstatic concentration of its poetry is unmatched. Once roundly condemned at home for obscurity, its reputation now rivals that of Andrei Rublev.

Stalker (1979) is an equally mesmerising experience: transcending its grim industrial setting, eerie, hallucinatory visions accompany the lugubrious trio- a writer, a scientist and their guide- who venture into its reality-altering radioactive Zone

Reputedly only denied the 1983 Cannes Palme d'Or by the machinations of Sergei Bondarchuk, Nostalgia concerns the awkward relationship between a Soviet professor researching in Italy and his pretty interpreter. A year before Tarkovsky asserted his artistic independence by voluntary exile in the West, its shimmering reveries already ache with homesick longing: never has a fog-bound Tuscany seemed so resolutely Russian.

By the time of his final film, set on a desolate stretch of Swedish coast, he was dying of cancer. Typically uncompromising in its pacing and anti-nuclear message, The Sacrifice (1986) is a stately, disdainfully imperious achievement. Enhanced by the masterful long-take cinematography of (Bergman regular) Nykvist, it is worth seeing for its opening sequence alone.

The director's serious moral concerns and probing scrutiny of spiritual malaise have inevitably prompted comparisons with Bergman, an admirer who proclaimed him "the greatest, the one who invented a new language, true to the nature of film, as it captures life as a reflection, life as a dream".

For all its Northern melancholy, Tarkovsky's cinema resonates with a radiant, redemptive optimism. In Andrei Rublev, the atrocity-haunted artist breaks his silence in wonderment at a novice bell-maker's leap of faith. Mirror begins with the remarkable curing of a stutter and Stalker ends, not in enveloping despair, but with Beethoven's "Ode to Joy" and a disabled young girl's telepathic movement of three glasses. In The Sacrifice, nuclear holocaust is averted by a seemingly mad religious conviction, while the single most abiding image is of a boy planting a tree. The quite astonishing visual and aural imagery (rain, mist, fire, wind and grass rendered unmistakeably, inimitably "Tarkovskian") repeatedly makes the mundane miraculous, everyday elements and objects divine. And through Faith humankind can literally take flight.

With all seven features currently available, the auteur's rapturous, challenging, complex world - of witches, Tatar hordes, horses, mysterious stray dogs, forests, rivers, meadows, Brueghelesque snowscapes, Renaissance paintings, balloons, space stations and levitation - can be studied and enjoyed at leisure. "Blazing with posthumous light", this unique set of films is ideal for collection.

Added to

Related lists

20 From 70. My Favorite Films From The Year 1970

20 item list by The Mighty Celestial

13 votes 2 comments

2 comments

20 item list by The Mighty Celestial

13 votes

2 comments

2 comments

35 From 00: My Favorite Films From The Year 2000

35 item list by The Mighty Celestial

6 votes 1 comment

1 comment

35 item list by The Mighty Celestial

6 votes

1 comment

1 comment

View more top voted lists

People who voted for this also voted for

My beginning vinyl collection

The warmth of Hirokazu Koreeda

KRZYSZTOF KIESLOWSKI 10 favorite movies

Cosmic Consciousness by Richard Maurice Bucke

Album covers I like

ANDREI TARKOVSKY 10 favorites movies

Western Movie Posters: Jack Hoxie

Hollywood's Greatest Villains!

Stunning Bridal Makeup by Makeup Artist Nasreen..

Tom Petty and The Heartbreakers: Discography

Girlie Movies That I Like

Spiritual Choices (religions and philosophies)

Listal SciFi: Themed Book Lists

Movies with Religion from Superant

History Learning

More lists from Kenji

My Favourite Hungarian Films

My Music lists

Beautiful Bhutan

My Favourite Classical Composers

Great rivers: the Mekong

A Woody Allen selection (with quotes)

The Best of Jean Renoir

Login

Login

784

784

8.3

8.3

7.9

7.9