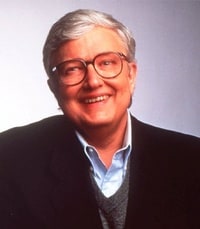

Roger Ebert didn't like all the Classics

Sort by:

Showing 41 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

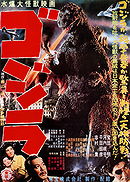

Godzilla (1954)

His Review :

Regaled for 50 years by the stupendous idiocy of the American version of "Godzilla," audiences can now see the original Japanese version, which is equally idiotic, but, properly decoded, was the "Fahrenheit 9/11" of its time. Both films come after fearsome attacks on their nations, embody urgent warnings, and even incorporate similar dialogue, such as "The report is of such dire importance it must not be made public." Is that from 1954 Tokyo or 2004 Washington?

The first "Godzilla" set box office records in Japan and inspired countless sequels, remakes and rip-offs. It was made shortly after an American H-bomb test in the Pacific contaminated a large area of ocean and gave radiation sickness to a boatload of Japanese fishermen. It refers repeatedly to Nagasaki, H-bombs and civilian casualties, and obviously embodies Japanese fears about American nuclear tests.

The military battles Godzilla as the monster terrorizes the citizens of Tokyo in this scene from the 1954 Japanese film version of "Godzilla.

(Enlarge Image)But that is not the movie you have seen. For one thing, it doesn't star Raymond Burr as Steve Martin, intrepid American journalist, who helpfully explains, "I was headed for an assignment in Cairo when I dropped off for a social call in Tokyo."

In the '50s, the American producer Joseph E. Levine bought the Japanese film, cut it by 40 minutes, removed all of the political content, and awkwardly inserted Burr into scenes where he clearly did not fit. The hapless actor gives us reaction shots where he's looking in the wrong direction, listens to Japanese actors dubbed into the American idiom (they always call him, "Steve Martin" or even "the famous Steve Martin"), and provides a reassuring conclusion in which Godzilla is seen as some kind of public health problem, or maybe just a malcontent.

The Japanese version, now in general U.S. release to mark the film's 50th anniversary, is a bad film, but with an undeniable urgency. I learn from helpful notes by Mike Flores of the Psychotronic Film Society that the opening scenes, showing fishing boats disappearing as the sea boils up, would have been read by Japanese audiences as a coded version of U.S. underwater H-bomb tests. Much is made of a scientist named Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), who could destroy Godzilla with his secret weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer, but hesitates because he is afraid the weapon might fall into the wrong hands, just as H-bombs might, and have. The film's ending warns that atomic tests may lead to more Godzillas. All cut from the U.S. version.

In these days of flawless special effects, Godzilla and the city he destroys are equally crude. Godzilla at times looks uncannily like a man in a lizard suit, stomping on cardboard sets, as indeed he was, and did. Other scenes show him as a stuffed, awkward animatronic model. This was not state of the art even at the time; "King Kong" (1933) was much more convincing.

When Dr. Serizawa demonstrates the Oxygen Destroyer to the fiancee of his son, the superweapon is somewhat anticlimactic. He drops a pill into a tank of tropical fish, the tank lights up, he shouts "stand back!," the fiancee screams, and the fish go belly up. Yeah, that'll stop Godzilla in his tracks.

Reporters covering Godzilla's advance are rarely seen in the same shot with the monster. Instead, they look offscreen with horror; a TV reporter, broadcasting for some reason from his station's tower, sees Godzilla looming nearby and signs off, "Sayonara, everyone!" Meanwhile, searchlights sweep the sky, in case Godzilla learns to fly.

The movie's original Japanese dialogue, subtitled, is as harebrained as Burr's dubbed lines. When the Japanese Parliament meets (in what looks like a high school home room), the dialogue is portentous but circular:

"The professor raises an interesting question! We need scientific research!"

"Yes, but at what cost?"

"Yes, that's the question!"

Is there a reason to see the original "Godzilla"? Not because of its artistic stature, but perhaps because of the feeling we can sense in its parable about the monstrous threats unleashed by the atomic age. There are shots of Godzilla's victims in hospitals, and they reminded me of documentaries of Japanese A-bomb victims. The incompetence of scientists, politicians and the military will ring a bell.

This is a bad movie, but it has earned its place in history, and the enduring popularity of Godzilla and other monsters shows that it struck a chord. Can it be a coincidence, in these years of trauma after 9/11, that in a 2005 remake, King Kong will march once again on New York?

His Rating :

suggested by AVPGuyver21

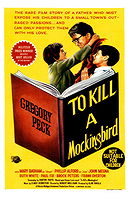

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

His Review :

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is a time capsule, preserving hopes and sentiments from a kinder, gentler, more naive America. It was released in December 1962, the last month of the last year of the complacency of the postwar years. The following November, John F. Kennedy would be assassinated. Nothing would ever be the same again -- not after the deaths of Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, not after the war in Vietnam, certainly not after September 11, 2001. The most hopeful development during that period for America was the civil rights movement, which dealt a series of legal and moral blows to racism. But "To Kill a Mockingbird," set in Maycomb, Alabama, in 1932, uses the realities of its time only as a backdrop for the portrait of a brave white liberal.

The movie has remained the favorite of many people. It is currently listed as the 29th best film of all time in a poll by the Internet Movie Database. Such polls are of questionable significance, but certainly the movie and the Harper Lee novel on which it is based have legions of admirers. It is being read by many Chicagoans as part of a city-wide initiative in book discussion. It is a beautifully-written book, but it should be used not as a record of how things are, or were, but of how we once liked to think of them.

The novel, which focuses on the coming of age of three young children, especially the tomboy Scout, gains strength from her point of view: It sees the good and evil of the world through the eyes of a six-year-old child. The movie shifts the emphasis to the character of her father, Atticus Finch, but from this new point of view doesn't see as much as an adult in that time and place should see.

Maycomb is evoked by director Robert Mulligan as a "tired old town" of dirt roads, picket fences, climbing vines, front porches held up by pillars of brick, rocking chairs, and Panama hats. Scout (Mary Badham) and her 10-year-old brother Jem (Philip Alford) live with their widowed father Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) and their black housekeeper Calpurnia (Estelle Evans). They make friends with a new neighbor named "Dill" Harris (John Megna), who wears glasses, speaks with an expanded vocabulary, is small for his age, and is said to be inspired by Harper Lee's childhood friend Truman Capote. Atticus goes off every morning to his law office downtown, and the children play through lazy hot days.

Their imagination is much occupied by the Radley house, right down the street, which seems always dark, shaded and closed. Jem tells Dill that Mr. Radley keeps his son Boo chained to a bed in the house, and describes Boo breathlessly: "Judging from his tracks, he's about six and a half feet tall. He eats raw squirrels and all the cats he can catch. There's a long, jagged scar that runs all the way across his face. His teeth are yellow and rotten. His eyes are popped. And he drools most of the time." Of course the first detail reveals Jem has never seen Boo.

Into this peaceful calm drops a thunderbolt. Atticus is asked by the town judge to defend a black man named Tom Robinson (Brock Peters), who has been accused of raping a poor white girl named Mayella Violet Ewell (Collin Wilcox). White opinion is of course much against the black man, who is presumed guilty, and Mayelle's father Bob (James Anderson) pays an ominous call on Atticus, indirectly threatening his children. The children are also taunted at school, and get in fights; Atticus explains to them why he is defending a Negro, and warns them against using the word "nigger."

The courtroom scenes are the most celebrated in the movie; they make it perfectly clear that Tom Robinson is innocent, that no rape occurred, that Maybelle came on to Robinson, that he tried to flee, that Bob Ewell beat his own daughter, and she lied about it out of shame for feeling attracted to a black man. Atticus' summation to the jury is one of Gregory Peck's great scenes, but of course the all-white jury finds Tom Robinson guilty anyway. The verdict is greeted by an uncanny quiet: No whoops of triumph from Bob Ewell, no cries of protests by the blacks in the courtroom gallery. The whites file out quickly, but the blacks remain and stand silently in honor of Atticus as he walks out a little later. Scout and her brother sat up with the blacks throughout the trial, and now a minister tells her: "Miss Jean Louise, stand up, your father's passin'."

The problem here, for me, is that the conviction of Tom Robinson is not the point of the scene, which looks right past him to focus on the nobility of Atticus Finch. I also wonder at the general lack of emotion in the courtroom, and the movie only grows more puzzling by what happens next. Atticus is told by the sheriff that while Tom Robinson was being taken for safekeeping to nearby Abbottsville, he broke loose and tried to run away. As Atticus repeats the story: "The deputy called out to him to stop. Tom didn't stop. He shot at him to wound him and missed his aim. Killed him. The deputy says Tom just ran like a crazy man."

That Scout could believe it happened just like this is credible. That Atticus Finch, an adult liberal resident of the Deep South in 1932, has no questions about this version is incredible. In 1962 it is possible that some (white) audiences would believe that Tom Robinson was accidentally killed while trying to escape, but in 2001 such stories are met with a weary cynicism.

The construction of the following scene is highly implausible. Atticus drives out to Tom Robinson's house to break the sad news to his widow, Helen. She is played by Kim Hamilton (who is not credited, and indeed has no speaking lines in a film that finds time for dialog by two superfluous white neighbors of the Finches). On the porch are several male friends and relatives. Bob Ewell, the vile father who beat his girl into lying, lurches out of the shadows and says to one of them, "Boy, go in the house and bring out Atticus Finch." One of the men does so, Ewell spits in Atticus's face, Atticus stares him down and drives away. The black people in this scene are not treated as characters, but as props, and kept entirely in long shot. The close-ups are reserved for the white hero and villain.

It may be that in 1932 the situation was such in Alabama that this white man, who the people on that porch had seen lie to convict Tom Robinson, could walk up to them alone after they had just learned he had been killed, call one of them "boy," and not be touched. If black fear of whites was that deep in those days, then the rest of the movie exists in a dream world.

The upbeat payoff involves Ewell's cowardly attack on Scout and Jem, and the sudden appearance of the mysterious Boo Radley (Robert Duvall, in his first screen performance), to save them. Ewell is found dead with a knife under his ribs. Boo materializes inside the Finch house, is identified by Scout as her savior, and they're soon sitting side by side on the front porch swing. The sheriff decides that no good would be served by accusing Boo of the death of Ewell. That would be like "killing a mockingbird," and we know from earlier in the film that you can shoot all the bluejays you want, but not mockingbirds -- because all they do is sing to bring music to the garden. Not exactly a description of the silent Boo Radley, but we get the point.

This is a tricky note to end on, because it brings Boo Radley in literally from the wings as a distraction from the facts: An innocent black man was framed for a crime that never took place, he was convicted by a white jury in the face of overwhelming evidence, and he was shot dead in problematic circumstances. Now we are expected to feel good because the events got Boo out of the house. That Boo Radley killed Bob Ewell may be justice, but it is not parity. The sheriff says, "There's a black man dead for no reason, and now the man responsible for it is dead. Let the dead bury the dead this time." But I doubt that either Tom Robinson or Bob Ewell would want to be buried by the other.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is, as I said, a time capsule. It expresses the liberal pieties of a more innocent time, the early 1960s, and it goes very easy on the realities of small-town Alabama in the 1930s. One of the most dramatic scenes shows a lynch mob facing Atticus, who is all by himself on the jailhouse steps the night before Tom Robinson's trial. The mob is armed and prepared to break in and hang Robinson, but Scout bursts onto the scene, recognizes a poor farmer who has been befriended by her father, and shames him (and all the other men) into leaving. Her speech is a calculated strategic exercise, masked as the innocent words of a child; one shot of her eyes shows she realizes exactly what she's doing. Could a child turn away a lynch mob at that time, in that place? Isn't it nice to think so.

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

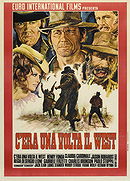

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

His Review :

Sergio Leone's "Once Upon a Time in the West" is a painstaking distillation of the style he made famous in the original three Clint Eastwood Westerns. There's the same eerie music; the same sweaty, ugly faces; the same rhythm of waiting and violence; the same attention to small details of Western life.

There is also, unfortunately, Leone's inability to call it quits. The movie stretches on for nearly three hours, with intermission, and provides two false alarms before it finally ends. In between, we're given a plot complex enough for Antonioni, involving killers, land rights, railroads, long-delayed revenge, mistaken identity, love triangles, double-crosses and shoot-outs. We're well into the second hour of the movie before the plot becomes quite clear.

These difficulties notwithstanding, "Once Upon a Time in the West" is good fun, especially if you like Leone's way of savoring the last morsel of every scene. A final shoot-out between Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson, for example, takes at least 15 minutes. They walk. They wait. They circle each other. They stare at each other. They squint. They spit. They take off their jackets. They wince. Just when they finally seem prepared to shoot after all, Leone uses a flashback. But why hurry a good shoot-out?

Leone's first two "spaghetti Westerns" ("A Fistful of Dollars," "For a Few Dollars More") were made with small budgets. His third, "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly," was made with a few dollars more. But this one was bankrolled by Paramount and looks like it: There's a wealth of detail, a lot of extras, elaborate sets. There's a sense of the life of the West going on all around the action (and that sense is impossible to obtain on small budgets).

Leone produces some interesting performances by casting against type. Henry Fonda is the bad guy for once in his career; Charles Bronson is impressively inscrutable as the mysterious good guy; and Jason Robards is a tough guy, believe it or not. Claudia Cardinale was a good choice for the woman, but Leone directs her too passively; in "Cartouche," she demonstrated a blood-and-thunder abandon that's lacking here.

His Rating :

suggested by thenoah

johanlefourbe's rating:

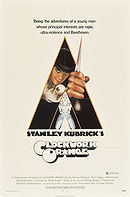

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

His Review :

Stanley Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange" is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading As an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex.

I don't know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom Kubrick likes very much, as his visual style reveals and as we shall see in a moment). Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we've all run across a few times in our lives -- usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies. He must have been the kind of kid who tore off the wings of flies and ate ants just because that was so disgusting. He was the kid who always seemed to know more about sex than anyone else, too -- and especially about how dirty it was.

Alex has grown up in "A Clockwork Orange," and now he's a sadistic rapist. I realize that calling him a sadistic rapist -- just like that -- is to stereotype poor Alex a little. But Kubrick doesn't give us much more to go on, except that Alex likes Beethoven a lot. Why he likes Beethoven is never explained, but my notion is that Alex likes Beethoven in the same way that Kubrick likes to load his sound track with familiar classical music -- to add a cute, cheap, dead-end dimension.

Now Alex isn't the kind of sat-upon, working-class anti-hero we got in the angry British movies of the early 1960s. No effort is made to explain his inner workings or take apart his society. Indeed, there's not much to take apart; both Alex and his society are smart-nose pop-art abstractions. Kubrick hasn't created a future world in his imagination -- he's created a trendy decor. If we fall for the Kubrick line and say Alex is violent because "society offers him no alternative," weep, sob, we're just making excuses.

Alex is violent because it is necessary for him to be violent in order for this movie to entertain in the way Kubrick intends. Alex has been made into a sadistic rapist not by society, not by his parents, not by the police state, not by centralization and not by creeping fascism -- but by the producer, director and writer of this film, Stanley Kubrick. Directors sometimes get sanctimonious and talk about their creations in the third person, as if society had really created Alex. But this makes their direction into a sort of cinematic automatic writing. No, I think Kubrick is being too modest: Alex is all his.

I say that in full awareness that "A Clockwork Orange" is based, somewhat faithfully, on a novel by Anthony Burgess. Yet I don't pin the rap on Burgess. Kubrick has used visuals to alter the book's point of view and to nudge us toward a kind of grudging pal-ship with Alex.

Kubrick's most obvious photographic device this time is the wide-angle lens. Used on objects that are fairly close to the camera, this lens tends to distort the sides of the image. The objects in the center of the screen look normal, but those on the edges tend to slant upward and outward, becoming bizarrely elongated. Kubrick uses the wide-angle lens almost all the time when he is showing events from Alex's point of view; this encourages us to see the world as Alex does, as a crazy-house of weird people out to get him.

When Kubrick shows us Alex, however, he either places him in the center of a wide-angle shot (so Alex alone has normal human dimensions,) or uses a standard lens that does not distort. So a visual impression is built up during the movie that Alex, and only Alex, is normal.

Kubrick has another couple of neat gimmicks to build Alex into a hero instead of a wretch. He likes to shoot Alex from above, letting Alex look up at us from under a lowered brow. This was also a favorite Kubrick angle in the close-ups in "2001: A Space Odyssey," and in both pictures, Kubrick puts the lighting emphasis on the eyes. This gives his characters a slightly scary, messianic look.

And then Kubrick makes all sorts of references at the end of "A Clockwork Orange" to the famous bedroom (and bathroom) scenes at the end of "2001." The echoing water-drips while Alex takes his bath remind us indirectly of the sound effects in the "2001" bedroom, and then Alex sits down to a table and a glass of wine. He is photographed from the same angle Kubrick used in "2001" to show us Keir Dullea at dinner. And then there's even a shot from behind, showing Alex turning around as he swallows a mouthful of wine.

This isn't just simple visual quotation, I think. Kubrick used the final shots of "2001" to ease his space voyager into the Space Child who ends the movie. The child, you'll remember, turns large and fearsomely wise eyes upon us, and is our savior. In somewhat the same way, Alex turns into a wide eyed child at the end of "A Clockwork Orange," and smiles mischievously as he has a fantasy of rape. We're now supposed to cheer because he's been cured of the anti-rape, anti-violence programming forced upon him by society during a prison "rehabilitation" process.

What in hell is Kubrick up to here? Does he really want us to identify with the antisocial tilt of Alex's psychopathic little life? In a world where society is criminal, of course, a good man must live outside the law. But that isn't what Kubrick is saying, He actually seems to be implying something simpler and more frightening: that in a world where society is criminal, the citizen might as well be a criminal, too.

Well, enough philosophy. We'll probably be debating "A Clockwork Orange" for a long time -- a long, weary and pointless time. The New York critical establishment has guaranteed that for us. They missed the boat on "2001," so maybe they were trying to catch up with Kubrick on this one. Or maybe the news weeklies just needed a good movie cover story for Christmas.

I don't know. But they've really hyped "A Clockwork Orange" for more than it's worth, and a lot of people will go if only out of curiosity. Too bad. In addition to the things I've mentioned above -- things I really got mad about -- "A Clockwork Orange" commits another, perhaps even more unforgivable, artistic sin. It is just plain talky and boring. You know there's something wrong with a movie when the last third feels like the last half.

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

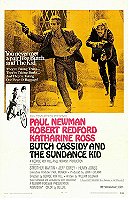

His Review :

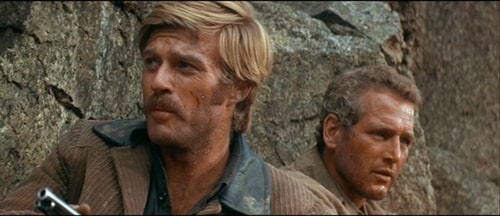

"Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid" must have looked like a natural on paper, but, alas, the completed film is slow and disappointing. This despite the fact that it contains several good laughs and three sound performances.

The problems are two. First, the investment in superstar Paul Newman apparently inspired a bloated production that destroys the pacing. Second, William Goldman's script is constantly too cute and never gets up the nerve, by God, to admit it's a Western.

The premise was promising. Butch (Newman) and Sundance (Robert Redford) were two Western outlaws (unsung until now) who led a gang of cutthroat train robbers. But when Harriman, the railroad tycoon, got up a special posse of experts to hunt them, they lit out for Bolivia and stuck up banks there. You can see, in "Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid," the bones of the good movie that could have been made about them.

But unfortunately, this good movie is buried beneath millions of dollars that were spent on "production values" that wreck the show. This is often the fate of movies with actors in the million-dollar class, like Newman. Having invested all that cash in the superstar, the studio gets nervous and decides to spend lots of money to protect its investment.

That's what happened here. The movie starts promisingly, with an amusing period-piece newsreel about the Cassidy gang. And then there is a scene in a tavern where Sundance faces down a tough gambler, and that's good. And then a scene where Butch puts down a rebellion in his gang, and that's one of the best things in the movie. And then an extended bout of train-robbing, climaxing in a dynamite explosion that'll have you rolling in the aisles. And then we meet Sundance's girlfriend, played by Katharine Ross, and the scenes with the three of them have you thinking you've wandered into a really first-rate film.

But the trouble starts after Harriman hires his posse. It's called the Super-posse because it includes all the best lawmen and trackers in the West. When it approaches, the ground rumbles and we get the feeling it's a supernatural force. Butch and the Kid try to hide in the badlands, but the Super-posse cannot be fooled. It's always on their track. Forever.

Director George Roy Hill apparently spent a lot of money to take his company on location for these scenes, and I guess when he got back to Hollywood he couldn't bear to edit them out of the final version. So the Super-posse chases our heroes unceasingly, until we've long since forgotten how well the movie started and are desperately wondering if they'll ever get finished riding up and down those endless hills. And once bogged down, the movie never recovers.

It does show moments of promise, however, after Butch, the Kid and his girl go to Bolivia. There are some funny difficulties with Spanish, for example. But here the script throws us off. Goldman has his heroes saying such quick, witty and contemporary things that we're distracted: it's as if, in 1910, they were consciously speaking for the benefit of us clever 1969 types.

This dialog is especially inappropriate in the final shoot-out, when it gets so bad we can't believe a word anyone says. And then the violent, bloody ending is also a mistake; apparently it was a misguided attempt to copy "Bonnie and Clyde." But the ending doesn't belong on "Butch Cassidy," and we don't believe it, and we walk out of the theater wondering what happened to that great movie we were seeing until an hour ago.

His Rating :

suggested by Michael M

johanlefourbe's rating:

Straw Dogs (1971)

His Review :

Sam Peckinpah's "The Wild Bunch," one of the great movies of the decade, saw violence as essentially unselective. That was unusual in a Western, where violence has always been highly selective; with all those bullets flying around, you might get a good guy wounded once in a while, but somehow, mostly bad guys got killed.

The Western reflected our national view of violence, of foreign policy, of a lot of things. But Peckinpah seemed to be recasting it in a new mold, throwing out the moral extremes and stranding everyone in a gray, blood-soaked middle ground. In the shoot-out at the end of "The Wild Bunch," everyone caught it: men, women, children, dogs, chickens, regardless of guilt or innocence.

"The Wild Bunch" was attacked because of its nihilism, but I didn't see it that way. It seemed to me that Peckinpah was simply clearing away the moralistic oatmeal so we could see what was beneath the Western -- and beneath our regard for it.

For a long time, the old Hollywood production code required that justice be rewarded and evil punished (a requirement that inspired not a few bizarre endings for gangster movies). But even after the production code was junked, the Western still subscribed to it. We wanted it to.

Peckinpah was asking us not to kid ourselves, I thought. But now he comes along with "Straw Dogs," a major disappointment in which Peckinpah's theories about violence seem to have regressed to a sort of 19th-Century mixture of Kipling and machismo.

You have to understand, first of all, that the movie ends with maybe 20 minutes of unrestrained bloodletting, during which people are scalded with boiling whisky, have their feet blown off by shotguns, are clubbed to death and (in one case) nearly decapitated by a bear trap. The violence is the movie's reason for existing; it is the element that is being sold, and in today's movie market, It should sell well. But does Peckinpah pay his dues before the last 20 minutes? Does he keep us feeling we can trust him? I don't think so.

The movie is set in a British village apparently populated only by the movie's cast. This is a little unsettling, but we soon find that we don't need extras because the movie is going to be in close-up, and the close-ups are going to be of grotesque, melodramatic parodies, larger than life and smaller than cliche.

The movie's first shot is of children torturing a dog; the first shot of "The Wild Bunch" was of children torturing a scorpion. This has gotten to be Peckinpah's trademark, sort of his Leo the Lion, advertising his baleful opinion of the human prospect. A young American mathematician (Dustin Hoffman) comes to the village with his wife (Susan George), an English girl whose father owns a home there. They plan to make repairs and settle down while he gets on with his work. His work involves theory on the interiors of stars, but never mind; for Peckinpah's purposes he is an Intellectual.

That means of course that he lacks physical courage, can't mix freely with the local roughhouses, and manages by his every thought and deed to alienate all Good Old Boys everywhere. During one brief scene in the local pub, he manages to do no less than three terrible things: He orders "any kind of American cigarettes," he walks between a dart-player and his board and he buys a drink for the house but does not stay to have it. Such a boor deserves his comeuppance, and this being a Peckinpah universe, we somehow know it will involve rape and murder.

A gang of local handymen and layabouts come to fix the young couple's garage, and we learn that one of the men once went with the girl. He resents the American terribly, of course, and begins to taunt him in various ways. Their cat is hanged in the closet and things like that.

Meanwhile, Peckinpah is setting us up for the conclusion with a series of scenes that outdo anything Western Union has yet achieved with the telegraph. We meet the village idiot, a towering, blank-eyed chap who "made a mistake" once with a girl. We meet the town tart, who is a tight-sweatered tease. We learn that her father is the crudest man in the local pub. As sure as when Garbo coughs we know she's got TB, we know the idiot is going to go after the girl, and the brute is going to go after the idiot.

Through a series of melodramatic coincidences, the idiot winds up in the mathematician's barricaded house, while the lout and four or five drunken friends try to break in. They already have shot the magistrate dead, and now they demand the life of the idiot. Hoffman, taking a Moral Stand for once in his life, decides his home is his castle, etc. He figures out all the tricks like the boiling whisky.

The problem with this whole scene is that we have to believe the behavior of the men outside. They are drunk, and they are capable of total physical savagery without any thought of their own danger, it would appear. Getting into that house is worth their lives to them.

Well, the hard thing to believe is that anyone could get drunk enough to get into that state of frenzy and still be sober enough to do anything about it. One or two guys, maybe, But half a dozen? As they hurl themselves against Hoffman's barricades, we realize that everything is a setup to allow more variety in the violence.

And then the movie ends with the worst piece of pseudo-serious understatement since Peyton Place left the air. After Hoffman has killed them all, he drives the idiot back to the village.

"I don't know where I live," the idiot says.

"That's all right," says Hoffman, "neither do I."

What conclusions are we supposed to draw? That Hoffman achieved defeat in victory? That Peckinpah believes in the concept of a Just War? That drink drives men to the grave?

The most offensive thing about the movie is its hypocrisy; it is totally committed to the pornography of violence, but lays on the moral outrage with a shovel. The perfect criticism of "Straw Dogs" already has been made. It is "The Wild Bunch."

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

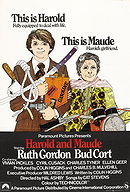

Harold and Maude (1971)

His Review :

Death can be as funny as most things in life, I suppose, but not the way Harold and Maude go about it. They meet because they're both funeral freaks, and one day their eyes lock over a grave. They fall into conversation after Maude steals Harold's hearse and offers him a ride. Harold drives a hearse, by the way, because he is fascinated by death, particularly his own. So fascinated that maybe the only reason he doesn't kill himself is that suicide would put an end to his suicide fantasies. You can see that Harold is a young man with a problem.

Now Maude, on the other hand, is seventy-nine years young, and has what is known in the trade as a lust for life. She lives in a railroad car, spends her afternoons uprooting city trees and returning them to the forest, and in general is an all-round booster of the life force. She goes to funerals because there is a time to live and a time to die, and she wants to be on time.

The word has gotten out that "Harold and Maude" is the story of a love affair between these two people. It is not, so necrophiliacs please stay cool. It is about how Harold annoys (yes, annoys would be the word) his mother by staging a staggering variety of suicide attempts. Let's see. There's immolation, hanging, whacking off his arm with a meat cleaver, driving his car over a cliff, drowning, and if I missed one, never mind. But his mother is merely annoyed. She takes a morning dip in the swimming pool, for example, and when she comes upon Harold's body floating face down, she merely swims another lap. Talk about exercise freaks.

Harold's mother figures maybe what Harold needs is a little female companionship. She signs him up with a computer dating service, but the girls are sort of put off when he sets himself afire on their date, and things like that. Maude, on the other hand, doesn't seem to mind. As played by Ruth Gordon, she is the same wise-cracking operator out of the side of the mouth that we met in "Rosemary's Baby." When a traffic cop stops her for being in possession of a stolen truck, a stolen car, and a stolen shovel, she apologizes and then drives away. When he catches up with her again, she steals his motorcycle. You see what an indomitable sort she is.

Harold is played by Bud Cort, the round-eyed and solemn-mouthed announcer over the PA system in "M*A*S*H." He is even rounder and more solemn this time, having perfected a funereal droop of the lower lip. It is hard to get very much animation into a character who is obsessed with his own oblivion, but Cort doesn't even try.

And so what we get, finally, is a movie of attitudes. Harold is death, Maude life, and they manage to make the two seem so similar that life's hardly worth the extra bother. The visual style makes everyone look fresh from the Wax Museum, and all the movie lacks is a lot of day-old gardenias and lilies and roses in the lobby, filling the place with a cloying sweet smell. Nothing more to report today. Harold doesn't even make pallbearer.

His Rating :

suggested by Mr. Saturn

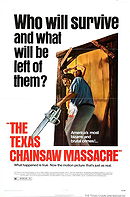

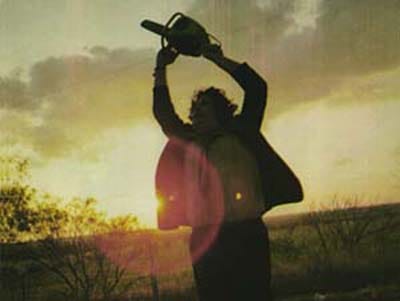

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974)

His Review :

Now here’s a grisly little item. “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” is as violent and gruesome and blood-soaked as the title promises -- a real Grand Guignol of a movie. It’s also without any apparent purpose, unless the creation of disgust and fright is a purpose. And yet in its own way, the movie is some kind of weird, off-the-wall achievement. I can’t imagine why anyone would want to make a movie like this, and yet it’s well-made, well-acted, and all too effective.

The movie’s based on factual material, according to the narration that opens it. For all I know, that’s true, although I can’t recall having heard of these particular crimes, and the distributor provides no documentation. Not that it matters. A true crime movie like Richard Brooks’ “In Cold Blood,” which studies the personalities and compulsions of two killers, dealt directly with documented material and was all the more effective for that. But “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” could have been made up from whole cloth without any apparent difference. No motivation, no background, no speculation on causes is evident anywhere in the film. It’s simply an exercise in terror.

It takes place in an isolated area of Texas, which five young people (one of them in a wheelchair) are driving through in their camper van. They pick up a weirdo hitchhiker who carries his charms and magic potions around his neck and who giggles insanely while he cuts himself on the hand and then slices at the paraplegic. They get rid of him, so they think.

But then they take a side trip to a haunted-looking old house, which some of them had been raised in. The two girls laugh as they clamber through the litter on the floor, but one of the guys notices some strange totems and charms which should give him warning. They don’t. He and his girlfriend set off for the old swimming hole, find it dried up, and then see a farmhouse nearby. The guy goes to ask about borrowing some gasoline and disappears inside.

His girl gets tired of waiting for him, knocks on the door, and disappears inside, too. A lot of people are going to be disappearing into this house, and its insides are a masterpiece of set decoration and the creation of mood. We see the innocent victims being clubbed on the hand, hung from meat hooks, and gone after with the chain saw.

We see rooms full of strange altars made from human bones, and rooms filled with chicken feathers and charms and weird relics. And gradually we realize that the house is inhabited by a demented family of retarded murderers and grave robbers. When they get fresh victims, they carve them up with great delight. What they do with the bodies is a little obscure, but, uh, they run a barbecue stand down by the road.

One way or another, all the kids get killed by the maniac waving the chain saw -- except one girl, who undergoes a night of panic and torture, who escapes not once but twice, who leaps through no fewer than two windows, and who screams endlessly. All of this material, as you can imagine, is scary and unpalatable. But the movie is good technically and with its special effects, and we have to give it grudging admiration on that level, despite all the waving of the chain saw.

There is, for example, an effective montage of quick cuts of the last girl’s screaming face and popping eyeballs. There are bizarrely effective performances by the demented family (one of them, of course, turns out to be the hitchhiker, and Grandfather looks like Dustin Hoffman in “Little Big Man”). What we’re left with, though, is an effective production in the service of an unnecessary movie.

Horror and exploitation films almost always turn a profit if they’re brought in at the right price. So they provide a good starting place for ambitious would-be filmmakers who can’t get more conventional projects off the ground. “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre” belongs in a select company (with “Night of the Living Dead” and “Last House on the Left”) of films that are really a lot better than the genre requires. Not, however, that you’d necessarily enjoy seeing it.

His Rating :

suggested by thenoah

johanlefourbe's rating:

The Jerk (1979)

His Review :

Reviewing a comedy can be a tricky business, because the question of whether the comedy was "good" or "bad" depends almost entirely upon whether or not the reviewer was amused. Laughter is quite often an involuntary reaction: If I laugh at something and you don't, no amount of my logic is going to convince you that it was funny.

And so when I say that “The Jerk,” the first major film starring Steve Martin, was not an amusing comedy, I should probably also report that a lot of the people who went to the sneak preview laughed all the way through it. (Others booed—but there you are.)

I can report, however, why I didn't find “The Jerk” very funny. It began to grind on me right at the beginning because it was depending on whats rather than whys for its laughs. I'll explain. It seems to me that there are two basic approaches to any kind of comedy, and in a burst of oversimplification I'll call them the Funny Hat and the Funny Logic approaches. The difference is elementary: In the first, we're supposed to laugh because the comic is wearing the funny hat, and in the second it's funny because of his reasons for wearing the funny hat.

You may have guessed by now that I prefer the Funny Logic approach, and that “The Jerk” is almost entirely a movie of Funny Hats. An example, from the film's opening premise: Steve Martin has been raised as a member of a family of poor black Southern sharecroppers, and, although he is white, it has never occurred to him that he might be adopted. His life is happy until the day he learns the truth, and is sent out into the world to earn his way. He hits the road wearing a World War II bomber's helmet and goggles.

OK. “The Jerk” wants us to laugh at this material just at the most basic level. Martin is white and thinks the blacks are his parents, ha, ha. He wears a funny hat when he hits the road, ho, ho. Those are the whats. What about the whys? Why is he wearing the goggles? So we will laugh. There's no plot point to be made, and nothing is being said about his character—except, of course, that he's a jerk.

By way of comparison, Mel Brooks' "The Producers" (1968) opens in the office of theatrical producer Zero Mostel, who is deeply involved in the inflamed sexual fantasies of a little old lady he hopes will invest in one of his plays. The old lady wants to pretend she's a helpless little milkmaid, and that Mostel is a brawny stable lad who is about to ravish her. They both look absurd while they're playing their roles, of course, and that's the what. But the why—the reasons why Mostel feels he must behave in this ridiculous way, and keep a straight face while he's doing it makes the scene hilarious. The twisted logic beneath the surface—the cockamamie human motives we can identify with—make it comedy instead of a gag.

“The Jerk” is all gags and very little comedy. After Martin hits the road, he has a series of adventures as a gas pump jockey, a weight-guesser in a sideshow, a hapless lover of Bernadette Peters, an inventor of a gadget to keep your eyeglasses from falling down. All of these gag situations are milked for one-time laughs. They don't grow out of his character, or contribute to it.

We laugh at the eyeglass invention because it looks funny when people wear it; it's symbolically a Funny Hat, ho, ho. But nothing is done with it on a character level. And “The Jerk” eventually becomes aggressive and almost hostile in the way it lobs one Funny Hat after another at us: We get the sense at times that the cast and crew arrived at a location, found the script bankrupt of real laughs, and started looking around for funny props.

There's another sense in which “The Jerk” made me uncomfortable. There's a smarmy undercurrent in this movie that seems to imply that Steve Martin may be playing a jerk, but that we all know what a cool guy he is. Well, if you're going to play a jerk, play one as if you think you are one, or you might wind up looking like a jerk.

His Rating :

suggested by thenoah

johanlefourbe's rating:

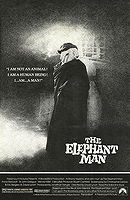

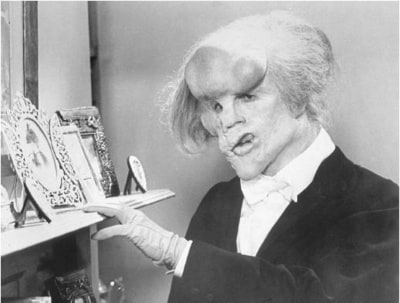

The Elephant Man (1980)

His Review :

The film of The Elephant Man is not based on the successful stage play of the same name, but they both draw their sources from the life of John Merrick, the original "elephant man," whose rare disease imprisoned him in a cruelly misformed body. Both the play and the movie adopt essentially the same point of view, that we are to honor Merrick because of the courage with which he faced his existence.

The Elephant Man forces me to question this position on two grounds: first, on the meaning of Merrick's life, and second, on the ways in which the film employs it. It is conventional to say that Merrick, so hideously misformed that he was exhibited as a sideshow attraction, was courageous. No doubt he was. But there is a distinction here that needs to be drawn, between the courage of a man who chooses to face hardship for a good purpose, and the courage of a man who is simply doing the best he can, under the circumstances.

Wilfrid Sheed, an American novelist who is crippled by polio, once discussed this distinction in a Newsweek essay. He is sick and tired, he wrote, of being praised for his "courage," when he did not choose to contract polio and has little choice but to deal with his handicaps as well as he can. True courage, he suggests, requires a degree of choice. Yet the whole structure of The Elephant Man is based on a life that is said tobe courageous, not because of the hero's achievements, but simply because of the bad trick played on him by fate. In the film and the play (which are similar in many details), John Merrick learns to move in society, to have ladies in to tea, to attend the theater, and to build a scale model of a cathedral. Merrick may have had greater achievements in real life, but the film glosses them over. How, for example, did he learn to speak so well and eloquently? History tells us that the real Merrick's jaw was so misshapen that an operation was necessary just to allow him to talk. In the film, however, after a few snuffles to warm up, he quotes the Twenty-Third Psalm and Romeo and Juliet. This is pure sentimentalism.

The film could have chosen to develop the relationship between Merrick and his medical sponsor, Dr. Frederick Treves, along the lines of the bond between doctor and child in Truffaut's The Wild Child. It could have bluntly dealt with the degree of Merrick's inability to relate to ordinary society, as in Werner Herzog's Kaspar Hauser. Instead, it makes him noble and celebrates his nobility.

I kept asking myself what the film was really trying to say about the human condition as reflected by John Merrick, and I kept drawing blanks. The film's philosophy is this shallow: (1)Wow, the Elephant Man sure looked hideous, and (2)gosh, isn't it wonderful how he kept on in spite of everything? This last is in spite of a real possibility that John Merrick's death at twenty-seven might have been suicide.

The film's technical credits are adequate. John Hurt is very good as Merrick, somehow projecting a humanity past the disfiguring makeup, and Anthony Hopkins is correctly aloof and yet venal as the doctor. The direction, by David (Eraserhead) Lynch, is com-petent, although he gives us an inexcusable opening scene in which Merrick's mother is trampled or scared by elephants or raped_who knows?_and an equally idiotic closing scene in which Merrick becomes the Star Child from 2001, or something.

His Rating :

suggested by thenoah

johanlefourbe's rating:

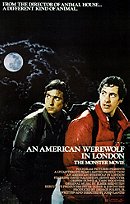

His Review :

"An American Werewolf in London" seems curiously unfinished, as if director John Landis spent all his energy on spectacular set pieces and then didn't want to bother with things like transitions, character development, or an ending. The movie has sequences that are spellbinding, and then long stretches when nobody seems sure what's going on. There are times when the special effects almost wipe the characters off the screen. It's weird. It's not a very good film, and it falls well below Landis's work in the anarchic "National Lampoon's Animal House" and the rambunctious "The Blues Brothers." Landis never seems very sure whether he's making a comedy or a horror film, so he winds up with genuinely funny moments acting as counterpoint to the gruesome undead. Combining horror and comedy is an old tradition (my favorite example is "Bride of Franenstein"), but the laughs and the blood coexist very uneasily in this film.

One of the offscreen stars of the film is Rick Baker, the young makeup genius who created the movie's wounds, gore, and werewolves. His work is impressive, yes, but unless you're single-mindedly interested in special effects, "American Werewolf"is a disappointment. And even the special effects, good as they are, come as an anticlimax if you're a really dedicated horror fan, because if you are, you've already seen this movie's high point before: the onscreen transformation of a man into a werewolf was anticipated in "The Howling," in which the special effects were done by a Baker protege named Rob Bottin.

The movie's plot involves two young American students (David Naughton and Griffin Dunne), who are backpacking across the English moors. They stumble into a country pub where everyone is ominously silent, and then one guy warns them to beware the full moon and stick to the road. They don't, and are attacked by werewolves. Dunne is killed, Naughton is severely wounded, and a few days later in the hospital Naughton is visited by the decaying cadaver of Dunne -- who warns him that he'll turn into a werewolf at the full moon. Naughton ignores the warning, falls in love with his nurse (Jenny Agutter), and moves in with her when he's discharged from the hospital. Then follows a series of increasingly gruesome walk-ons by Dunne, who begs Naughton to kill himself before the full moon. Naughton doesn't, turns into a werewolf, and runs amok through London. That gives director Landis his chance to stage a spectacular multi-car traffic accident in Piccadilly Circus; crashes have been his specialty since the homecoming parade in "Animal House" and the nonstop carnage in "The Blues Brothers."

The best moments in "American Werewolf" probably belong to Dunne, who may be a decaying cadaver but keeps right on talking like a college student: "Believe me," he says at Naughton's bedside, "this isn't a whole lot of fun." The scene in which Naughton turns into a werewolf is well done, with his hands elongating and growing claws, and his face twisting into a snout and fangs. But it's as if John Landis thought the technology would be enough. We never get a real feeling for the characters, we never really believe the places (especially that awkwardly phony pub and its stagy customers), and we are particularly disappointed by the ending. I won't reveal the ending, such as it is, except to say it's so sudden, arbitrary, and anticlimactic that, although we are willing for the movie to be over, we still can't quite believe it.

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982)

His Review :

How could they do this to Jennifer Jason Leigh? How could they put such a fresh and cheerful person into such a scuz-pit of a movie? Don't they know they have a star on their hands? I didn't even know who Leigh was when I walked into "Fast Times at Ridgemont High," and yet I was completely won over by her. She contained so much life and light that she was a joy to behold. And then she and everybody else in this so-called comedy is invited to plunge into offensive vulgarity.

Let me make myself clear. I am not against vulgarity as a subject for a movie comedy. Sometimes I treasure it, when it's used with inspiration, as in "The Producers" or "National Lampoon's Animal House." But vulgarity is a very tricky thing to handle in a comedy; tone is everything, and the makers of "Fast Times at Ridgemont High" have an absolute gift for taking potentially funny situations and turning them into general embarrassment. They're tone-deaf.

The movie's another one of those adolescent sex romps, such as "Porky's" and "Animal House," in which part of the humor comes from raunchy situations and dialogue. This movie is so raunchy, however, that the audience can't quite believe it. I went to a sneak preview thrown by a rock radio station, and the audience had come for a good time. But during a scene involving some extremely frank talk about certain popular methods of sexual behavior, even the rock fans were grossed out. There's a difference between raunchiness and gynecological detail.

The movie's cast struggles valiantly through all this dreck. Rarely have I seen so many attractive young performers invited to appear in so many unattractive scenes. Leigh, for example, plays a virginal young student at Ridgemont High. She's curious about sex, so the script immediately turns her into a promiscuous sex machine who will go to bed with anybody. And then her sexual experiences all turn out to have an unnecessary element of realism, so that we have to see her humiliated, disappointed, and embarrassed. Whatever happened to upbeat sex? Whatever happened to love and lust and romance, and scenes where good-looking kids had a little joy and excitement in life, instead of all this grungy downbeat humiliation? Why does someone as pretty as Leigh have to have her nudity exploited in shots where the only point is to show her ill-at-ease?

If this movie had been directed by a man, I'd call it sexist. It was directed by a woman, Amy Heckerling -- and it's sexist all the same. It clunks to a halt now and then for some heartfelt, badly handled material about pregnancy and abortion. I suppose that's Heckerling paying dues to some misconception of the women's movement. But for the most part this movie just exploits its performers by trying to walk a tightrope between comedy and sexploitation.

In addition to Leigh's work, however, there are some other good performances. Sean Penn is perfect as the pot-smoking space cadet who has been stoned since the third grade. Phoebe Cates is breathtaking as the more experienced girl who gives Leigh those distasteful lessons in love. Judge Reinhold has fun as a perennial fast-food cook who rebels against the silly uniforms he's supposed to wear. Ray Walston is suitably hateful as the dictatorial history teacher, Mr. Hand. But this movie could have been a lot more fun if it hadn't chosen to confuse embarrassment with humor. The unnecessary detail about sexual functions isn't funny, it's distasteful.

Leigh looks so young, fresh, cheerful, and innocent that we don't laugh when she gets into unhappy scenes with men -- we wince. The whole movie is a failure of taste, tone, and nerve -- the waste of a good cast on erratic, offensive material that hasn't been thought through, or maybe even thought about.

His Rating :

suggested by Goofoff

johanlefourbe's rating:

The Thing (1982)

His Review :

A spaceship crash-lands on Earth countless years ago and is buried under Antarctic ice. It has a creature on board. Modern scientists dig up the creature, thaw it out, and discover too late that it still lives--and has the power to imitate all life-forms. Its desire to live and expand is insatiable. It begins to assume the identities of the scientists at an isolated Antarctic research station. The crucial question becomes: Who is real, and who is the Thing? The original story was called "Who Goes There?" It was written by John W. Campbell, Jr., in the late 1930s, and it provided such a strong and scary story that it inspired at least four movie versions before this one: The original "The Thing from Another World" in 1951, "Invasion of the Body Snatchers" in 1956 and 1978, "Alien" in 1979, and now John Carpenter's 1982 remake, again called "The Thing."

I mention the previous incarnations of "The Thing" not to demonstrate my mastery of The Filmgoer's Companion, but to suggest the many possible approaches to this material. The two 1950s versions, especially "Invasion of the Body Snatchers," were seen at the time as fables based on McCarthyism; communists, like victims of the Thing, looked, sounded, and acted like your best friend, but they were infected with a deadly secret. "Alien," set on a spaceship but using the same premise, paid less attention to the "Who Goes There?" idea and more to the special effects: Remember that wicked little creature that tore its way out of the astronaut's stomach? Now comes this elaborate version by John Carpenter, a master of suspense ("Halloween"). His "Thing" depends on its special effects, which are among the most elaborate, nauseating, and horrifying sights yet achieved by Hollywood's new generation of visual magicians. There are times when we seem to be sticking our heads right down into the bloody, stinking maw of the unknown, as the Thing transforms itself into creatures with the body parts of dogs, men, lobsters, and spiders, all wrapped up in gooey intestines.

"The Thing" is a great barf-bag movie, all right, but is it any good? I found it disappointing, for two reasons: the superficial characterizations and the implausible behavior of the scientists on that icy outpost. Characters have never been Carpenter's strong point; he says he likes his movies to create emotions in his audiences, and I guess he'd rather see us jump six inches than get involved in the personalities of his characters. This time, though, despite some roughed-out typecasting and a few reliable stereotypes (the drunk, the psycho, the hero), he has populated his ice station with people whose primary purpose in life is to get jumped on from behind. The few scenes that develop characterizations are overwhelmed by the scenes in which the men are just setups for an attack by the Thing.

That leads us to the second problem, plausibility. We know that the Thing likes to wait until a character is alone, and then pounce, digest, and imitate him--by the time you see Doc again, is he still Doc, or is he the Thing? Well, the obvious defense against this problem is a watertight buddy system, but, time and time again, Carpenter allows his characters to wander off alone and come back with silly grins on their faces, until we've lost count of who may have been infected, and who hasn't. That takes the fun away.

"The Thing" is basically, then, just a geek show, a gross-out movie in which teenagers can dare one another to watch the screen. There's nothing wrong with that; I like being scared and I was scared by many scenes in THE THING. But it seems clear that Carpenter made his choice early on to concentrate on the special effects and the technology and to allow the story and people to become secondary. Because this material has been done before, and better, especially in the original "The Thing" and in "Alien," there's no need to see this version unless you are interested in what the Thing might look like while starting from anonymous greasy organs extruding giant crab legs and transmuting itself into a dog. Amazingly, I'll bet that thousands, if not millions, of moviegoers are interested in seeing just that.

His Rating :

suggested by AVPGuyver21

johanlefourbe's rating:

Day of the Dead (1985)

His Review :

The zombies in "Day of the Dead" are marvels of special effects, with festoons of rotting flesh hanging from their purple limbs as they slouch toward the camera, moaning their sad songs. Truth to tell, they look a lot better than the zombies in "Night of the Living Dead," which was director George Romero's original zombi film. His technology is improving; perhaps the current emphasis on well-developed bodies (in "Perfect," "Rambo," etc.) has inspired a parallel improvement in dead bodies.

But the zombies have another problem in "Day of the Dead": They're upstaged by the characters who are supposed to be real human beings. You might assume that it would be impossible to steal a scene from a zombi, especially one with blood dripping from his orifices, but you haven't seen the overacting in this movie. The characters shout their lines from beginning to end, their temples pound with anger, and they use distracting Jamaican and Irish accents, until we are so busy listening to their endless dialogue that we lose interest in the movie they occupy.

Maybe there's a reason for that. Maybe Romero, whose original movie was a genuine inspiration, hasn't figured out anything new to do with his zombies. In his second zombi film, the brilliant "Dawn of the Dead" (1980), he had them shuffling and moaning their way through a modern shopping mall, as Muzak droned in the background and terrified survivors took refuge in the Sears store. The effect was both frightening and satirical. The everyday location made the zombies seem all the more horrible, and the shopping mall provided lots of comic props (as when several zombies tried to crawl up the down escalator).

This time, though, Romero has centered the action in a visually dreary location - an underground storage cavern, one of those abandoned salt mines where they store financial records and the master prints of old movies. The zombies have more or less overrun the surface of America, we gather, and down in the darkness a small team of scientists and military men are conducting experiments on a few captive zombi guinea-pigs.

It's an intriguing idea, especially if Romero had kept the semiseriousness of the earlier films. Instead, the chief researcher is a demented butcher with blood-stained clothes, whose idea of science is to teach a zombi named Bub to operate a Sony Walkman. Meanwhile, the head of the military contingent (Joseph Pilato) turns into a violent little dictator who establishes martial law and threatens to end the experiments. His opponent is a spunky woman scientist (Lori Cardille), and as they shout angry accusations at each other, the real drama in the film gets lost.

In the earlier films, we really identified with the small cadre of surviving humans. They were seen as positive characters, and we cared about them. This time, the humans are mostly unpleasant, violent, insane or so noble that we can predict with utter certainty that they will survive. According to the mad scientist in "Day of the Dead," the zombies keep moving because of primitive impulses buried deep within their spinal columns - impulses that create the appearance of life long after consciousness and intelligence have departed. I hope the same fate doesn't befall Romero's zombi movies. He should quit while he's ahead.

His Rating :

suggested by AVPGuyver21

johanlefourbe's rating:

Brazil (1985)

His Review :

Just as George Orwell's 1984 is an alternate vision of the past, present and future, so "Brazil" is a variation of Orwell's novel. The movie happens in a time and place that seem vaguely like our own, but with different graphics, hardware and politics. Society is controlled by a monolithic organization, and citizens lead a life of paranoia and control. Thought police are likely to come crashing through the ceiling and start bashing dissenters. Life is mean and grim.

The hero of "Brazil" is Sam Lowry (Jonathan Pryce), a meek, desperate little man who works at a computer terminal all day.

Occasionally he cheats; when the boss isn't looking, he and his fellow workers switch the screens of their computers to reruns of exciting old TV programs. Sam knows his life is drab and lockstep, but he sees no way out of it. His only escape is into his fantasies - into glorious dreams of flying high above all the petty cares of the world, urged on by the vision of a beautiful woman.

His everyday life offers no such possibilities. Even the basic mechanisms of life support seem to be failing, and one scene early in the movie has Robert De Niro in a walk-on as an illegal free-lance repairman who defies the state by fixing things. De Niro makes his escape by sliding down long cables to freedom, like Spider-Man. For Sam, there seems to be no escape.

But then he gets involved in an intrigue that involves the girl of his dreams, the chief executive of the state and a shadowy band of dissenters. All of this is strangely familiar; the outlines of "Brazil" are much the same as those of 1984, but the approach is different.

While Orwell's lean prose was translated last year into an equally lean and dour film, "Brazil" seems almost like a throwback to the psychedelic 1960s, to an anarchic vision in which the best way to improve things is to blow them up.

The other difference between the two worlds - Orwell's and the one created here by director and co-writer Terry Gilliam - is that Gilliam apparently has had no financial restraints. Although "Brazil" has had a checkered history since it was made (for a long time, Universal Pictures seemed unwilling to release it), there was a lot of money available to make it. The movie is awash in elaborate special effects, sensational sets, apocalyptic scenes of destruction and a general lack of discipline. It's as if Gilliam sat down and wrote out all of his fantasies, heedless of production difficulties, and then they were filmed - this time, heedless of sense.

The movie is very hard to follow. I have seen it twice, and am still not sure exactly who all the characters are, or how they fit.

Perhaps it is not supposed to be clear; perhaps the movie's air of confusion is part of its paranoid vision. There are individual moments that create sharp images (shock troops drilling through a ceiling, De Niro wrestling with the almost obscene wiring and tubing inside a wall, the movie's obsession with bizarre duct work), but there seems to be no sure hand at the controls.

The best scene in the movie is one of the simplest, as Sam moves into half an office and finds himself engaged in a tug-of-war over his desk with the man through the wall. I was reminded of a Chaplin film, "Modern Times," and reminded, too, that in Chaplin economy and simplicity were virtues, not the enemy.

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

Blue Velvet (1986)

His Review :

"Blue Velvet" contains scenes of such raw emotional energy that it's easy to understand why some critics have hailed it as a masterpiece. A film this painful and wounding has to be given special consideration.

And yet those very scenes of stark sexual despair are the tipoff to what's wrong with the movie. They're so strong that they deserve to be in a movie that is sincere, honest and true. But "Blue Velvet" surrounds them with a story that's marred by sophomoric satire and cheap shots. The director is either denying the strength of his material or trying to defuse it by pretending it's all part of a campy in-joke.

The movie has two levels of reality. On one level, we're in Lumberton, a simple-minded small town where people talk in television cliches and seem to be clones of 1950s sitcom characters. On another level, we're told a story of sexual bondage, of how Isabella Rossellini's husband and son have been kidnapped by Dennis Hopper, who makes her his sexual slave. The twist is that the kidnapping taps into the woman's deepest feelings: She finds that she is a masochist who responds with great sexual passion to this situation.

Everyday town life is depicted with a deadpan irony; characters use lines with corny double meanings and solemnly recite platitudes.

Meanwhile, the darker story of sexual bondage is told absolutely on the level in cold-blooded realism.

The movie begins with a much praised sequence in which picket fences and flower beds establish a small-town idyll. Then a man collapses while watering the lawn, and a dog comes to drink from the hose that is still held in his unconscious grip. The great imagery continues as the camera burrows into the green lawn and finds hungry insects beneath - a metaphor for the surface and buried lives of the town.

The man's son, a college student (Kyle MacLachlan), comes home to visit his dad's bedside and resumes a romance with the daughter (Laura Dern) of the local police detective. MacLachlan finds a severed human ear in a field, and he and Dern get involved in trying to solve the mystery of the ear. The trail leads to a nightclub singer (Rossellini) who lives alone in a starkly furnished flat.

In a sequence that Hitchcock would have been proud of, MacLachlan hides himself in Rossellini's closet and watches, shocked, as she has a sadomashochistic sexual encounter with Hopper, a drug-sniffing pervert.

Hopper leaves. Rossellini discovers MacLachlan in the closet and, to his astonishment, pulls a knife on him and forces him to submit to her seduction. He is appalled but fascinated; she wants him to be a "bad boy" and hit her.

These sequences have great power. They make "9 1/2 Weeks" look rather timid by comparison, because they do seem genuinely born from the darkest and most despairing side of human nature. If "Blue Velvet" had continued to develop its story in a straight line, if it had followed more deeply into the implications of the first shocking encounter between Rossellini and MacLachlan, it might have made some real emotional discoveries.

Instead, director David Lynch chose to interrupt the almost hypnotic pull of that relationship in order to pull back to his jokey, small-town satire. Is he afraid that movie audiences might not be ready for stark S & M unless they're assured it's all really a joke? I was absorbed and convinced by the relationship between Rossellini and MacLachlan, and annoyed because the director kept placing himself between me and the material. After five or 10 minutes in which the screen reality was overwhelming, I didn't need the director prancing on with a top hat and cane, whistling that it was all in fun.

Indeed, the movie is pulled so violently in opposite directions that it pulls itself apart. If the sexual scenes are real, then why do we need the sendup of the "Donna Reed Show"? What are we being told? That beneath the surface of Small Town, U.S.A., passions run dark and dangerous? Don't stop the presses.

The sexual material in "Blue Velvet" is so disturbing, and the performance by Rosellini is so convincing and courageous, that it demands a movie that deserves it. American movies have been using satire for years to take the edge off sex and violence. Occasionally, perhaps sex and violence should be treated with the seriousness they deserve. Given the power of the darker scenes in this movie, we're all the more frustrated that the director is unwilling to follow through to the consequences of his insights.

"Blue Velvet" is like the guy who drives you nuts by hinting at horrifying news and then saying, "Never mind." There's another thing. Rossellini is asked to do things in this film that require real nerve. In one scene, she's publicly embarrassed by being dumped naked on the lawn of the police detective. In others, she is asked to portray emotions that I imagine most actresses would rather not touch. She is degraded, slapped around, humiliated and undressed in front of the camera. And when you ask an actress to endure those experiences, you should keep your side of the bargain by putting her in an important film.

That's what Bernardo Bertolucci delivered when he put Marlon Brando and Maria Schneider through the ordeal of "Last Tango in Paris." In "Blue Velvet," Rossellini goes the whole distance, but Lynch distances himself from her ordeal with his clever asides and witty little in-jokes. In a way, his behavior is more sadistic than the Hopper character.

What's worse? Slapping somebody around, or standing back and finding the whole thing funny?

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

Top Gun (1986)

His Review :

In the opening moments of "Top Gun," an ace Navy pilot flies upside down about 18 inches above a Russian-built MiG and snaps a Polaroid picture of the enemy pilot. Then he flips him the finger and peels off.

It's a hot-dog stunt, but it makes the pilot (Tom Cruise) famous within the small circle of Navy personnel who are cleared to receive information about close encounters with enemy aircraft. And the pilot, whose code name is Maverick, is selected for the Navy's elite flying school, which is dedicated to the dying art of aerial dogfights.

The best graduate from each class at the school is known as "Top Gun." And there, I think, you have the basic materials of this movie, except, of course, for three more obligatory ingredients in all movies about brave young pilots: (1) the girl, (2) the mystery of the heroic father and (3) the rivalry with another pilot. It turns out that Maverick's dad was a brilliant Navy jet pilot during the Vietnam era, until he and his plane disappeared in unexplained circumstances. And it also turns out that one of the instructors at the flying school is a pretty young brunet (Kelly McGillis) who wants to know a lot more about how Maverick snapped that other pilot's picture.

"Top Gun" settles fairly quickly into alternating ground and air scenes, and the simplest way to sum up the movie is to declare the air scenes brilliant and the earthbound scenes grimly predictable. This is a movie that comes in two parts: It knows exactly what to do with special effects, but doesn't have a clue as to how two people in love might act and talk and think.

Aerial scenes always present a special challenge in a movie.

There's the danger that the audience will become spatially disoriented.

We're used to seeing things within a frame that respects left and right, up and down, but the fighter pilot lives in a world of 360-degree turns. The remarkable achievement in "Top Gun" is that it presents seven or eight aerial encounters that are so well choreographed that we can actually follow them most of the time, and the movie gives us a good secondhand sense of what it might be like to be in a dogfight.

The movie's first and last sequences involve encounters with enemy planes. Although the planes are MiGs, the movie provides no nationalities for their pilots. We're told the battles take place in the Indian Ocean, and that's it. All of the sequences in between take place at Top Gun school, where Maverick quickly gets locked into a personal duel with another brillant pilot, Iceman (Val Kilmer). In one sequence after another, the sound track trembles as the sleek planes pursue each other through the clouds, and, yeah, it's exciting. But the love story between Cruise and McGillis is a washout.

It's pale and unconvincing compared with the chemistry between Cruise and Rebecca De Mornay in "Risky Business," and between McGillis and Harrison Ford in "Witness" - not to mention between Richard Gere and Debra Winger in "An Officer and a Gentleman," which obviously inspired "Top Gun." Cruise and McGillis spend a lot of time squinting uneasily at each other and exchanging words as if they were weapons, and when they finally get physical, they look like the stars of one of those sexy new perfume ads. There's no flesh and blood here, which is remarkable, given the almost palpable physical presence McGillis had in "Witness." In its other scenes on the ground, the movie seems content to recycle old cliches and conventions out of countless other war movies.

Wouldn't you know, for example, that Maverick's commanding officer at the flying school is the only man who knows what happened to the kid's father in Vietnam? And are we surprised when Maverick's best friend dies in his arms? Is there any suspense as Maverick undergoes his obligatory crisis of conscience, wondering whether he can ever fly again? Movies like "Top Gun" are hard to review because the good parts are so good and the bad parts are so relentless. The dogfights are absolutely the best since Clint Eastwood's electrifying aerial scenes in "Firefox." But look out for the scenes where the people talk to one another.

His Rating :

suggested by filmbuilder

johanlefourbe's rating:

Spaceballs (1987)

His Review :

Did Mel Brooks make "Spaceballs" to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the "Star Wars" saga? Last month we celebrated the first decade of George Lucas's great entertainment, and now here is Brooks's satire, complete with Dark Helmet and Pizza the Hutt.

I enjoyed a lot of the movie, but I kept thinking I was at a revival. The strangest thing about "Spaceballs" is that it should have been made several years ago, before our appetite for "Star Wars" satires had been completely exhausted.

Brooks's first features, "The Producers" (1968) and "The Twelve Chairs," told original stories. Since then, he has specialized in movie satires; his targets include Frankenstein, Hitchcock, Westerns, silent movies and historical epics. I usually find a few very big laughs and a lot of smaller ones in his movies, but the earlier ones are stronger than the more recent films, and I keep wishing Brooks would satirize something current and tricky, like the John Hughes teenage films, instead of picking on old targets. With "Spaceballs," he has made the kind of movie that didn't really need a Mel Brooks. In bits and pieces, one way or another, this movie already has been made over the last 10 years by countless other satirists.

After a fabulous and increasingly funny opening shot of one of those massive George Lucas space cruisers, he launches into a cheerfully silly story about the planet Spaceball and its attempt to steal the atmosphere of its peaceful neighbor, Druidia.

The heroes and villains are all clones of "Star Wars" regulars. Bill Pullman is Lone Starr, free-lance space jockey. John Candy is Barf, a "mog" (half man, half dog). Rick Moranis is Dark Helmet, always complaining about something. Daphne Zuniga plays Princes Vespa, and so on. Brooks himself gives two of the movie's best performances: as Skroob, the president of Spaceball, and as Yogurt, the wise old man who keeps saying "May the Schwartz be with you" as if he's sure it will eventually get a laugh.

The movie's dialogue is constructed out of funny names, puns and old jokes. Sometimes it's painfully juvenile. But there are some great visual gags in the movie, and the best is Pizza the Hutt, a creature who roars and cajoles while cheese melts off its forehead and big hunks of pepperoni slide down its jowls.

I dunno. How do you review a movie like this, anyway? I guess by saying whether you laughed or not. I did laugh, but not enough to recommend the film. I keep waiting for Mel Brooks to do something really great, instead of these machine-made satires, where three-quarters of the invention goes into the special-effects technology.

As a producer of other people's movies, Brooks has an amazing track record; his company made "The Elephant Man," "My Favorite Year," "Frances" and "The Fly." But Brooks's intelligence and taste seem to switch off when he makes his own films, and he aims for broad, dumb comedy: Jokes about names with dirty double meanings are his big specialty. Maybe the reason "Spaceballs" isn't better is that he was deliberately aiming low, going for the no-brainer satire. What does he really think about "Star Wars," or anything else, for that matter?

Brooks got his start as a writer for Sid Caesar, and sometimes he still seems to be writing for early 1950s television. He is smarter than his films, and sometimes that translates into a feeling that he underestimates his audiences. He is potentially a great comedy director. In 1987, he shouldn't be making "Star Wars" satires. May the Schwartz help him to realize his potential, already.

His Rating :

johanlefourbe's rating:

Full Metal Jacket (1987)

His Review :