Nouveau Roman/New Novel Movement

Nouveau Roman is a literary movement in France during the 1950s. It gathered French novelists who diverged from classical literary genres, experimenting with style instead of following the standard rules of the novel that focused on plot, idea, action, and narrative. The writers focused on ideas, making the nouveau roman work as an individual vision of things. Readers are challenged more, as the fiction is written in a condensed, repetitive manner with no intention of explaining characters and their actions. The authors simply explored a variety of problems that individuals were faced with in the contemporary world, such as individual and collective identities, responsibilities, loyalties, and the alienation of life in a technological and consumerist society. Nothing is definite; it is up to the reader to reach a conclusion as to what happened and why.

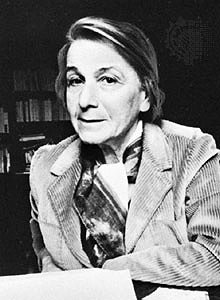

The group consisted of individuals without anything in common except for the resistance to classical literary expression. Their common trait was that they took literature seriously, and that they were respected as avant-garde writers and prominent intellectuals who were attached to the literary theory as well as to the practice of it. This made the group a major literary movement in France at least for a decade. The first novel of the "Nouveau Rroman" is considered to be "Tropismes" (1938), written by a French novelist and literary critic Nathalie Sarraute.

They, themselves, never felt any belonging to a certain group or movement. It was the media that made their collective existence; they were promoted by "L' Express" magazine and by the" Minuit" publishing house, and popularized by the literary theorist Jean Ricardou through an avant-garde critical journal "Tel Quel." Influenced by film art, the group contributed to a new style of filmmaking, named the "New Wave."

Source:

writershistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=category§ionid=4&id=27&Itemid=40

Further readings:

theculturetrip.com/europe/france/articles/alain-robbe-grillet-and-the-nouveau-roman-movement/

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_roman

fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_roman

www.enotes.com/topics/french-new-novel

The group consisted of individuals without anything in common except for the resistance to classical literary expression. Their common trait was that they took literature seriously, and that they were respected as avant-garde writers and prominent intellectuals who were attached to the literary theory as well as to the practice of it. This made the group a major literary movement in France at least for a decade. The first novel of the "Nouveau Rroman" is considered to be "Tropismes" (1938), written by a French novelist and literary critic Nathalie Sarraute.

They, themselves, never felt any belonging to a certain group or movement. It was the media that made their collective existence; they were promoted by "L' Express" magazine and by the" Minuit" publishing house, and popularized by the literary theorist Jean Ricardou through an avant-garde critical journal "Tel Quel." Influenced by film art, the group contributed to a new style of filmmaking, named the "New Wave."

Source:

writershistory.com/index.php?option=com_content&task=category§ionid=4&id=27&Itemid=40

Further readings:

theculturetrip.com/europe/france/articles/alain-robbe-grillet-and-the-nouveau-roman-movement/

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_roman

fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nouveau_roman

www.enotes.com/topics/french-new-novel

Sort by:

Showing 17 items

Rating:

List Type:

Sarraute dedicated herself to literature, with her most prominent work being Portrait of a Man Unknown (1948), a work applauded by Jean-Paul Sartre, who famously referred to it as an "anti-novel" and who also contributed a foreword. Despite such high critical praise, however, the work only drew notice from literary insiders, as did her follow-up, Martereau.

Sarraute's essay The Age of Suspicion (L'Ère du soupçon, 1956) served as a prime manifesto for the nouveau roman literary movement, alongside Alain Robbe-Grillet's For a New Novel. Sarraute became, along with Robbe-Grillet, Claude Simon, Marguerite Duras, and Michel Butor, one of the figures most associated with the rise of this new trend in writing, which sought to radically transform traditional narrative models of character and plot. (Wikipedia)

Sarraute's essay The Age of Suspicion (L'Ère du soupçon, 1956) served as a prime manifesto for the nouveau roman literary movement, alongside Alain Robbe-Grillet's For a New Novel. Sarraute became, along with Robbe-Grillet, Claude Simon, Marguerite Duras, and Michel Butor, one of the figures most associated with the rise of this new trend in writing, which sought to radically transform traditional narrative models of character and plot. (Wikipedia)

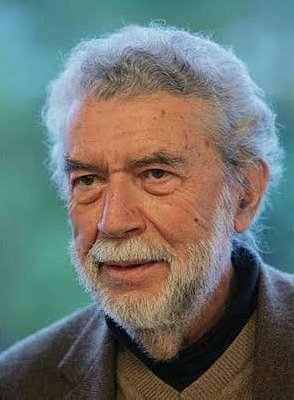

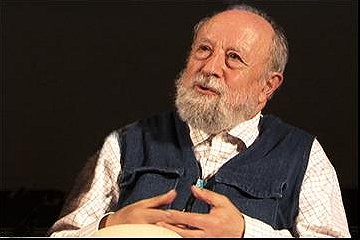

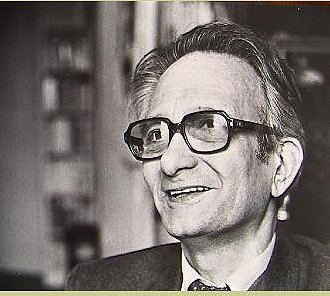

Robbe-Grillet's first published novel was The Erasers (Les Gommes), which was issued by Les Éditions de Minuit in 1953. After that, he dedicated himself full-time to his new occupation. His early work was praised by eminent critics, such as Roland Barthes and Maurice Blanchot. Around the time of his second novel, he became a literary advisor for Les Éditions de Minuit and occupied this position from 1955 until 1985. After publishing four novels, in 1961, he worked with Alain Resnais, writing the script for Last Year in Marienbad (L'Année dernière à Marienbad), and he subsequently wrote and directed his own films.

In 1963, Robbe-Grillet published For a New Novel (Pour un Nouveau Roman), a collection of previously-published theoretical writings concerning the novel. From 1966 to 1968, he was a member of the High Committee for the Defense and Expansion of French (Haut comité pour la défense et l'expansion de la langue française). In addition, Robbe-Grillet also led the Centre for Sociology of Literature (Centre de sociologie de la littérature) at the Université Libre de Bruxelles from 1980 to 1988. From 1971 to 1995, Robbe-Grillet was a professor at New York University, lecturing on his own novels.

Although Robbe-Grillet was elected to the Académie française in 2004, in his eighties, he never was formally received by the Académie because of disputes regarding the Académie's reception procedures. Robbe-Grillet both refused to prepare and submit a welcome speech in advance, preferring to improvise his speech, as well as refusing to purchase and wear the Académie's famous green tails (habit vert) and sabre, which he considered outdated.

His writing style has been described as "realist" or "phenomenological" (in the Heideggerian sense) or "a theory of pure surface." Methodical, geometric, and often repetitive descriptions of objects replace (though often reveal) the psychology and interiority of the character. The reader must slowly piece together the story and the emotional experience of jealousy, for example, in the repetition of descriptions, the attention to odd details, and the breaks in repetitions, a method that resembles the experience of psychoanalysis in which the deeper unconscious meanings are contained in the flow and disruptions of free associations. Timelines and plots are fractured, and the resulting novel resembles the literary equivalent of a cubist painting. Yet his work is ultimately characterized by its ability to mean many things to many different people.[2] (Wikipedia)

In 1963, Robbe-Grillet published For a New Novel (Pour un Nouveau Roman), a collection of previously-published theoretical writings concerning the novel. From 1966 to 1968, he was a member of the High Committee for the Defense and Expansion of French (Haut comité pour la défense et l'expansion de la langue française). In addition, Robbe-Grillet also led the Centre for Sociology of Literature (Centre de sociologie de la littérature) at the Université Libre de Bruxelles from 1980 to 1988. From 1971 to 1995, Robbe-Grillet was a professor at New York University, lecturing on his own novels.

Although Robbe-Grillet was elected to the Académie française in 2004, in his eighties, he never was formally received by the Académie because of disputes regarding the Académie's reception procedures. Robbe-Grillet both refused to prepare and submit a welcome speech in advance, preferring to improvise his speech, as well as refusing to purchase and wear the Académie's famous green tails (habit vert) and sabre, which he considered outdated.

His writing style has been described as "realist" or "phenomenological" (in the Heideggerian sense) or "a theory of pure surface." Methodical, geometric, and often repetitive descriptions of objects replace (though often reveal) the psychology and interiority of the character. The reader must slowly piece together the story and the emotional experience of jealousy, for example, in the repetition of descriptions, the attention to odd details, and the breaks in repetitions, a method that resembles the experience of psychoanalysis in which the deeper unconscious meanings are contained in the flow and disruptions of free associations. Timelines and plots are fractured, and the resulting novel resembles the literary equivalent of a cubist painting. Yet his work is ultimately characterized by its ability to mean many things to many different people.[2] (Wikipedia)

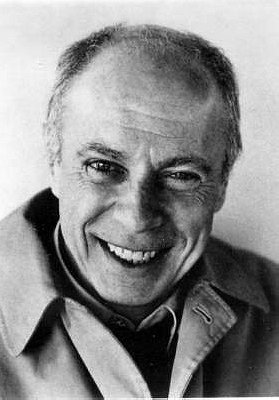

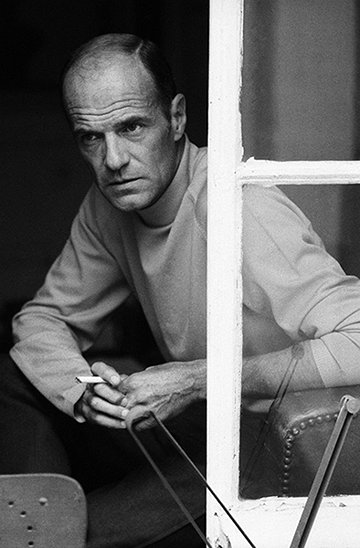

Duras's early novels were fairly conventional in form (their 'romanticism' was criticised by fellow writer Raymond Queneau); however, with Moderato Cantabile she became more experimental, paring down her texts to give ever-increasing importance to what was not said. She was associated with the Nouveau roman French literary movement, although she did not belong definitively to any group. Many of her works, such as Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein (1964) and L'Homme assis dans le couloir (1980) deal with human sexuality.[1] Her films are also experimental in form; most eschew synchronized sound, using voice over to allude to, rather than tell, a story; spoken text is juxtaposed with images whose relation to what is said may be more-or-less indirect. She was noted for her command of dialogue. (Wikipedia)

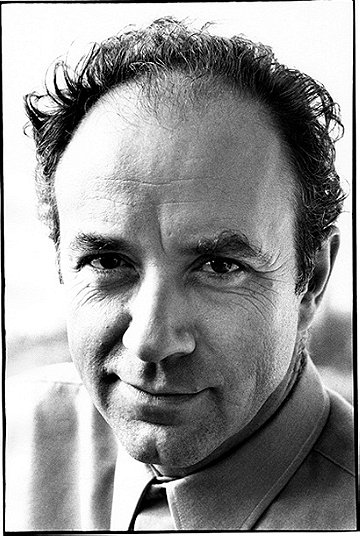

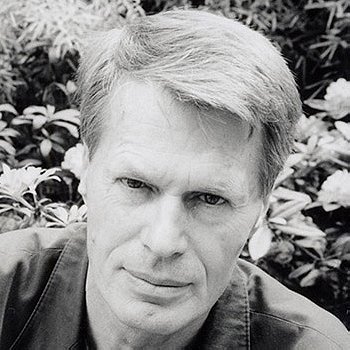

Simon is often identified with the nouveau roman movement exemplified in the works of Alain Robbe-Grillet and Michel Butor, and while his fragmented narratives certainly contain some of the formal disruption characteristic of that movement (in particular Histoire , 1967, Triptyque, 1973), he nevertheless retains a strong sense of narrative and character.[1]

In fact, Simon arguably has much more in common with his Modernist predecessors than with his contemporaries; in particular, the works of Marcel Proust and William Faulkner are a clear influence. Simon's use of self-consciously long sentences (often stretching across many pages and with parentheses sometimes interrupting a clause which is only completed pages later) can be seen to reference Proust's own style, and Simon moreover makes use of certain Proustian settings (in La Route des Flandres, for example, the narrator's captain de Reixach is shot by a sniper concealed behind a hawthorn hedge or haie d'aubépines, a reference to the meeting between Gilberte and the narrator across a hawthorn hedge in Proust's A la recherche du temps perdu).

The Faulknerian influence is evident in the novels' extensive use of a fractured timeline with frequent and potentially disorienting analepsis (moments of chronological discontinuity), and of an extreme form of free indirect speech in which narrative voices (often unidentified) and streams of consciousness bleed into the words of the narrator. The ghost of Faulkner looms particularly large in 1989's L'Acacia, which uses a number of non-sequential calendar dates covering a wide chronological period in lieu of chapter headings, a device borrowed from Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury. (Wikipedia)

In fact, Simon arguably has much more in common with his Modernist predecessors than with his contemporaries; in particular, the works of Marcel Proust and William Faulkner are a clear influence. Simon's use of self-consciously long sentences (often stretching across many pages and with parentheses sometimes interrupting a clause which is only completed pages later) can be seen to reference Proust's own style, and Simon moreover makes use of certain Proustian settings (in La Route des Flandres, for example, the narrator's captain de Reixach is shot by a sniper concealed behind a hawthorn hedge or haie d'aubépines, a reference to the meeting between Gilberte and the narrator across a hawthorn hedge in Proust's A la recherche du temps perdu).

The Faulknerian influence is evident in the novels' extensive use of a fractured timeline with frequent and potentially disorienting analepsis (moments of chronological discontinuity), and of an extreme form of free indirect speech in which narrative voices (often unidentified) and streams of consciousness bleed into the words of the narrator. The ghost of Faulkner looms particularly large in 1989's L'Acacia, which uses a number of non-sequential calendar dates covering a wide chronological period in lieu of chapter headings, a device borrowed from Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury. (Wikipedia)

Journalists and critics have associated his novels with the nouveau roman, but Butor himself has long resisted that association. The main point of similarity is a very general one, not much beyond that; like exponents of the nouveau roman, he can be described as an experimental writer. His best-known novel, La Modification, for instance, is written entirely in the second person.[citation needed] In his 1967 La critique et l'invention, he famously said that even the most literal quotation is already a kind of parody because of its "trans-contextualization."

For decades now, he has chosen to work in other forms, from essays to poetry to artist's books[5] to unclassifiable works like Mobile. Literature, painting and travel are subjects particularly dear to Butor. Part of the fascination of his writing is the way it combines the rigorous symmetries that led Roland Barthes to praise him as an epitome of structuralism (exemplified, for instance, by the architectural scheme of Passage de Milan or the calendrical structure of L'emploi du temps) with a lyrical sensibility more akin to Baudelaire than to Robbe-Grillet. (Wikipedia)

For decades now, he has chosen to work in other forms, from essays to poetry to artist's books[5] to unclassifiable works like Mobile. Literature, painting and travel are subjects particularly dear to Butor. Part of the fascination of his writing is the way it combines the rigorous symmetries that led Roland Barthes to praise him as an epitome of structuralism (exemplified, for instance, by the architectural scheme of Passage de Milan or the calendrical structure of L'emploi du temps) with a lyrical sensibility more akin to Baudelaire than to Robbe-Grillet. (Wikipedia)

Jean Ricardou (b. Cannes, 17 June 1932) is a French writer and theorist of the nouveau roman literary movement.[1] Between 1962 and 1971, Ricardou was on the editorial board of French avant-garde journal Tel Quel. (Wikipedia)

In 1996 his travelogue Eine winterliche Reise zu den Flüssen Donau, Save, Morawa und Drina oder Gerechtigkeit für Serbien (A Journey to the Rivers: Justice for Serbia) created considerable controversy, as Handke portrayed Serbia among the victims of the Yugoslav Wars. In the same essay, Handke also attacked Western media for misrepresenting the causes and consequences of the war. Former Yugoslavian president Slobodan Milošević asked that Handke be summoned as witness for the defence before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, but the writer declined. He did, however, visit the tribunal as a spectator, and later published his observations in Die Tablas von Daimiel (The Tablas of Daimiel). In 1999, Salman Rushdie wrote that Handke "has astonished even his most fervent admirers by his current series of impassioned apologias for the genocidal regime of Slobodan Milosevic." He noted that Handke received the Order of the Serbian Knight from Milosevic for his propaganda services during a visit to Belgrade, and that his "previous idiocies include the suggestion that Sarajevo's Muslims regularly massacred themselves and then blamed the Serbs; and his denial of the genocide carried out by Serbs at Srebrenica."[5] (Wikipedia)

Perec's first novel, Les Choses (Things: A Story of the Sixties) was awarded the Prix Renaudot in 1965.

His most famous novel, La Vie mode d'emploi (Life a User's Manual), was published in 1978. Its title page describes it as "novels", in the plural, the reasons for which become apparent on reading. La Vie mode d'emploi is a tapestry of interwoven stories and ideas as well as literary and historical allusions, based on the lives of the inhabitants of a fictitious Parisian apartment block. It was written according to a complex plan of writing constraints, and is primarily constructed from several elements, each adding a layer of complexity. The 99 chapters of his 600-page novel, move like a knight's tour of a chessboard around the room plan of the building, describing the rooms and stairwell and telling the stories of the inhabitants. At the end, it is revealed that the whole book actually takes place in a single moment, with a final twist that is an example of "cosmic irony". It was translated into English by David Bellos in 1987. Some critics have cited the work as an example of postmodern fiction.

Perec is noted for his constrained writing: his 300-page novel La disparition (1969) is a lipogram, written without ever using the letter "e". It has been translated into English by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void (1994). The silent disappearance of the letter might be considered a metaphor for the Jewish experience during the Second World War. Since the name "Georges Perec" is full of "e"s, the disappearance of the letter also ensures the author's own "disappearance". His novella Les revenentes (1972) is a complementary univocalic piece in which the letter "e" is the only vowel used. This constraint affects even the title, which would conventionally be spelt Revenantes. An English translation by Ian Monk was published in 1996 as The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex in the collection Three. It has been remarked by Jacques Roubaud that these two novels draw words from two disjoint sets of the French language, and that a third novel would be possible, made from the words not used so far (those containing both "e" and a vowel other than "e").(Wikipedia)

His most famous novel, La Vie mode d'emploi (Life a User's Manual), was published in 1978. Its title page describes it as "novels", in the plural, the reasons for which become apparent on reading. La Vie mode d'emploi is a tapestry of interwoven stories and ideas as well as literary and historical allusions, based on the lives of the inhabitants of a fictitious Parisian apartment block. It was written according to a complex plan of writing constraints, and is primarily constructed from several elements, each adding a layer of complexity. The 99 chapters of his 600-page novel, move like a knight's tour of a chessboard around the room plan of the building, describing the rooms and stairwell and telling the stories of the inhabitants. At the end, it is revealed that the whole book actually takes place in a single moment, with a final twist that is an example of "cosmic irony". It was translated into English by David Bellos in 1987. Some critics have cited the work as an example of postmodern fiction.

Perec is noted for his constrained writing: his 300-page novel La disparition (1969) is a lipogram, written without ever using the letter "e". It has been translated into English by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void (1994). The silent disappearance of the letter might be considered a metaphor for the Jewish experience during the Second World War. Since the name "Georges Perec" is full of "e"s, the disappearance of the letter also ensures the author's own "disappearance". His novella Les revenentes (1972) is a complementary univocalic piece in which the letter "e" is the only vowel used. This constraint affects even the title, which would conventionally be spelt Revenantes. An English translation by Ian Monk was published in 1996 as The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex in the collection Three. It has been remarked by Jacques Roubaud that these two novels draw words from two disjoint sets of the French language, and that a third novel would be possible, made from the words not used so far (those containing both "e" and a vowel other than "e").(Wikipedia)

Claude Ollier (French: [klod ɔlje]; 17 December 1922 – 18 October 2014) was a French writer closely associated with the nouveau roman literary movement.[1] Born in Paris, he was the first winner of the Prix Médicis which he received for his novel La Mise en scène. (Wikipedia)

Le Clézio began writing at the age of seven; his first work was a book about the sea. He achieved very early success at age 23 when his first novel Le Procès-Verbal (The Interrogation) earned him the Prix Renaudot and was shortlisted for the Prix Goncourt.[6] Since then he has published more than thirty-six books, including short stories, novels, essays, two translations on the subject of Native American mythology, and several children's books.

From 1963 to 1975, Le Clézio explored themes such as insanity, language, and writing. He devoted himself to formal experimentation in the wake of such contemporaries as Georges Perec or Michel Butor. His persona was that of an innovator and a rebel, for which he was praised by Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze.

During the late 1970s, Le Clézio's style changed drastically; he abandoned experimentation, and the mood of his novels became less tormented as he used themes like childhood, adolescence, and traveling, which attracted a broader, more popular audience. In 1980, Le Clézio was the first winner of the newly created Grand Prix Paul Morand, awarded by the Académie Française, for his novel, Désert.[15] In 1994, a survey conducted by the French literary magazine Lire showed that 13 percent of the readers considered him to be the greatest living French language writer. (Wikipedia)

From 1963 to 1975, Le Clézio explored themes such as insanity, language, and writing. He devoted himself to formal experimentation in the wake of such contemporaries as Georges Perec or Michel Butor. His persona was that of an innovator and a rebel, for which he was praised by Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze.

During the late 1970s, Le Clézio's style changed drastically; he abandoned experimentation, and the mood of his novels became less tormented as he used themes like childhood, adolescence, and traveling, which attracted a broader, more popular audience. In 1980, Le Clézio was the first winner of the newly created Grand Prix Paul Morand, awarded by the Académie Française, for his novel, Désert.[15] In 1994, a survey conducted by the French literary magazine Lire showed that 13 percent of the readers considered him to be the greatest living French language writer. (Wikipedia)

Thanks to Roland Barthes, Duvert achieved public recognition in 1973 with his novel Paysage de fantaisie (Strange Landscape), which won the Prix Medicis, and which was greeted warmly by critics. For Claude Mauriac the book revealed "gifts and art that the word talent is not enough to express"[4]

In 1974, Duvert expounded his ideology at length in Le Bon Sexe Illustré (Good Sex Illustrated) in which he sharply criticised sex education and the modern western family. Critics praised its humor and his ability to observe the false pretenses of bourgeois society.

With his literary prize money Duvert moved to Morocco, an experience which resulted in his next novel Journal D’un Innocent, (Journal Of An Innocent) published in 1976. Disillusioned by its society, he moved to Thore la Rochette, before settling in Tours. His next novel Quand Mourut Jonathan (When Jonathan Died), published in 1978, was inspired by an earlier vacation with a neglected boy.

Despite his productivity and critical success, Duvert had not achieved the public success he hoped for. To reach a wider audience and raise awareness of his ideas, he decided to write a novel that would incorporate his favorite themes while being less pornographic and written in a classic form. The result was L'Île Atlantique (1979), which received critical raves, and sold somewhat better than his previous works.

In the 1980s, Duvert published L’enfant au masculin (1980), in which he further expounded his sexual philosophy; a novel Un Anneau d’Argent à l’Oreille; and a book of aphorisms Abécédaire Malveillant: unlike his earlier writings, their critical reception was mostly indifferent or poor. By the late 1980s, Duvert was unable to pay the rent on his apartment. With the social mood towards pedophilia hardening in the wake of several abuse scandals, he felt the world had turned against him. He withdrew to his mother's house in Loir-et-Cher, and became a total recluse. Duvert published nothing further, and was largely forgotten. However, in 2005, his novel L'Île Atlantique, which had first appeared in 1979, was adapted for television by Gerard Mordillat.

Tony Duvert's body was discovered at his home in August 2008, several weeks after his death, in a state of decomposition. His death briefly raised his media profile in France again; obituaries noting the quality of his writing, but also reflecting upon the change in official attitudes to child sexuality.

A biography, Tony Duvert. L'Enfant Silencieux. by Gilles Sebhan was published in 2010. It has not yet been translated into English.(Wikipedia)

In 1974, Duvert expounded his ideology at length in Le Bon Sexe Illustré (Good Sex Illustrated) in which he sharply criticised sex education and the modern western family. Critics praised its humor and his ability to observe the false pretenses of bourgeois society.

With his literary prize money Duvert moved to Morocco, an experience which resulted in his next novel Journal D’un Innocent, (Journal Of An Innocent) published in 1976. Disillusioned by its society, he moved to Thore la Rochette, before settling in Tours. His next novel Quand Mourut Jonathan (When Jonathan Died), published in 1978, was inspired by an earlier vacation with a neglected boy.

Despite his productivity and critical success, Duvert had not achieved the public success he hoped for. To reach a wider audience and raise awareness of his ideas, he decided to write a novel that would incorporate his favorite themes while being less pornographic and written in a classic form. The result was L'Île Atlantique (1979), which received critical raves, and sold somewhat better than his previous works.

In the 1980s, Duvert published L’enfant au masculin (1980), in which he further expounded his sexual philosophy; a novel Un Anneau d’Argent à l’Oreille; and a book of aphorisms Abécédaire Malveillant: unlike his earlier writings, their critical reception was mostly indifferent or poor. By the late 1980s, Duvert was unable to pay the rent on his apartment. With the social mood towards pedophilia hardening in the wake of several abuse scandals, he felt the world had turned against him. He withdrew to his mother's house in Loir-et-Cher, and became a total recluse. Duvert published nothing further, and was largely forgotten. However, in 2005, his novel L'Île Atlantique, which had first appeared in 1979, was adapted for television by Gerard Mordillat.

Tony Duvert's body was discovered at his home in August 2008, several weeks after his death, in a state of decomposition. His death briefly raised his media profile in France again; obituaries noting the quality of his writing, but also reflecting upon the change in official attitudes to child sexuality.

A biography, Tony Duvert. L'Enfant Silencieux. by Gilles Sebhan was published in 2010. It has not yet been translated into English.(Wikipedia)

Jean Cayrol (French: [kɛʁɔl]; 6 June 1911 – 10 February 2005) was a French poet, publisher, and member of the Académie Goncourt born in Bordeaux. He is perhaps best known for writing the narration in Alain Resnais's 1955 documentary film, Night and Fog. He was a major contributor to the subversive, philosophical French publication Tel Quel.

In 1941, during the Nazi occupation of France, Cayrol joined the French Resistance, but he was subsequently betrayed, arrested, and sent to the Gusen concentration camp in 1943. He was one of the youngest French inmates at that camp, and consequently was made to do some of the hardest work along with the construction of roads and railways. When Cayrol wanted to die by refusing any further food, his life was saved by Dr. Johann Gruber, the "Saint of Gusen." Gruber gave Cayrol some "Gruber soup" in the washroom of barrack No. 20, and intervened for Cayrol to get him transferred to an easier job. Cayrol thereafter worked at the final-inspection of Steyr-Daimler-Puch at KL Gusen I (the "Georgenmuehle" command), where he was able to write literature during breaks.

Between February 1944 and April 1945, Cayrol created a large volume of poetry at Gusen I. One of his poems from this era is the text for "Chant d' Espoir", which was set to music by a fellow Gusen I inmate, Remy Gillis, in 1944. Alerte aux ombres 1944–1945, a collection of Cayrol's Gusen texts, was published in 1997.[1]

The figure of Lazarus appears many times in Cayrol's work. Having escaped death himself, Cayrol was fascinated and inspired by the story of Lazarus who died, who Jesus returned to life after being dead.[2]

Cayrol founded and edited for ten years (1956–66) the review Ecrire, published by Éditions du Seuil, who had recruited him as an editorial adviser in 1949.[3]

He retired to Bordeaux, where he died at the age of 93. (Wikipedia)

In 1941, during the Nazi occupation of France, Cayrol joined the French Resistance, but he was subsequently betrayed, arrested, and sent to the Gusen concentration camp in 1943. He was one of the youngest French inmates at that camp, and consequently was made to do some of the hardest work along with the construction of roads and railways. When Cayrol wanted to die by refusing any further food, his life was saved by Dr. Johann Gruber, the "Saint of Gusen." Gruber gave Cayrol some "Gruber soup" in the washroom of barrack No. 20, and intervened for Cayrol to get him transferred to an easier job. Cayrol thereafter worked at the final-inspection of Steyr-Daimler-Puch at KL Gusen I (the "Georgenmuehle" command), where he was able to write literature during breaks.

Between February 1944 and April 1945, Cayrol created a large volume of poetry at Gusen I. One of his poems from this era is the text for "Chant d' Espoir", which was set to music by a fellow Gusen I inmate, Remy Gillis, in 1944. Alerte aux ombres 1944–1945, a collection of Cayrol's Gusen texts, was published in 1997.[1]

The figure of Lazarus appears many times in Cayrol's work. Having escaped death himself, Cayrol was fascinated and inspired by the story of Lazarus who died, who Jesus returned to life after being dead.[2]

Cayrol founded and edited for ten years (1956–66) the review Ecrire, published by Éditions du Seuil, who had recruited him as an editorial adviser in 1949.[3]

He retired to Bordeaux, where he died at the age of 93. (Wikipedia)

Blanchot's work is not a coherent, all-encompassing 'theory', since it is a work founded on paradox and impossibility. The thread running through all his writing is the constant engagement with the 'question of literature', a simultaneous enactment and interrogation of the profoundly strange experience of writing. For Blanchot, 'literature begins at the moment when literature becomes a question' (Literature and the Right to Death).[3]

Blanchot draws on the work of the symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé in formulating his conception of literary language as anti-realist and distinct from everyday experience. 'I say flower,' Mallarmé writes in Poetry in Crisis, 'and outside the oblivion to which my voice relegates any shape, insofar as it is something other than the calyx, there arises musically, as the very idea and delicate, the one absent from every bouquet.'[4]

In the everyday use of language, words are the vehicles of ideas. The word 'flower' means flower that refers to flowers in the world. No doubt it is possible to read literature in this way, but literature is more than this everyday use of language. For in literature 'flower' does not just mean flower but many things and it can only do so because the word is independent from what it signifies. This independence, which is passed over in the everyday use of language, is the negativity at the heart of language. The word means something because it negates the physical reality of the thing. Only in this way can the idea arise. The absence of the thing is made good by the presence of the idea. What the everyday use of language steps over to make use of the idea, literature remains fascinated by, the absence that makes it possible. Literary language, therefore, is a double negation, both of the thing and the idea. It is in this space that literature becomes possible where words take on a strange and mysterious reality of their own, and where also meaning and reference remain allusive and ambiguous.

Blanchot's best-known fictional works are Thomas l'Obscur (Thomas the Obscure), an unsettling récit ("[récit] is not the narration of an event, but that event itself, the approach to that event, the place where that event is made to happen")[5] about the experience of reading and loss; Death Sentence; Aminadab and The Most High (about a bureaucrat in a totalitarian state). His central theoretical works are "Literature and the Right to Death" (in The Work of Fire and The Gaze of Orpheus), The Space of Literature, The Infinite Conversation, and The Writing of Disaster.

Themes

Blanchot engages with Heidegger on the question of the philosopher's death, showing how literature and death are both experienced as anonymous passivity, an experience that Blanchot variously refers to as "the Neutral". Unlike Heidegger, Blanchot rejects the possibility of an authentic relation to death, because he rejects the possibility of death, that is to say of the individual's experience of death. He thus rejects, in total, the possibility of understanding and "properly" engaging with it; and this resonates with Levinas' take too.

Blanchot also draws heavily from Franz Kafka, and his fictional work (like his theoretical work) is shot through with an engagement with Kafka's writing.

Blanchot's work was also strongly influenced by his friends Georges Bataille and Emmanuel Levinas. Blanchot's later work in particular is influenced by Levinasian ethics and the question of responsibility to the Other. On the other hand, Blanchot's own literary works, like the famous Thomas the Obscure, heavily influenced Levinas's and Bataille's ideas about the possibility that our vision of reality is blurred because of the use of words (thus making everything you perceive automatically as abstract as words are). This search for the 'real' reality is illustrated by the works of Paul Celan and Stéphane Mallarmé.

The main intellectual biography of Blanchot is by Christophe Bident: Maurice Blanchot, partenaire invisible. (Wikipedia)

Blanchot draws on the work of the symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé in formulating his conception of literary language as anti-realist and distinct from everyday experience. 'I say flower,' Mallarmé writes in Poetry in Crisis, 'and outside the oblivion to which my voice relegates any shape, insofar as it is something other than the calyx, there arises musically, as the very idea and delicate, the one absent from every bouquet.'[4]

In the everyday use of language, words are the vehicles of ideas. The word 'flower' means flower that refers to flowers in the world. No doubt it is possible to read literature in this way, but literature is more than this everyday use of language. For in literature 'flower' does not just mean flower but many things and it can only do so because the word is independent from what it signifies. This independence, which is passed over in the everyday use of language, is the negativity at the heart of language. The word means something because it negates the physical reality of the thing. Only in this way can the idea arise. The absence of the thing is made good by the presence of the idea. What the everyday use of language steps over to make use of the idea, literature remains fascinated by, the absence that makes it possible. Literary language, therefore, is a double negation, both of the thing and the idea. It is in this space that literature becomes possible where words take on a strange and mysterious reality of their own, and where also meaning and reference remain allusive and ambiguous.

Blanchot's best-known fictional works are Thomas l'Obscur (Thomas the Obscure), an unsettling récit ("[récit] is not the narration of an event, but that event itself, the approach to that event, the place where that event is made to happen")[5] about the experience of reading and loss; Death Sentence; Aminadab and The Most High (about a bureaucrat in a totalitarian state). His central theoretical works are "Literature and the Right to Death" (in The Work of Fire and The Gaze of Orpheus), The Space of Literature, The Infinite Conversation, and The Writing of Disaster.

Themes

Blanchot engages with Heidegger on the question of the philosopher's death, showing how literature and death are both experienced as anonymous passivity, an experience that Blanchot variously refers to as "the Neutral". Unlike Heidegger, Blanchot rejects the possibility of an authentic relation to death, because he rejects the possibility of death, that is to say of the individual's experience of death. He thus rejects, in total, the possibility of understanding and "properly" engaging with it; and this resonates with Levinas' take too.

Blanchot also draws heavily from Franz Kafka, and his fictional work (like his theoretical work) is shot through with an engagement with Kafka's writing.

Blanchot's work was also strongly influenced by his friends Georges Bataille and Emmanuel Levinas. Blanchot's later work in particular is influenced by Levinasian ethics and the question of responsibility to the Other. On the other hand, Blanchot's own literary works, like the famous Thomas the Obscure, heavily influenced Levinas's and Bataille's ideas about the possibility that our vision of reality is blurred because of the use of words (thus making everything you perceive automatically as abstract as words are). This search for the 'real' reality is illustrated by the works of Paul Celan and Stéphane Mallarmé.

The main intellectual biography of Blanchot is by Christophe Bident: Maurice Blanchot, partenaire invisible. (Wikipedia)

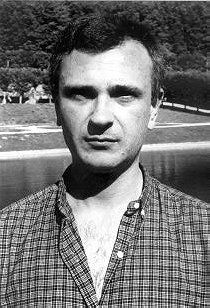

After his father's death in 1950 Yacine worked as a longshoreman in Algiers. He returned to Paris where he would stay until 1959. During this period in Paris he worked with Malek Haddad, developed a relationship with M'hamed Issiakhem, and in 1954, spoke extensively with Bertold Brecht. In 1954, the revue Esprit published Yacine's play 'Le cadavre encerclé', which was staged by Jean-Marie Serreau (fr) but was banned in France. (wikipedia)

'Nedjma' was published in 1956 (and Kateb will not forget the editor's comment: "This is too complicated. In Algeria you've got such pretty sheep, why don't you talk about your sheep?"). During the Algerian war for independence Yacine was forced to travel abroad for a long time due to the harassment he faced from the DST. He lived in numerous places, subsisting as a guest writer or working various odd jobs in France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Yugoslavia and the USSR.

The novel largely eschewing a simple 'realist' style, and written in a highly-sophisticated French which at times passes into poetry, Nedjma has been compared stylistically with contemporary French works of the Nouveau Roman period, although Charles Bonn notes that William Faulkner was a much greater influence on Yacine than any of the Nouveau Roman writers. It has also been read as a response to Albert Camus' famous novel L'Etranger which centres on the apparently irrational murder of an Algerian Arab by a French Pied-Noir.[2]

'Nedjma' was published in 1956 (and Kateb will not forget the editor's comment: "This is too complicated. In Algeria you've got such pretty sheep, why don't you talk about your sheep?"). During the Algerian war for independence Yacine was forced to travel abroad for a long time due to the harassment he faced from the DST. He lived in numerous places, subsisting as a guest writer or working various odd jobs in France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Yugoslavia and the USSR.

The novel largely eschewing a simple 'realist' style, and written in a highly-sophisticated French which at times passes into poetry, Nedjma has been compared stylistically with contemporary French works of the Nouveau Roman period, although Charles Bonn notes that William Faulkner was a much greater influence on Yacine than any of the Nouveau Roman writers. It has also been read as a response to Albert Camus' famous novel L'Etranger which centres on the apparently irrational murder of an Algerian Arab by a French Pied-Noir.[2]

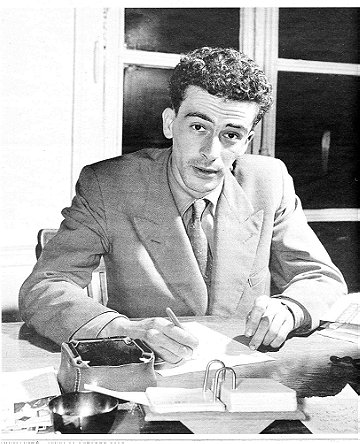

In 1957, Claude Mauriac finally launches into novel writing: All women are fatal (1957), The Dinner in town (1959, receiving the Prix Médicis ), La Marquise went out at five o'clock (1961) and L'Expansion (1963). It brings these novels under the general title: The inner dialogue . Formal research that leads to it will relate to the new novel , which explains its presence in a famous group photo taken in front of the Editions de Minuit in 1959. It was at this time that he invented the concept of "alittérature" which he devotes two books: Contemporary Alittérature (1958) and From literature to the alittérature (1969).

But he dreams of a new work, original, constructed from the abundant material from his diary ongoing. He tried it first with books on Gide ( Conversations with Andre Gide , 1951), on Cocteau ( A thwarted friendship , 1970), and de Gaulle, who has just died ( Another de Gaulle . Journal 1944-1954 , 1970). These last two works are in on-track: The immobile time .

After the death of his father, Francois Mauriac (1 st September 1970), Which slightly precedes that of General de Gaulle, he finally splint, with the resolution to succeed, this will be his great work: The motionless time , almost cinematic montage fragments dated to the Journal . He will publish ten volumes under this generic title from 1972 to 1986. The book, he is full of famous people and it opens one day the author's moods, says a secret design : to glimpse a certain conception of time you could say "mystical" and which appears most clearly in a volume written in the margin of the series, but that is the key and whose title is significant: sometimes Eternity .

This meticulous and ambitious work editing "romance" of a new kind does not prevent Claude Mauriac to continue his literary creation in other areas: theater, mounted by Nicolas Bataille and Laurent Terzieff , and novels (including Zabé , Gallimard, 1984), it brings together under the general title: The Infiltration of the invisible . Or pursue his journalistic activities. Or participate in the Mask Feather and the deliberations of the jury of Prix Médicis or that of the Louis Delluc Prize which he belongs. Especially not to lead advocacy on behalf of prisoners, "badly housed" or leading figures in company immigrants like those of Michel Foucault , of Gilles Deleuze or Emmanuelli 4 . We find echoes in Le Temps immobile , but even more in a book also mounted from the Journal: A certain rage (1977). (Wikipedia)

But he dreams of a new work, original, constructed from the abundant material from his diary ongoing. He tried it first with books on Gide ( Conversations with Andre Gide , 1951), on Cocteau ( A thwarted friendship , 1970), and de Gaulle, who has just died ( Another de Gaulle . Journal 1944-1954 , 1970). These last two works are in on-track: The immobile time .

After the death of his father, Francois Mauriac (1 st September 1970), Which slightly precedes that of General de Gaulle, he finally splint, with the resolution to succeed, this will be his great work: The motionless time , almost cinematic montage fragments dated to the Journal . He will publish ten volumes under this generic title from 1972 to 1986. The book, he is full of famous people and it opens one day the author's moods, says a secret design : to glimpse a certain conception of time you could say "mystical" and which appears most clearly in a volume written in the margin of the series, but that is the key and whose title is significant: sometimes Eternity .

This meticulous and ambitious work editing "romance" of a new kind does not prevent Claude Mauriac to continue his literary creation in other areas: theater, mounted by Nicolas Bataille and Laurent Terzieff , and novels (including Zabé , Gallimard, 1984), it brings together under the general title: The Infiltration of the invisible . Or pursue his journalistic activities. Or participate in the Mask Feather and the deliberations of the jury of Prix Médicis or that of the Louis Delluc Prize which he belongs. Especially not to lead advocacy on behalf of prisoners, "badly housed" or leading figures in company immigrants like those of Michel Foucault , of Gilles Deleuze or Emmanuelli 4 . We find echoes in Le Temps immobile , but even more in a book also mounted from the Journal: A certain rage (1977). (Wikipedia)

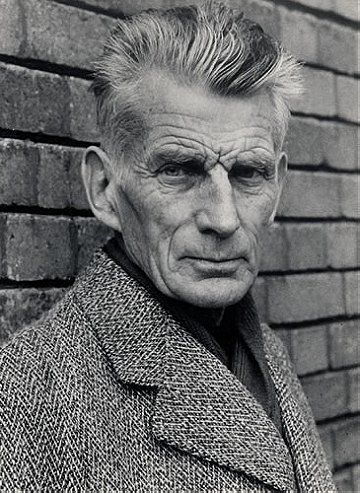

Any Beckett's work is crossed by an acute understanding of the tragedy of birth: "You're on earth, there is no remedy! "Said Hamm, the main protagonist of Endgame . This life is still living. For, as it is written at the end of the Unspeakable , "we must go on, I can not go, I will continue."

The work is a testimony to the end of a world. Perceptive witness to his times, Samuel Beckett announced the end of art ( Waiting for Godot ) and the end of an era marked by the rule in Europe, French culture ( Endgame ), long before these themes become fashionable. Art can no longer try to beautify the world as in the past. A certain idea of art comes to an end. Beckett points out the hypocrisy in Happy Days . Winnie delights of a world experiencing a daily "enrichment of knowledge", while, in his hand, his companion Willie takes a pornographic postcard.

The life of Beckett writer can be schematically divided into three parts: the first, the first works, until the end of the Second World War ; the second, from 1945 to 1960 , during which he wrote his most famous pieces; and finally, from 1960 to his death, a period which saw the number of its publications decline, and style become increasingly minimalist. (Wikipedia)

The work is a testimony to the end of a world. Perceptive witness to his times, Samuel Beckett announced the end of art ( Waiting for Godot ) and the end of an era marked by the rule in Europe, French culture ( Endgame ), long before these themes become fashionable. Art can no longer try to beautify the world as in the past. A certain idea of art comes to an end. Beckett points out the hypocrisy in Happy Days . Winnie delights of a world experiencing a daily "enrichment of knowledge", while, in his hand, his companion Willie takes a pornographic postcard.

The life of Beckett writer can be schematically divided into three parts: the first, the first works, until the end of the Second World War ; the second, from 1945 to 1960 , during which he wrote his most famous pieces; and finally, from 1960 to his death, a period which saw the number of its publications decline, and style become increasingly minimalist. (Wikipedia)

Robert Pinget (Geneva, July 19, 1919 – Tours, August 25, 1997) was a major avant-garde French writer, born in Switzerland, who wrote several novels and other prose pieces that drew comparison to Beckett and other major Modernist writers. He was also associated with the nouveau roman movement.

In 1962, Germaine Tailleferre of Les Six set eleven of his poems in a song cycle entitled "Pancarte pour Une Porte D'Entrée" (roughly translated as "Handbill for an Entrance") for medium voice and piano, commissioned by the American Soprano and Arts Patron Alice Swanson Esty.

A translation of one of his best known works, The Inquisitory (1962), was recently republished by the Dalkey Archive Press.(Wikipedia)

In 1962, Germaine Tailleferre of Les Six set eleven of his poems in a song cycle entitled "Pancarte pour Une Porte D'Entrée" (roughly translated as "Handbill for an Entrance") for medium voice and piano, commissioned by the American Soprano and Arts Patron Alice Swanson Esty.

A translation of one of his best known works, The Inquisitory (1962), was recently republished by the Dalkey Archive Press.(Wikipedia)

Added to

Related lists

Sports ...NFL Power Ranking...2017 NFL Schedule

32 item list by william maxey 83

14 votes 4 comments

4 comments

32 item list by william maxey 83

14 votes

4 comments

4 comments

View more top voted lists

Login

Login