Reference...

Sort by:

Showing 1-50 of 339

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

The Birth of a Nation (1915)

Simultaneously one of the most revered and most reviled films ever made, D.W. Griffith's The Birth of a Nation is important for the very reasons that prompt both of those divergent reactions. In fact, rarely has a film so equally deserved such praise and scorn, which in many ways raises the film's estimation not just in the annals of cinema but as an essential historic artifact (some might say relic).

Though it was based on Thomas Dixon's explicitly racist play The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, by many accounts Griffith was indifferent to the racist bent of the subject matter. Just how complicit that makes him in delivering its ugly message has been cause for almost a century of debate. However, there has been no debate concerning the film's technical and artistic merits. Griffith was, as usual, more interested in the possibilities of the medium than the message, and in this regard he set the standards for modern Hollywood.

Most overtly, The Birth of a Nation was the first real historical epic, proving that even in the silent era audiences were willing to sit through a nearly three-hour drama. But with countless artistic innovations, Griffith essentially created contemporary film language, and although elements of The Birth of a Nation may seem quaint or dated by contemporary standards, virtually every film is beholden to it in one way, shape, or form. Griffith introduced the use of dramatic close-ups, tracking shots, and other expressive camera movements; parallel action sequences, crosscutting, and other editing techniques; and even the first orchestral score. It's a shame all these groundbreaking elements were attached to a story of such dubious value.

The first half of the film begins before the Civil War, explaining the introduction of slavery to America before jumping into battle. Two families, the nothern Stonemans and the southern Camerons, are introduced. The story is told through these two families and often their servants, epitomizing the worst racial stereotypes. As the nation is torn apart by war, the slaves and their abolitionist supporters are seen as the destructive force behind it all.

The film's racism grows even worse in its second half, set during Reconstruction and featuring the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, introduced as the picture's would-be heroes. The fact that Griffith jammed a love story in the midst of his recreated race war is absolutely audacious. It's thrilling and disturbing, often at the same time.

The Birth of a Nation is no doubt a powerful piece of propaganda, albeit one with a stomach-churning political message. Only the puritanical Ku Klux Klan can maintain the unity of the nation, it seems to be saying, so is it any wonder that even at the time the film was met with outrage? It was protested by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), sparked riots, and later forced Griffith himself to answer criticisms with his even more ambitious Intolerance (1916). Still, the fact that The Birth of a Nation remains respected and studied to this day--despite its subject matter--reveals its lasting importance. [190 min.]

Though it was based on Thomas Dixon's explicitly racist play The Clansman: An Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan, by many accounts Griffith was indifferent to the racist bent of the subject matter. Just how complicit that makes him in delivering its ugly message has been cause for almost a century of debate. However, there has been no debate concerning the film's technical and artistic merits. Griffith was, as usual, more interested in the possibilities of the medium than the message, and in this regard he set the standards for modern Hollywood.

Most overtly, The Birth of a Nation was the first real historical epic, proving that even in the silent era audiences were willing to sit through a nearly three-hour drama. But with countless artistic innovations, Griffith essentially created contemporary film language, and although elements of The Birth of a Nation may seem quaint or dated by contemporary standards, virtually every film is beholden to it in one way, shape, or form. Griffith introduced the use of dramatic close-ups, tracking shots, and other expressive camera movements; parallel action sequences, crosscutting, and other editing techniques; and even the first orchestral score. It's a shame all these groundbreaking elements were attached to a story of such dubious value.

The first half of the film begins before the Civil War, explaining the introduction of slavery to America before jumping into battle. Two families, the nothern Stonemans and the southern Camerons, are introduced. The story is told through these two families and often their servants, epitomizing the worst racial stereotypes. As the nation is torn apart by war, the slaves and their abolitionist supporters are seen as the destructive force behind it all.

The film's racism grows even worse in its second half, set during Reconstruction and featuring the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, introduced as the picture's would-be heroes. The fact that Griffith jammed a love story in the midst of his recreated race war is absolutely audacious. It's thrilling and disturbing, often at the same time.

The Birth of a Nation is no doubt a powerful piece of propaganda, albeit one with a stomach-churning political message. Only the puritanical Ku Klux Klan can maintain the unity of the nation, it seems to be saying, so is it any wonder that even at the time the film was met with outrage? It was protested by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), sparked riots, and later forced Griffith himself to answer criticisms with his even more ambitious Intolerance (1916). Still, the fact that The Birth of a Nation remains respected and studied to this day--despite its subject matter--reveals its lasting importance. [190 min.]

ToonHead2102's rating:

Louis Feuillade's legendary opus has been cited as a landmark movie serial, a precursor of the deep-focus aesthetic later advanced by Jean Renoir and Orson Welles, and a close cousin to the surrealist movement, but its strongest relationship is to the development of the movie thriller. Segmented into ten loosely connected parts that lack cliffhanger endings, vary widely in length, and were released at irregular intervals, Les Vampires falls somewhere between a film series and a film series. The convoluted, often inconsistent plot centers on a flamboyant gang of Parisian criminals, the Vampires, and their dauntless opponent, the reporter Philippe Guerande (Edouard Mathe).

The Vampires, masters of disguise who often dress in black hoods and leotards while carrying out their crimes, are led by four successive "Grand Vampires," each killed off in turn, each faithfully served by the vampish Irma Vep (her name an anagram of Vampire), who constitutes the heart and soul not only of the Vampires but also of Les Vampires itself. Portrayed with voluptuous vitality by Musidora, who became a star as a result, Irma is the film's most attractive character, clearly surpassing the pallid hero Guerande and his hammy comic sidekick Mazamette (Marcel Levesque). Her charisma undercuts the film's good-versus-evil theme and contributes to its somewhat amoral tone, reinforced by the way the good guys and the bad guys use the same duplicitous methods and by the disturbingly ferocious slaughter of the Vampires at the end.

Much like the detective story and the haunted-house thriller, Les Vampires creates a sturdy-looking world of bourgeois oder while also undermining it. The thick floors and walls of each chateau and hotel become porous with trap doors and secret panels. Massive fireplaces serve as thoroughfares for assassins and thieves, who scurry over Paris rooftops and shimmy up and down drainpipes like monkeys. Taxicabs bristle with stowaways on their roofs and disclose false floors to eject fugutives into convenient manholes. At one point, the hero unsuspectingly sticks his head out the window of his upper-story apartment, only to be looped around the neck by a wire snare wielded from below; he is yanked down to the street, bundled into a large basket, and whisked off by a taxi in less than it takes to say "Irma Vep!" In another scene, a wall with a fireplace opens up to disgorge a large cannon, which slides to the window and lobs shells into a nearby cabaret.

Reinforcing this atmosphere of capricious stability, the plot is built around a series of tour de force reversals, involving deceptive appearances on both sides of the law: "dead" characters come to life, pillars of society (a priest, a judge, a policeman) turn out to be Vampires, and Vampires are revealed to be law enforcers operating in disguise. It is Feuillade's ability to create, on an extensive and imaginative scale, a double world--at once weighty and dreamlike, recognizably familiar and excitingly strange--that is of central importance to the evolution of the movie thriller and marks him as a major pioneer of the form. [440 min.]

The Vampires, masters of disguise who often dress in black hoods and leotards while carrying out their crimes, are led by four successive "Grand Vampires," each killed off in turn, each faithfully served by the vampish Irma Vep (her name an anagram of Vampire), who constitutes the heart and soul not only of the Vampires but also of Les Vampires itself. Portrayed with voluptuous vitality by Musidora, who became a star as a result, Irma is the film's most attractive character, clearly surpassing the pallid hero Guerande and his hammy comic sidekick Mazamette (Marcel Levesque). Her charisma undercuts the film's good-versus-evil theme and contributes to its somewhat amoral tone, reinforced by the way the good guys and the bad guys use the same duplicitous methods and by the disturbingly ferocious slaughter of the Vampires at the end.

Much like the detective story and the haunted-house thriller, Les Vampires creates a sturdy-looking world of bourgeois oder while also undermining it. The thick floors and walls of each chateau and hotel become porous with trap doors and secret panels. Massive fireplaces serve as thoroughfares for assassins and thieves, who scurry over Paris rooftops and shimmy up and down drainpipes like monkeys. Taxicabs bristle with stowaways on their roofs and disclose false floors to eject fugutives into convenient manholes. At one point, the hero unsuspectingly sticks his head out the window of his upper-story apartment, only to be looped around the neck by a wire snare wielded from below; he is yanked down to the street, bundled into a large basket, and whisked off by a taxi in less than it takes to say "Irma Vep!" In another scene, a wall with a fireplace opens up to disgorge a large cannon, which slides to the window and lobs shells into a nearby cabaret.

Reinforcing this atmosphere of capricious stability, the plot is built around a series of tour de force reversals, involving deceptive appearances on both sides of the law: "dead" characters come to life, pillars of society (a priest, a judge, a policeman) turn out to be Vampires, and Vampires are revealed to be law enforcers operating in disguise. It is Feuillade's ability to create, on an extensive and imaginative scale, a double world--at once weighty and dreamlike, recognizably familiar and excitingly strange--that is of central importance to the evolution of the movie thriller and marks him as a major pioneer of the form. [440 min.]

The Birth of a Nation and Intolerance are, rightly, Griffith's most renowned films, remembered for their remarkable manipulations of story and editing. But another of his films, 1919's Broken Blossoms, has always stood out as among his very best, and it is surely his most beautiful.

Along with William Beaudine's glorious Mark Pickford vehicle Sparrows, Broken Blossoms exemplifies what was known in Hollywood as the "soft style." This was the ultimate in glamour photography: Cinematographers used every available device--powder makeup, specialized lighting instruments, oil smeared on the lens, even immense sheets of diaphanous gauze hanging from the studio ceiling--to soften, highlight, and otherwise accentuate the beauty of their stars. In Broken Blossoms, the face of the immortal Lillian Gish literally glows with a lovely, unearthly luminescence, outshining all other elements on the screen.

The beauty of Broken Blossoms must be experienced, for it is truly stunning. Gish and her costar, the excellent Richard Barthelmess, glide hauntedly through a London landscape defined by fog, eerie alleyway lights, and arcane, "Orientalist" sets. The film's simple story of forbidden love is complemented perfectly by the gorgeous, mysterious production design, created by Joseph Stringer. No other film looks like Broken Blossoms.

The collaboration between Griffith and Gish is one of American cinema's most fruitful: the two also worked together on Intolerance, The Birth of a Nation, Orphans of the Storm, and Way Down East, in addition to dozens of shorts. Surely this director-actor collaboration ranks with Scorsese-De Niro, Kurosawa-Mifune, and Leone-Eastwood; indeed it is the standard by which all others should be judged. Griffith finds a perfect balance between the story's mundanity and the production's seedy lavishness (much of the film takes place in opium dens and dockside dives). It is the tension between the everyday and the extraordinary that drives on Broken Blossoms, securing its place in film history. [90 min.]

Along with William Beaudine's glorious Mark Pickford vehicle Sparrows, Broken Blossoms exemplifies what was known in Hollywood as the "soft style." This was the ultimate in glamour photography: Cinematographers used every available device--powder makeup, specialized lighting instruments, oil smeared on the lens, even immense sheets of diaphanous gauze hanging from the studio ceiling--to soften, highlight, and otherwise accentuate the beauty of their stars. In Broken Blossoms, the face of the immortal Lillian Gish literally glows with a lovely, unearthly luminescence, outshining all other elements on the screen.

The beauty of Broken Blossoms must be experienced, for it is truly stunning. Gish and her costar, the excellent Richard Barthelmess, glide hauntedly through a London landscape defined by fog, eerie alleyway lights, and arcane, "Orientalist" sets. The film's simple story of forbidden love is complemented perfectly by the gorgeous, mysterious production design, created by Joseph Stringer. No other film looks like Broken Blossoms.

The collaboration between Griffith and Gish is one of American cinema's most fruitful: the two also worked together on Intolerance, The Birth of a Nation, Orphans of the Storm, and Way Down East, in addition to dozens of shorts. Surely this director-actor collaboration ranks with Scorsese-De Niro, Kurosawa-Mifune, and Leone-Eastwood; indeed it is the standard by which all others should be judged. Griffith finds a perfect balance between the story's mundanity and the production's seedy lavishness (much of the film takes place in opium dens and dockside dives). It is the tension between the everyday and the extraordinary that drives on Broken Blossoms, securing its place in film history. [90 min.]

Way Down East (1920)

Soon after The Birth of a Nation (1915), one of the most profitable films ever made, D.W. Griffith saw his career go into decline, mostly as a result of his inability to adapt to the changing desires of the filmgoing public. Griffith had specialized in bringing Victorian melodrama, with its tales of threatened female innocence, to the screen. By 1920, however, audiences had begun to show less interest in virtue rescued or preserved. It was therefore a surprise that Griffith decided to adapt for the screen the 1890s stage melodrama Way Down East, not to mention that he was able to breathe new life into the story and make it into a very successful film.

Anna Moore (Lillian Gish) leaves her small New England village to live with wealthier relatives in Boston. There she comes under the spell of an attractive young man named Sanderson (Lowell Sherman), who tricks her into sleeping with him by staging a phony marriage. He then sends her back to New England, with a command to keep silent about their nuptials. Upon discovering she is pregnant, Anna contacts him, only to learn the bitter truth. Nothing but disaster follows. Her mother dies. So does her child. She is driven away from the rooming house where she had taken shelter because the landlady suspects she isn't married. Luckily, she finds a new position at a nearby farm owned by Squire Barlett (Burt McIntosh), but Sanderson lives not far away. At the farm, Anna meets the squire's son David (Richard Barthelmess), and the two soon fall in love.

But Anna's past catches up with her. Dismissed from the squire's employ, she wanders off into a terrible snowstorm and finds herself on a frozen river. Floating away on an ice floe toward huge falls, Anna is rescued at the last minute by David. Sanderson's villainy is exposed, and Anna reconciles with the repentant squire. The film ends with their wedding. The dramatic parts of Way Down East are kept lively by Griffith's pacing of the narrative and the affecting performances of an able cast. The film's action conclusion, however, shows the director at his finest, both in the shooting of the sequence (parts were filmed on a frozen Vermont river) and in the editing, which is fast paced and thrilling. [100 min.]

Anna Moore (Lillian Gish) leaves her small New England village to live with wealthier relatives in Boston. There she comes under the spell of an attractive young man named Sanderson (Lowell Sherman), who tricks her into sleeping with him by staging a phony marriage. He then sends her back to New England, with a command to keep silent about their nuptials. Upon discovering she is pregnant, Anna contacts him, only to learn the bitter truth. Nothing but disaster follows. Her mother dies. So does her child. She is driven away from the rooming house where she had taken shelter because the landlady suspects she isn't married. Luckily, she finds a new position at a nearby farm owned by Squire Barlett (Burt McIntosh), but Sanderson lives not far away. At the farm, Anna meets the squire's son David (Richard Barthelmess), and the two soon fall in love.

But Anna's past catches up with her. Dismissed from the squire's employ, she wanders off into a terrible snowstorm and finds herself on a frozen river. Floating away on an ice floe toward huge falls, Anna is rescued at the last minute by David. Sanderson's villainy is exposed, and Anna reconciles with the repentant squire. The film ends with their wedding. The dramatic parts of Way Down East are kept lively by Griffith's pacing of the narrative and the affecting performances of an able cast. The film's action conclusion, however, shows the director at his finest, both in the shooting of the sequence (parts were filmed on a frozen Vermont river) and in the editing, which is fast paced and thrilling. [100 min.]

A celebrated world success in its initial release, The Phantom Carriage not only centered director-screenwriter-actor Victor Sjostrom and the Swedish silent cinema's fame but also had a well-documented, artistic influence on many great directors and producers. The most well-known element of the film is undoubtedly the representation of the spiritual world as a tormented limbo between heaven and earth. The scene in which the protagonist--the hateful and self-destructive alcoholic David Holm (Sjostrom)--wakes up at the chime of midnight on New Year's Eve only to stare at his own corpse, knowing that he is condemned to hell, is one of the most quoted scenes in cinema history.

Made in a simple but time-consuming and meticulously staged series of double exposures, the filmmaker, his photographer, and a lab manager created a three-dimensional illusion of a ghostly world that went beyond anything previously seen at the cinema. More important perhaps was the film's complex but readily accessible narration via a series of flashbacks--and even flashbacks-within-flashbacks-that elevated this gritty tale of poverty and degradation to poetic excellence.

Looking back at Sjostrom's career, The Phantom Carriage is a theological and philosophical extension of the social themes introduced in his controversial breakthrough Ingeborg Holm (1913). Both films depict the step-by-step destruction of human dignity in a cold and heartless society, driving its victims into brutality and insanity. The connection is stressed by the presence of Hilda Borgstrom, unforgettable as Ingeborg Holm and now in the role of a tortured wife--another desperate Mrs. Holm. She is yet again playing a compassionate but poor mother on her way to suicide of a life in the mental asylum.

The religious naivete at the heart of Selma Lagerlof's faithfully adapted novel might draw occasional laughter from a secular audience some eighty years later, but the subdued, "realist" acting and the dark fate of the main characters, which almost comes to its logical conclusion, save for a melodramatic finale, never fails to impress. [93 min.]

Made in a simple but time-consuming and meticulously staged series of double exposures, the filmmaker, his photographer, and a lab manager created a three-dimensional illusion of a ghostly world that went beyond anything previously seen at the cinema. More important perhaps was the film's complex but readily accessible narration via a series of flashbacks--and even flashbacks-within-flashbacks-that elevated this gritty tale of poverty and degradation to poetic excellence.

Looking back at Sjostrom's career, The Phantom Carriage is a theological and philosophical extension of the social themes introduced in his controversial breakthrough Ingeborg Holm (1913). Both films depict the step-by-step destruction of human dignity in a cold and heartless society, driving its victims into brutality and insanity. The connection is stressed by the presence of Hilda Borgstrom, unforgettable as Ingeborg Holm and now in the role of a tortured wife--another desperate Mrs. Holm. She is yet again playing a compassionate but poor mother on her way to suicide of a life in the mental asylum.

The religious naivete at the heart of Selma Lagerlof's faithfully adapted novel might draw occasional laughter from a secular audience some eighty years later, but the subdued, "realist" acting and the dark fate of the main characters, which almost comes to its logical conclusion, save for a melodramatic finale, never fails to impress. [93 min.]

Orphans of the Storm (1921)

The last of D.W. Griffith's sweeping historical melodramas, Orphans of the Storm tells the story of two young girls caught in the turmoil of the French Revolution. Lillian and Dorothy Gish are Henriette and Louise Girard, two babies who become "sisters" when Henriette's impoverished father, thinking to abandon his daughter in a church, finds Louise and, moved by pity, brings both girls home to raise. Unfortunately, they are left orphaned at an early age when their parents die of the plague. Louise is left blind by the disease, and so the girls make their way to Paris in seach of her cure. There they are separated. Henriette, kidnapped by the henchmen of an evil aristocrat, is befriended by a handsome nobleman, Vaudrey (Joseph Schildkraut). Louise is rescued by a kind young man after she falls into the River Seine but, brought to his house, she is put to work by the man's cruel brother. Adventures follow, including imprisonment in the Bastille, being condemned to death during the Reign of Terror, and saved from the guillotine by the politician Danton (Monte Blue), whose speech advocating the end of such bloodshed is one of the film's most impassioned moments.

Although Orphans of the Storm is based on a play that had been successful in the preceding decade, Griffith wrote the script during shooting. Despite the resulting complications, the film is a masterpiece of beautiful staging and acting, with the Gish sisters turning in what are perhaps the finest performances of their careers. [150 min.]

Although Orphans of the Storm is based on a play that had been successful in the preceding decade, Griffith wrote the script during shooting. Despite the resulting complications, the film is a masterpiece of beautiful staging and acting, with the Gish sisters turning in what are perhaps the finest performances of their careers. [150 min.]

Dr. Mabuse: The Gambler (1922)

This two-part epic was a major commercial success in Germany in 1922, doubtless because of its everything-including-the-kitchen-sink approach, scrambling thrills, horrors, politics, satire, sex (including nude scenes!), magic, psychology, art, violence, low comedy, and special effects. Whereas the escapades of Fantomas (and even Fu Manchu) belong to that netherworld between the surreal and the pulpy, Dr. Mabuse was intended from the outset not merely as flamboyant thriller but as pointed editorial, using the figure of the master-of-disguise supercriminal to embody the real evils of its era.

The subtitles of each of the film's two parts, harping on about "our time," underline the point made obvious in the opening act, in which Mabuse's gang steals a Swiss-Dutch trade agreement--not to make use of the secret information, but to create a momentary stock market panic that allows Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), in disguise as a cartoon plutocrat with top hat and fur coat, to make a fast fortune. He also employs a band of blind men as forgers, contributing to the feeling that German audiences at the time had that money was worthless (Mabuse sees this coming and orders his men to switch over to forging U.S. currency, since even real marks aren't worth as much as counterfeit dollars).

The film's eponymous villain shuffles photographs as if they were a deck of cards, selecting his identity for the day from various disguises, but it is nearly two hours before his "real" name is confirmed--by which time, we have seen Mabuse in several other guises, from respected psychiatrist to degenerate gambler to hotel manager. In Part 2, he appears as a one-armed stage illusionist, and finally loses his grip on the fragile core of his identity to become a ranting madman, tormented by the hollow-cheeked specters of those he has killed and, in a moment that still startles, by the creaking-to-life of vast, grotesque statues and bits of machinery in his final lair. Director Fritz Lang, and others, would return to Mabuse, still embodying the ills of the age--notably in the early talkie Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (1933) and the 1961 high-tech surveillance melodrama The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse. [95 & 100 min.]

The subtitles of each of the film's two parts, harping on about "our time," underline the point made obvious in the opening act, in which Mabuse's gang steals a Swiss-Dutch trade agreement--not to make use of the secret information, but to create a momentary stock market panic that allows Mabuse (Rudolf Klein-Rogge), in disguise as a cartoon plutocrat with top hat and fur coat, to make a fast fortune. He also employs a band of blind men as forgers, contributing to the feeling that German audiences at the time had that money was worthless (Mabuse sees this coming and orders his men to switch over to forging U.S. currency, since even real marks aren't worth as much as counterfeit dollars).

The film's eponymous villain shuffles photographs as if they were a deck of cards, selecting his identity for the day from various disguises, but it is nearly two hours before his "real" name is confirmed--by which time, we have seen Mabuse in several other guises, from respected psychiatrist to degenerate gambler to hotel manager. In Part 2, he appears as a one-armed stage illusionist, and finally loses his grip on the fragile core of his identity to become a ranting madman, tormented by the hollow-cheeked specters of those he has killed and, in a moment that still startles, by the creaking-to-life of vast, grotesque statues and bits of machinery in his final lair. Director Fritz Lang, and others, would return to Mabuse, still embodying the ills of the age--notably in the early talkie Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse (1933) and the 1961 high-tech surveillance melodrama The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse. [95 & 100 min.]

The Thief of Bagdad marked the culmination of Douglas Fairbanks's career as the ultimate hero of swashbuckling costume spectacles. It is also one of the most visually breathtaking movies ever made, a unique and integral conception by a genius of film design, William Cameron Menzies. Building his mythical Bagdad on a six-and-a-half-acre site (the biggest in Hollywood history), Menzies created a shimmering, magical world, as insubstantial yet as real and haunting as a dream, with its reflective floors, soaring minarets, flying carpets, ferocious dragons, and winged horses.

As Ahmed the Thief in quest of his Princess, Fairbanks--bare chested and with clinging silken garments--explored a new sensuous eroticism in his screen persona, and found an appropriate costar in Anna May Wong, as the Mongol slave girl. Although the nominal director was the gifted and able Raoul Walsh, the overall concept for The Thief of Bagdad was Fairbanks's own, as producer, writer, star, stuntman, and showman of unbounded ambition. (Side note: the uncredited Persian Prince in the film is played by a woman, Mathilde Comont.) [155 min.]

As Ahmed the Thief in quest of his Princess, Fairbanks--bare chested and with clinging silken garments--explored a new sensuous eroticism in his screen persona, and found an appropriate costar in Anna May Wong, as the Mongol slave girl. Although the nominal director was the gifted and able Raoul Walsh, the overall concept for The Thief of Bagdad was Fairbanks's own, as producer, writer, star, stuntman, and showman of unbounded ambition. (Side note: the uncredited Persian Prince in the film is played by a woman, Mathilde Comont.) [155 min.]

ToonHead2102's rating:

The Last Laugh (1924) (1924)

Despite a ludicrously unconvincing happy ending grafted on at the insistence of UFA, F.W. Murnau's The Last Laugh remains a very impressive attempt to tell a story without the use of intertitles. the plot itself is nothing special--a hotel commissionaire, humiliated by his loss in status when he is demoted to lavatory attendant because of his advancing years, sinks so low that he is tempted to steal back his beloved uniform (the symbol of his professional pride). In some respects the film is merely a vehicle for one of Emil Janning's typically grandstand performances.

Above and beyond this somewhat pathetic parable, however, exists one of Murnau's typically eloquent explorations of cinematic space: the camera prowls around with astonishing fluidity, articulating the protagonist's relationship with the world as it follows him around the hotel, the city streets, and his home in the slum tenements. Some of the camera work is "subjective," as when his drunken perceptions are rendered by optical distortion; at other times, it is the camera's mobility that is evocative, as when it passes through the revolving doors that serve as a symbol of destiny. The dazzling technique on display may, in fact, be rather too grand for the simple story of one old man, yet there is no denying the virtuosity either of Murnau's mise-en-scene or of Karl Freund's camera work. [77 min.]

Above and beyond this somewhat pathetic parable, however, exists one of Murnau's typically eloquent explorations of cinematic space: the camera prowls around with astonishing fluidity, articulating the protagonist's relationship with the world as it follows him around the hotel, the city streets, and his home in the slum tenements. Some of the camera work is "subjective," as when his drunken perceptions are rendered by optical distortion; at other times, it is the camera's mobility that is evocative, as when it passes through the revolving doors that serve as a symbol of destiny. The dazzling technique on display may, in fact, be rather too grand for the simple story of one old man, yet there is no denying the virtuosity either of Murnau's mise-en-scene or of Karl Freund's camera work. [77 min.]

The Great White Silence (2011)

Herbert Ponting's footage of Captain Scott's ill-fated attempt to lead the first team to the South Pole was never intended as a film. It was the director's skill as a photographer that guaranteed him passage on the Terra Nova. His images were to be the centerpiece of Scott's lecture series, which would travel the world and recoup some costs from the expedition. But with the death of Scott and his team, Ponting returned to Britain and devoted the rest of his life to celebrating the heroism of these pioneers.

The director had assembled a detailed record of daily life on the ship, as Scott--a fleeting presence throughout the film--and his men prepared for their epic journey. With time to kill during preparations, Ponting filmed Ross Island, the mission's base camp, often going to extraordinary lengths--and great personal danger--to capture the most arresting images. Once Scott embarked on his mission, which dominates the last section of the film, Ponting blends life as it continues on Ross Island with animated sequences, mapping the group's final journey.

The completed film was unsuccessful commercially, even when released with a soundtrack, as 90 South (1933). In 2011, the British Film Institute released a restoration of the film, featuring an atmospheric score by Simon Fisher Turner. This pristine version highlights Ponting's incredible achievement in capturing the glory and the danger of those individuals who defined the "Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration." [108 min.]

The director had assembled a detailed record of daily life on the ship, as Scott--a fleeting presence throughout the film--and his men prepared for their epic journey. With time to kill during preparations, Ponting filmed Ross Island, the mission's base camp, often going to extraordinary lengths--and great personal danger--to capture the most arresting images. Once Scott embarked on his mission, which dominates the last section of the film, Ponting blends life as it continues on Ross Island with animated sequences, mapping the group's final journey.

The completed film was unsuccessful commercially, even when released with a soundtrack, as 90 South (1933). In 2011, the British Film Institute released a restoration of the film, featuring an atmospheric score by Simon Fisher Turner. This pristine version highlights Ponting's incredible achievement in capturing the glory and the danger of those individuals who defined the "Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration." [108 min.]

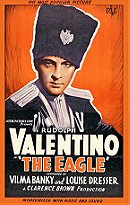

The Eagle (1925)

Rudolph Valentino will best be remembered as one of cinema's first heartthrobs. His swarthy looks seduced millions and his premature death, at the age of thirty-one, prompted scenes of pandemonium. He is perhaps less remembered for his comic skills, which are on display in The Eagle. In the place of brooding romance is an engaging romp, often parodying the star's persona, with Valentino game enough to play along.

He plays Vladimir Dobrovsky, a Cossack serving in the Russian army, whose act of bravery in stopping a runaway carriage and saving its pretty occupant (Vilma Banky) attracts the attention of the ageing Czarina (Louise Dresser). She attempts to seduce Dobrovsky, who runs away, escaping to his country home only to discover it has been overrun by a villainous braggart. The man's daughter is the very woman Dobrovsky had saved. Donning the disguise of the Black Eagle in order to terrorize the man who took his father's land, and a French tutor so that he can be close to the villain's daughter, Dobrovsky finds himself torn between his heart and his family's honor.

Director Clarence Brown employs a number of visual flourishes, including an elegant tracking shot over a vast banquet of food, which elevates the quality of the film. Although the narrative is uneven--the family's honor is never really restored and the Czarina is perhaps a little too forgiving--The Eagle is nevertheless a light-hearted frolic whose balance of comedy and drama foreshadows later action films such as The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and The Mark of Zorro (1940). [80 min.]

He plays Vladimir Dobrovsky, a Cossack serving in the Russian army, whose act of bravery in stopping a runaway carriage and saving its pretty occupant (Vilma Banky) attracts the attention of the ageing Czarina (Louise Dresser). She attempts to seduce Dobrovsky, who runs away, escaping to his country home only to discover it has been overrun by a villainous braggart. The man's daughter is the very woman Dobrovsky had saved. Donning the disguise of the Black Eagle in order to terrorize the man who took his father's land, and a French tutor so that he can be close to the villain's daughter, Dobrovsky finds himself torn between his heart and his family's honor.

Director Clarence Brown employs a number of visual flourishes, including an elegant tracking shot over a vast banquet of food, which elevates the quality of the film. Although the narrative is uneven--the family's honor is never really restored and the Czarina is perhaps a little too forgiving--The Eagle is nevertheless a light-hearted frolic whose balance of comedy and drama foreshadows later action films such as The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and The Mark of Zorro (1940). [80 min.]

Trivia buffs might note that although many history books often cite Wings (1927) as the first Best Picture recipient at the Academy Awards, the honor actually went to two films: William Wellman's Wings, for "production," and F.W. Murnau's Sunrise, for "unique and artistic production." If the latter category sounds more impressive than the former, that explains (in part at least) why Sunrise, and not Wings, remains one of the most revered films of all time. William Fox initially drew Murnau to America with the promise of a big budget and total creative freedom, and the fact that Murnau made the most of it with this stunning masterpiece ratified his peerless reputation as a cinematic genius.

Sunrise itself is deceptively simple. Subtitled somewhat enigmatically A Song of Two Humans, the film focuses on a country-dwelling married couple whose lives are disrupted by a temptress from the city. But Murnau draws waves of emotion by a bevy of groundbreaking filmmaking techniques. Most notable is the use of sound effects, pushing silent cinema one step closer to the talkie era--an achievement unfairly overshadowed by The Jazz Singer, released later in 1927. Murnau also creatively manipulates the use and effect of the cards (three years earlier, he had directed the title-free The Last Laugh).

The most striking aspect of Sunrise is its camera work. Working with a pair of cinematographers. Charles Rosher and Karl Strauss, Murnau borrowed from his own experience in the German Expressionist movement as well as from the pastoral portraits of the Dutch masters, particularly Jan Vermeer. Linked with graceful and inventive camera movements and accented with in-camera tricks (such as multiple exposures), each scene of Sunrise looks like a masterful still photograph.

As magical as the imagery may be, the very simplicity of the story lends Sunrise a formidable dramatic weight. George O'Brien, pondering the murder of his innocent wife Janet Gaynor, is wracked with guilt, and his wife responds with appropriate terror once his intentions become obvious. The boat trip leading to her intended demise is fraught with both suspense and an odd sense of sadness, as the good O'Brien struggles to bring his monstrous thoughts to their fruition. Margaret Livingston, as the urban seductress, in many ways seems like the feminine equivalent of Murnau's vampire Count Orlock (from the 1922 film Nosferatu), relentlessly preying on poor O'Brien's soul. In one scene he is even beset by spectral images of her, surrounding him, clutching at him, and provoking him with her murderous desires.

Alas, the film turned out to be a box-office flop, and Murnau died in a car accident a few years later. But Sunrise remains a benchmark by which all other films--silent or not--should be measured, a pinnacle of craft in a more primitive age whose sophistication belies the resources at the time. Its shadow looms over several subsequent great works, from Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) to Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast (1946,) yet at the same time its own brilliance is inimitable. [97 min.]

Sunrise itself is deceptively simple. Subtitled somewhat enigmatically A Song of Two Humans, the film focuses on a country-dwelling married couple whose lives are disrupted by a temptress from the city. But Murnau draws waves of emotion by a bevy of groundbreaking filmmaking techniques. Most notable is the use of sound effects, pushing silent cinema one step closer to the talkie era--an achievement unfairly overshadowed by The Jazz Singer, released later in 1927. Murnau also creatively manipulates the use and effect of the cards (three years earlier, he had directed the title-free The Last Laugh).

The most striking aspect of Sunrise is its camera work. Working with a pair of cinematographers. Charles Rosher and Karl Strauss, Murnau borrowed from his own experience in the German Expressionist movement as well as from the pastoral portraits of the Dutch masters, particularly Jan Vermeer. Linked with graceful and inventive camera movements and accented with in-camera tricks (such as multiple exposures), each scene of Sunrise looks like a masterful still photograph.

As magical as the imagery may be, the very simplicity of the story lends Sunrise a formidable dramatic weight. George O'Brien, pondering the murder of his innocent wife Janet Gaynor, is wracked with guilt, and his wife responds with appropriate terror once his intentions become obvious. The boat trip leading to her intended demise is fraught with both suspense and an odd sense of sadness, as the good O'Brien struggles to bring his monstrous thoughts to their fruition. Margaret Livingston, as the urban seductress, in many ways seems like the feminine equivalent of Murnau's vampire Count Orlock (from the 1922 film Nosferatu), relentlessly preying on poor O'Brien's soul. In one scene he is even beset by spectral images of her, surrounding him, clutching at him, and provoking him with her murderous desires.

Alas, the film turned out to be a box-office flop, and Murnau died in a car accident a few years later. But Sunrise remains a benchmark by which all other films--silent or not--should be measured, a pinnacle of craft in a more primitive age whose sophistication belies the resources at the time. Its shadow looms over several subsequent great works, from Orson Welles's Citizen Kane (1941) to Jean Cocteau's Beauty and the Beast (1946,) yet at the same time its own brilliance is inimitable. [97 min.]

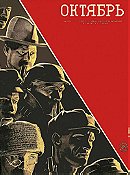

In 1926, Sergei M. Eisenstein went to Germany to present his new film The Battleship Potemkin. He left a promising young filmmaker, but he came back an international cultural superstar. A series of major film productions was being planned to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the Bolshevik victory. Eisenstein eagerly accepted the challenge of presenting on screen the revolutionary process in Russia--literally, how the country went from Aleksandr Kerensky's "Provisional Government," installed after the Czar's abdication, to the first victories of Lenin and his followers.

No expense was spared. Massive crowd scenes were organized, and city traffic was diverted so Eisenstein could shoot in the very sites where the depicted incident occurred. Contrary to popular belief, the film contains not one meter of documentary footage. Every shot was a re-creation. Working feverishly, Eisenstein finished just in time for the anniversary celebrations, but the reactions, official and otherwise, were less than enthusiastic. Many found the film confusing and difficult to follow. Others wondered why the role of Lenin was so greatly reduced (the actor playing him, Vasili Nikandrov, appears only a handful of times on screen.) Several critics who had supported Potemkin suggested that Eisenstein go back to the editing room and keep working.

There is no denying that October is some sort of masterpiece, but figuring out what kind is a real challenge. As a didactic tool, a means of "explaining" the revolution to the masses at home and abroad, the film is simply ineffective. For many audiences, sitting through it is a real chore. The characterizations are all paper thin, and anyone with even a smattering of historical knowledge can see right through its crude propaganda. Yet what is perhaps most powerful and touching about October is simply its level of ambition. Sergei M. Eisenstein was surely the cinema's most remarkable personality for the first 50 years of its existence, impossibly erudite, with an unlimited belief in cinema's potential. At his most delirious, Eisenstein imagined that cinema could represent "visual thinking"--not just arguments, but the process by which the mind constructs arguments. Photographic images, the raw material of cinema, had to be "neutralized" into sensations and stimuli so that a film could reveal concepts and not just people or things. The real engine that would drive the cinema machine as Eisenstein saw it was montage, editing: the "mystical" interaction that occurs when two separate pieces of film are joined together.

October is the purest, most cogent example of Eisenstein's theory and practice of cinema. There are several absolutely breathtaking sequences: the topping of the Czar's statue, the raising of the bridge, and especially the frequency cited "For God and Country" sequence. Evidence of the cold engineer that Eisenstein originally trained to be might be found in the cathedral-like intricacy of its editing. However, scratch just below the film's surface and you can feel the exhilaration--and the touch of madness--of an artist standing on the threshold of what he believes will be a brave new world. [95 min.]

No expense was spared. Massive crowd scenes were organized, and city traffic was diverted so Eisenstein could shoot in the very sites where the depicted incident occurred. Contrary to popular belief, the film contains not one meter of documentary footage. Every shot was a re-creation. Working feverishly, Eisenstein finished just in time for the anniversary celebrations, but the reactions, official and otherwise, were less than enthusiastic. Many found the film confusing and difficult to follow. Others wondered why the role of Lenin was so greatly reduced (the actor playing him, Vasili Nikandrov, appears only a handful of times on screen.) Several critics who had supported Potemkin suggested that Eisenstein go back to the editing room and keep working.

There is no denying that October is some sort of masterpiece, but figuring out what kind is a real challenge. As a didactic tool, a means of "explaining" the revolution to the masses at home and abroad, the film is simply ineffective. For many audiences, sitting through it is a real chore. The characterizations are all paper thin, and anyone with even a smattering of historical knowledge can see right through its crude propaganda. Yet what is perhaps most powerful and touching about October is simply its level of ambition. Sergei M. Eisenstein was surely the cinema's most remarkable personality for the first 50 years of its existence, impossibly erudite, with an unlimited belief in cinema's potential. At his most delirious, Eisenstein imagined that cinema could represent "visual thinking"--not just arguments, but the process by which the mind constructs arguments. Photographic images, the raw material of cinema, had to be "neutralized" into sensations and stimuli so that a film could reveal concepts and not just people or things. The real engine that would drive the cinema machine as Eisenstein saw it was montage, editing: the "mystical" interaction that occurs when two separate pieces of film are joined together.

October is the purest, most cogent example of Eisenstein's theory and practice of cinema. There are several absolutely breathtaking sequences: the topping of the Czar's statue, the raising of the bridge, and especially the frequency cited "For God and Country" sequence. Evidence of the cold engineer that Eisenstein originally trained to be might be found in the cathedral-like intricacy of its editing. However, scratch just below the film's surface and you can feel the exhilaration--and the touch of madness--of an artist standing on the threshold of what he believes will be a brave new world. [95 min.]

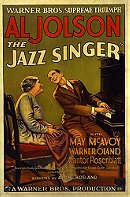

Throughout film history, certain movies have been the center of special attention, if not for their aesthetics, then for their role in the development of cinema as we know it. Alan Crosland's The Jazz Singer is undoubtedly one of the films that has marked the path of motion pictures as both an art form and a profitable industry. Released in 1927 by Warner Brothers and starring Al Jolson, one of the best-known vocal artists at the time, The Jazz Singer is unanimously considered the first feature-length sound movie. Although limited to musical performances and a few dialogues following and preceding such performances, the use of sound introduced innovative changes in the industry, destined to revolutionize Hollywood as hardly any other movie has done.

In its blend of vaudeville and melodrama, the plot is relatively simple. Jakie (Jolson) is the only teenage son of the devoted Cantor Rabinowitz (Warner Oland), who encourages his child to follow the same path of generations of Cantors in the family. Although profoundly influenced by his Jewish roots, Jakie's passion is jazz and he dreams about an audience inspired by his voice. After a family friend confesses to Cantor Rabinowitz to having seen Jakie singing in a cafe, the furious father punishes his son, causing him to run away from the family house and from his heartbroken mother Sara (Eugenie Besserer). Years later Jakie, aka Jack Robin, comes back as an affirmed jazz singer looking for reconciliation. Finding his father still harsh and now sick. Jack is forced to make a decision between his career as a blackface entertainer and his Jewish identity.

A milestone in film history representing a decisive step toward a new type of cinema and a new type of entertainment, The Jazz Singer is more than just the first "talkie." As Michael Rogin, the famed political scientist, has argued, The Jazz Singer can be cited as a typical example of Jewish transformation in U.S. society: the racial assimilation into white America, the religious conversion to less strict spiritual dogma, and the entrepreneurial integration into the American motion picture industry during the time of the coming of sound. [88 min.]

In its blend of vaudeville and melodrama, the plot is relatively simple. Jakie (Jolson) is the only teenage son of the devoted Cantor Rabinowitz (Warner Oland), who encourages his child to follow the same path of generations of Cantors in the family. Although profoundly influenced by his Jewish roots, Jakie's passion is jazz and he dreams about an audience inspired by his voice. After a family friend confesses to Cantor Rabinowitz to having seen Jakie singing in a cafe, the furious father punishes his son, causing him to run away from the family house and from his heartbroken mother Sara (Eugenie Besserer). Years later Jakie, aka Jack Robin, comes back as an affirmed jazz singer looking for reconciliation. Finding his father still harsh and now sick. Jack is forced to make a decision between his career as a blackface entertainer and his Jewish identity.

A milestone in film history representing a decisive step toward a new type of cinema and a new type of entertainment, The Jazz Singer is more than just the first "talkie." As Michael Rogin, the famed political scientist, has argued, The Jazz Singer can be cited as a typical example of Jewish transformation in U.S. society: the racial assimilation into white America, the religious conversion to less strict spiritual dogma, and the entrepreneurial integration into the American motion picture industry during the time of the coming of sound. [88 min.]

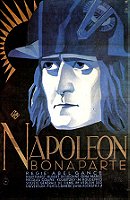

Napoleon (1927) (1927)

At 333 minutes in its longest extant version, Abel Gance's 1927 biopic is an epic on a scale to satisfy its subject. Although it follows from his schooldays in 1780--marshalling snowball fights--through to his triumphant Italian campaign of 1796, by contemporary standards the film lacks depth. For Gance, Napoleon (played by the appropriately named Albert Dieudonne) was a "man of destiny," not psychology. His paean to the French Emperor has something in common with Sergei Eisenstein's Alexander Nevsky (1938), both thrilling pieces of cinema in the service of nationalist propaganda.

If Gance is more of an innovator than an artist, it's a measure of his brilliance that Napoleon still brims with energy and invention today. None of his contemporaries--not even Murnau--used the camera with such inspiration. Gance thought nothing of strapping cameramen to hoses; he even mounted a camera on the guillotine. In one brilliant sequence, he captures the revolutionary spirit of a rousing (silent) rendition of "La Marseilles" by swinging the camera above the set as if it were on a trapeze. His most spectacular coup, though, is "Polyvision," a split-screen effect which called for three projectors to create a triptych--nearly three decades before the advent of Cinerama. [378 min.]

If Gance is more of an innovator than an artist, it's a measure of his brilliance that Napoleon still brims with energy and invention today. None of his contemporaries--not even Murnau--used the camera with such inspiration. Gance thought nothing of strapping cameramen to hoses; he even mounted a camera on the guillotine. In one brilliant sequence, he captures the revolutionary spirit of a rousing (silent) rendition of "La Marseilles" by swinging the camera above the set as if it were on a trapeze. His most spectacular coup, though, is "Polyvision," a split-screen effect which called for three projectors to create a triptych--nearly three decades before the advent of Cinerama. [378 min.]

The Kid Brother (1927)

Harold Lloyd is often regarded as the "third genius" of silent American comedy, his 1920s' work often considerably more successful with the public than that of Buster Keaton, and even Charlie Chaplin. Often directly associated with the Zeitgeist of the Jazz Age, Lloyd's screen persona is routinely noted for its "speedy," can-do optimism and his films singled out for the audacious, often dangerous stunts and acrobatic feats that they contain. In many of his films the wonders of modernity and their embodiment in the teeming city itself are chief preoccupations. The Kid Brother, Lloyd's second feature for Paramount, is often considered to be the bespectacled comic's best and most holistic film. In many ways it deliberately turns its back on the 1920s, returning somewhat to the rural "idyll" of the 1922 film Grandma's Boy.

The film's two most startling sequences provide a kind of essay in contrast, illustrating the combination of both a delicate and somewhat more rugged athleticism that marks Lloyd's best work. In the first sequence, Lloyd is shown climbing a tall tree to attain a slightly longer look at the woman he has just met (and fallen for). This sequence illustrates the often meticulous and technically adventurous aspects of Lloyd's cinema--an elevator was built to accommodate the ascending camera--and the ways these are intricately connected to elements of character and situation (also demonstrating Lloyd's masterly use of props). The second extended sequence features a fight between Lloyd and his chief antagonist, and is remarkable for its sustained ferocity and precise staging. Both sequences show Lloyd's character transcending his seeming limitations, moving beyond appearance, and traveling that common trajectory from mama's boy to triumphant "average" American. [84 min.]

The film's two most startling sequences provide a kind of essay in contrast, illustrating the combination of both a delicate and somewhat more rugged athleticism that marks Lloyd's best work. In the first sequence, Lloyd is shown climbing a tall tree to attain a slightly longer look at the woman he has just met (and fallen for). This sequence illustrates the often meticulous and technically adventurous aspects of Lloyd's cinema--an elevator was built to accommodate the ascending camera--and the ways these are intricately connected to elements of character and situation (also demonstrating Lloyd's masterly use of props). The second extended sequence features a fight between Lloyd and his chief antagonist, and is remarkable for its sustained ferocity and precise staging. Both sequences show Lloyd's character transcending his seeming limitations, moving beyond appearance, and traveling that common trajectory from mama's boy to triumphant "average" American. [84 min.]

Storm Over Asia (1928)

Within a month of completing 1927: The End of St. Petersburg, Vsevolod Pudovkin was at work on this epic fable, apparently inspired both by I. Novokshonov's original story of a herdsman who will rise to become a great leader, and by the prospect of shooting in virgin territory, exotic Outer Mongolia. Pudovkin's State Film School classmate Valeri Inkizhinov plays the unnamed hero, a Mongol who learns to distrust capitalists when a Western fur trader cheats him out of a rare silver fox pelt. The year is 1918, and the Mongol falls in with Socialist partisans fighting against the imperialist British occupying army. Captured, he is condemned to be shot (for recognizing the word "Moscow"), but his life is saved when an ancient talisman is found on his person, a document that proclaims the bearer to be a direct descendant of Genghis Khan. The British install him as a puppet king, but he escapes to lead his people to a fantastic victory.

A curious mix of rip-roaring adventure filmmaking, Soviet socialist propaganda, and ethnographic documentary, Storm over Asia is never less than entertaining. It is distinguished by Pudovkin's epic compositional sense, evident in the cavalry column fanning out to fill the horizon, and some striking cubist-like montage sequences--as well as for its sardonic satire of Buddhist ritual and Western betrayal of faith. [93 min.]

A curious mix of rip-roaring adventure filmmaking, Soviet socialist propaganda, and ethnographic documentary, Storm over Asia is never less than entertaining. It is distinguished by Pudovkin's epic compositional sense, evident in the cavalry column fanning out to fill the horizon, and some striking cubist-like montage sequences--as well as for its sardonic satire of Buddhist ritual and Western betrayal of faith. [93 min.]

A Throw of Dice (1930)

A German production in collaboration with the actor-producer Himansu Rai, filmed entirely on location in India and based on an episode from the Mahabharata, A Throw of Dice, is a magnificent and alluring epic. Osten's most critically acclaimed film, it was his third collaboration with Rai, after The Light of Asia (1925), about the life of Buddha, and Shiraz (1928), which dramatizes events around the building of the Taj Mahal.

Two kings vie for the hand of young Sunita (Seeta Devi). She is enamored of Ranjit (Charu Roy), who is no less besotted with her. Sohan (Himansu Rai) sees her as a way to gain more power. Knowing Ranjit to be addicted to gambling, Sohan uses a set of loaded dice to win Sunita's hand and, eventually, his rival's kingdom. Only when Sunita discovers the dice is Ranjit able to muster the forces to overthrow Sohan.

One of A Throw of Dice's most striking elements is the naturalism of the performances, particularly compared with the declamatory style of much Western acting at that time. Also noteworthy are Osten and cinematographer Emil Schuemann's stunning visuals, which capture the beauty of India's landscape and its grand palaces along the Ganges.

The film was restored in time for the sixtieth anniversary of India's independence. Featuring an atmospheric score by Nitin Sawhney, accentuating the unbridled romanticism of Osten's drama, it now ranks as one of the pinnacles of early cinema. [74 min.]

Two kings vie for the hand of young Sunita (Seeta Devi). She is enamored of Ranjit (Charu Roy), who is no less besotted with her. Sohan (Himansu Rai) sees her as a way to gain more power. Knowing Ranjit to be addicted to gambling, Sohan uses a set of loaded dice to win Sunita's hand and, eventually, his rival's kingdom. Only when Sunita discovers the dice is Ranjit able to muster the forces to overthrow Sohan.

One of A Throw of Dice's most striking elements is the naturalism of the performances, particularly compared with the declamatory style of much Western acting at that time. Also noteworthy are Osten and cinematographer Emil Schuemann's stunning visuals, which capture the beauty of India's landscape and its grand palaces along the Ganges.

The film was restored in time for the sixtieth anniversary of India's independence. Featuring an atmospheric score by Nitin Sawhney, accentuating the unbridled romanticism of Osten's drama, it now ranks as one of the pinnacles of early cinema. [74 min.]

A lasting masterpiece from G.W. Pabst, adapted from Frank Wedekind's "Lulu" plays, Pandora's Box is remembered for the creation of the archetypal character in Lulu (Louise Brooks), an innocent temptress whose forthright sexuality somehow winds up ruining the lives of everyone around her. Though Pabst was criticized at the time for casting a foreigner in a role that was considered emblematically German, the main reason the film is remembered is the performance of American star Brooks. So powerful and sexual a presence that she never managed to make a transition from silent flapper parts to the talkie roles she deserved in a Hollywood dominated by Shirley Temple, Brooks is the definitive gamine vamp, modeling a sharp-banged bobbed haircut known as a "Louise Brooks" or "Lulu" to this day.

Presented in distinct theatrical "acts," the story picks up Lulu in a bourgeois Berlin drawing room, where she is the adored mistress of widowed newspaper publisher Peter Schon (Fritz Kortner), friendly with her lover's grown-up son Alwa (Franz Lederer) and even with the gnomish pimp Schigolch (Carl Goetz), who is either her father or her first lover. When Schon announces that he is remarrying, Lulu seems to be passed on to a nightclub strongman (Kraft-Raschig) but, provoked when Schon tells his son that "one does not marry" a woman like her, sets up an incident backstage at the music hall where she is dancing that breaks off the editor's engagement and prompts her lover to marry her, though he knows that it will be the death of him.

Though her husband in effect commits suicide, Lulu ends up convicted of his murder. On the run with Alwa, Schigolch, and her lesbian admirer Countess Geschwitz (Alice Roberts), she makes it to an opium-hazed gambling boat on the Seine--where she is almost sold to an Egyptian brothel and Alwa is humiliatingly caught cheating--then finally to a Christmassy London, where she is stalked by Jack the Ripper (Gustav Diessl). Pabst surrounds Brooks with startling secondary characters and dizzying settings (the spectacle in the thronged wings of the cabaret eclipses anything taking place on stage), but it is the actress's vibrant erotic, scary, and heartbreaking personality that resonates with modern audiences. Brooks's mix of image and attitude is so strong and fresh that she makes Madonna like like Phyllis Diller, and her acting style is strikingly unmannered for the silent era, unmediated by the trickery of mime or expressionist makeup. Her performance is also remarkably honest: never playing for easy sentiment, the audience is forced to recognize how destructive Lulu is even as we fall under her spell.

The original plays are set in 1888, the year of the Ripper murders, yet Pabst imagines a fantastical but contemporary setting, which seems to begin with the 1920s modernity of Berlin and then travels back in time to a foggy London for a death scene that is the cinema's first great insight into the mindset of a serial killer. Lulu, turned streetwalker so that Schigolch can afford a last Christmas pudding, charms the reticent Jack, who throws aside his knife and genuinely tries not to kill again but is ultimately overwhelmed by the urge to stab. [97 min.]

Presented in distinct theatrical "acts," the story picks up Lulu in a bourgeois Berlin drawing room, where she is the adored mistress of widowed newspaper publisher Peter Schon (Fritz Kortner), friendly with her lover's grown-up son Alwa (Franz Lederer) and even with the gnomish pimp Schigolch (Carl Goetz), who is either her father or her first lover. When Schon announces that he is remarrying, Lulu seems to be passed on to a nightclub strongman (Kraft-Raschig) but, provoked when Schon tells his son that "one does not marry" a woman like her, sets up an incident backstage at the music hall where she is dancing that breaks off the editor's engagement and prompts her lover to marry her, though he knows that it will be the death of him.

Though her husband in effect commits suicide, Lulu ends up convicted of his murder. On the run with Alwa, Schigolch, and her lesbian admirer Countess Geschwitz (Alice Roberts), she makes it to an opium-hazed gambling boat on the Seine--where she is almost sold to an Egyptian brothel and Alwa is humiliatingly caught cheating--then finally to a Christmassy London, where she is stalked by Jack the Ripper (Gustav Diessl). Pabst surrounds Brooks with startling secondary characters and dizzying settings (the spectacle in the thronged wings of the cabaret eclipses anything taking place on stage), but it is the actress's vibrant erotic, scary, and heartbreaking personality that resonates with modern audiences. Brooks's mix of image and attitude is so strong and fresh that she makes Madonna like like Phyllis Diller, and her acting style is strikingly unmannered for the silent era, unmediated by the trickery of mime or expressionist makeup. Her performance is also remarkably honest: never playing for easy sentiment, the audience is forced to recognize how destructive Lulu is even as we fall under her spell.

The original plays are set in 1888, the year of the Ripper murders, yet Pabst imagines a fantastical but contemporary setting, which seems to begin with the 1920s modernity of Berlin and then travels back in time to a foggy London for a death scene that is the cinema's first great insight into the mindset of a serial killer. Lulu, turned streetwalker so that Schigolch can afford a last Christmas pudding, charms the reticent Jack, who throws aside his knife and genuinely tries not to kill again but is ultimately overwhelmed by the urge to stab. [97 min.]

Genre can be used to read history and interpret moments in time. Accordingly, Mervyn LeRoy's Little Caesar helped to define the gangster movie while serving as an allegory of production circumstances because it was produced during the Great Depression. Within the film is inscribed a wholesale paranoia about individual achievement in the face of economic devastation. Leavening this theme alongside the demands of social conformity during the early 1930s means that LeRoy's screen classic is far more than the simple sum of its parts.

Caesar "Rico" Bandello (Edward G. Robinson) is a small-stakes thief with a partner named Joe (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) Recognizing a dead-end future, they move to the heart of Chicago, where Joe becomes an entertainer and falls in love with a dancer named Olga (Glenda Farrell). In contrast, Rico gets a taste of the "life" and enjoys it. Possessing a psychotic ruthlessness, he gradually looms as the new power on-scene before finally succumbing to an ill-tempered ego and the syndicate-breaking police. Gun shot and dying beneath an ad for Joe and Olga's dinner act, Rico sputters some final words of self-determination, underlining how he won't ever be caught because he lived according to the terms of his own ambition.

For audiences, Rico's killer was undoubtedly a clear call of recent tension about the state of the world at the time. Limited by the feature film's structure, but not dulled by censorial practice in the days before the Production Code Administration, Little Caesar offers a scornful look at free enterprises taken to an extreme. Seen through the long view of history and the focus of ill-gotten gain, it's a perfect corollary for Wall Street's collapse, itself the result of poor regulation, mass speculation, and hysteria manipulated to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

Acting out to get a bigger piece of the pie, Rico expresses the wish for acceptance and the drive toward success in an otherwise indifferent world. Simultaneously terrorizing innocents and devastating the society he desires to control, he ends up illuminating the demands of power with homicidal shadows in this, a seminal film of the early sound era. [79 min.]

Caesar "Rico" Bandello (Edward G. Robinson) is a small-stakes thief with a partner named Joe (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) Recognizing a dead-end future, they move to the heart of Chicago, where Joe becomes an entertainer and falls in love with a dancer named Olga (Glenda Farrell). In contrast, Rico gets a taste of the "life" and enjoys it. Possessing a psychotic ruthlessness, he gradually looms as the new power on-scene before finally succumbing to an ill-tempered ego and the syndicate-breaking police. Gun shot and dying beneath an ad for Joe and Olga's dinner act, Rico sputters some final words of self-determination, underlining how he won't ever be caught because he lived according to the terms of his own ambition.

For audiences, Rico's killer was undoubtedly a clear call of recent tension about the state of the world at the time. Limited by the feature film's structure, but not dulled by censorial practice in the days before the Production Code Administration, Little Caesar offers a scornful look at free enterprises taken to an extreme. Seen through the long view of history and the focus of ill-gotten gain, it's a perfect corollary for Wall Street's collapse, itself the result of poor regulation, mass speculation, and hysteria manipulated to benefit the few at the expense of the many.

Acting out to get a bigger piece of the pie, Rico expresses the wish for acceptance and the drive toward success in an otherwise indifferent world. Simultaneously terrorizing innocents and devastating the society he desires to control, he ends up illuminating the demands of power with homicidal shadows in this, a seminal film of the early sound era. [79 min.]

Two conmen, Louis (Raymond Cordy) and Emile (Henri Merchand), plan their escape from prison. Upon breaking out, Emile is recaptured but Louis runs free and builds an empire on the assembly-line principle. Eventually Emile is paroled and heads to Louis's factory. Within its walls he becomes smitten with a secretary named Jeanne (Rolla France) and asks his old friend for help. According to the rules of comeuppance, Louis is then threatened with discovery as an escaped felon, after which the two men earn lasting freedom as hobos on the road.

Unlike Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times, a film later sued for plagerism by Tobis, the production company of A Nous la Liberte, Rene Clair's film is an exaltation of industrial society. Opening on an assembly line and closing in a mechanized factory, the fears often associated with modernization are wholly absent here. Instead these are substituted with values of loyalty and the comedy of circumstance.

Interestingly, much of the humor in A Nous la Liberte stems from carefully manipulated screen space and sequence. First the assembly line hiccups. Then a worker forgets his place, disrupts another worker, angers his boss, and so on. It's a formula freed from dialogue and adopted directly from the silent cinema as a transitional vehicle into the talkies. [104 min.]

Unlike Charlie Chaplin's Modern Times, a film later sued for plagerism by Tobis, the production company of A Nous la Liberte, Rene Clair's film is an exaltation of industrial society. Opening on an assembly line and closing in a mechanized factory, the fears often associated with modernization are wholly absent here. Instead these are substituted with values of loyalty and the comedy of circumstance.

Interestingly, much of the humor in A Nous la Liberte stems from carefully manipulated screen space and sequence. First the assembly line hiccups. Then a worker forgets his place, disrupts another worker, angers his boss, and so on. It's a formula freed from dialogue and adopted directly from the silent cinema as a transitional vehicle into the talkies. [104 min.]

David Bowie chose it as one of his favorite films. Orson Welles watched it in the 1940s. And it was screened for Marie Falconetti, Carl Theodor Dreyer's Joan of Arc. Limite is a cult film, but how and why?

The conventional wisdom is that Brazilian cinema started in the 1950s. But two decades earlier, in 1930, aged just twenty-one, Mario Peixoto made this extraordinary film. A man and a woman are handcuffed together--shades of Alfred Hitchcock. But where Hitch would race such a couple through a thriller story, Peixoto, woozy with the influence of the French Avant-Garde, makes something more dreamlike.

The whole film seems to drift, languorously. Special camera mounts were made so that ropes could haul the image into the air to make it soar. Peixoto talked about the "camera-brain," and it's hard not to connect some of his visual ideas to the literary ideas of Virginia Woolf or the movies of French impressionist Germaine Dulac. Past mixes with present. The people, whose clothes are ragged and who seem immensely sad, remember recent events. Story is downplayed, but feeling, perception, looking, and subjectivity animate this film. Limite was restored by Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Foundation and, when the restoration was shown in Cannes, its slow rhythms seemed like an elegy, or Derek Jarman's The Angelic Conversation (1987). [114 min.]

The conventional wisdom is that Brazilian cinema started in the 1950s. But two decades earlier, in 1930, aged just twenty-one, Mario Peixoto made this extraordinary film. A man and a woman are handcuffed together--shades of Alfred Hitchcock. But where Hitch would race such a couple through a thriller story, Peixoto, woozy with the influence of the French Avant-Garde, makes something more dreamlike.

The whole film seems to drift, languorously. Special camera mounts were made so that ropes could haul the image into the air to make it soar. Peixoto talked about the "camera-brain," and it's hard not to connect some of his visual ideas to the literary ideas of Virginia Woolf or the movies of French impressionist Germaine Dulac. Past mixes with present. The people, whose clothes are ragged and who seem immensely sad, remember recent events. Story is downplayed, but feeling, perception, looking, and subjectivity animate this film. Limite was restored by Martin Scorsese's World Cinema Foundation and, when the restoration was shown in Cannes, its slow rhythms seemed like an elegy, or Derek Jarman's The Angelic Conversation (1987). [114 min.]

Rene Clair's The Million opens on a Parisian rooftoop. Two lovers flirt and retire to their respective apartments, after which the camera dollies along the skyline in a one-shot sequence using forced perspective, miniatures, and matte paintings. Such a tricky sequence demonstrates a profoundly advanced cinematic style while also revealing how Clair's film is no throwaway musical comedy.

A poor artist named Michel (Rene Lefevre) owes money to various creditors. Engaged to the pure-hearted Beatrice (Annabella), he disregards her to chase after the floozy Wanda (Vanda Greville) and otherwise keeps up with his friend Prosper (Louis Allibert). When the gangster Grandpa Tulip (Paul Ollivier) races into the apartment building to avoid the police, Beatrice gives him an old jacket of Michel's out of spite. Afterwards, Michel and Prosper realize that a lottery ticket they purchased is a millionaire's prize--but the ticket is in the jacket Beatrice gave Grandpa Tulip, who in turn pawned it to the tenor Sopranelli (Constantin Siroesco), who will soon travel to America. Thus the caper comedy of The Million is set in motion. Mix-ups, misidentifacation, disguises, upsets, reconciliation, and musical numbers follow, all of it to bring Michel and Beatrice together and restore the lottery ticket to its rightful owner. Along the way a thug in tuxedo tails cries for a love song, a race for the jacket is scored to the sounds of a rugby match, and the opportunistic demands of Michel's creditors and neighbors weigh in on his perceived riches.

Perhaps most remarkable among its virtues is the film's integration of synch-sound recording. Expository dialogue is offered to still camera setups whereas lesser remarks, often viewed as whispers between characters, are left in silence. To cover these gaps in the spoken record, ambient music stitches together each set piece with occasional bursts of song. More fluid and visually dynamic than many early sound films, The Million is also more entertaining than many subsequent talkies. In large part this is a credit to Clair's screenplay and deft direction, but is is also due to a willing cast carrying through the demands of a gentle fantasy. [89 min.]

A poor artist named Michel (Rene Lefevre) owes money to various creditors. Engaged to the pure-hearted Beatrice (Annabella), he disregards her to chase after the floozy Wanda (Vanda Greville) and otherwise keeps up with his friend Prosper (Louis Allibert). When the gangster Grandpa Tulip (Paul Ollivier) races into the apartment building to avoid the police, Beatrice gives him an old jacket of Michel's out of spite. Afterwards, Michel and Prosper realize that a lottery ticket they purchased is a millionaire's prize--but the ticket is in the jacket Beatrice gave Grandpa Tulip, who in turn pawned it to the tenor Sopranelli (Constantin Siroesco), who will soon travel to America. Thus the caper comedy of The Million is set in motion. Mix-ups, misidentifacation, disguises, upsets, reconciliation, and musical numbers follow, all of it to bring Michel and Beatrice together and restore the lottery ticket to its rightful owner. Along the way a thug in tuxedo tails cries for a love song, a race for the jacket is scored to the sounds of a rugby match, and the opportunistic demands of Michel's creditors and neighbors weigh in on his perceived riches.