Movies Roger Ebert Didn't Like That Others Did

Sort by:

Showing 23 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

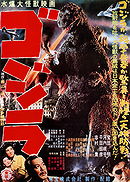

Godzilla (1954)

Roger Ebert's comment:

"Regaled for 50 years by the stupendous idiocy of the American version of "Godzilla," audiences can now see the original Japanese version, which is equally idiotic, but, properly decoded, was the "Fahrenheit 9/11" of its time. Both films come after fearsome attacks on their nations, embody urgent warnings, and even incorporate similar dialogue, such as "The report is of such dire importance it must not be made public." Is that from 1954 Tokyo or 2004 Washington?

The first "Godzilla" set box office records in Japan and inspired countless sequels, remakes and rip-offs. It was made shortly after an American H-bomb test in the Pacific contaminated a large area of ocean and gave radiation sickness to a boatload of Japanese fishermen. It refers repeatedly to Nagasaki, H-bombs and civilian casualties, and obviously embodies Japanese fears about American nuclear tests.

But that is not the movie you have seen. For one thing, it doesn't star Raymond Burr as Steve Martin, intrepid American journalist, who helpfully explains, "I was headed for an assignment in Cairo when I dropped off for a social call in Tokyo."

In the '50s, the American producer Joseph E. Levine bought the Japanese film, cut it by 40 minutes, removed all of the political content, and awkwardly inserted Burr into scenes where he clearly did not fit. The hapless actor gives us reaction shots where he's looking in the wrong direction, listens to Japanese actors dubbed into the American idiom (they always call him, "Steve Martin" or even "the famous Steve Martin"), and provides a reassuring conclusion in which Godzilla is seen as some kind of public health problem, or maybe just a malcontent.

The Japanese version, now in general U.S. release to mark the film's 50th anniversary, is a bad film, but with an undeniable urgency. I learn from helpful notes by Mike Flores of the Psychotronic Film Society that the opening scenes, showing fishing boats disappearing as the sea boils up, would have been read by Japanese audiences as a coded version of U.S. underwater H-bomb tests. Much is made of a scientist named Dr. Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), who could destroy Godzilla with his secret weapon, the Oxygen Destroyer, but hesitates because he is afraid the weapon might fall into the wrong hands, just as H-bombs might, and have. The film's ending warns that atomic tests may lead to more Godzillas. All cut from the U.S. version.

In these days of flawless special effects, Godzilla and the city he destroys are equally crude. Godzilla at times looks uncannily like a man in a lizard suit, stomping on cardboard sets, as indeed he was, and did. Other scenes show him as a stuffed, awkward animatronic model. This was not state of the art even at the time; "King Kong" (1933) was much more convincing.

When Dr. Serizawa demonstrates the Oxygen Destroyer to the fiancee of his son, the superweapon is somewhat anticlimactic. He drops a pill into a tank of tropical fish, the tank lights up, he shouts "stand back!," the fiancee screams, and the fish go belly up. Yeah, that'll stop Godzilla in his tracks.

Reporters covering Godzilla's advance are rarely seen in the same shot with the monster. Instead, they look offscreen with horror; a TV reporter, broadcasting for some reason from his station's tower, sees Godzilla looming nearby and signs off, "Sayonara, everyone!" Meanwhile, searchlights sweep the sky, in case Godzilla learns to fly.

The movie's original Japanese dialogue, subtitled, is as harebrained as Burr's dubbed lines. When the Japanese Parliament meets (in what looks like a high school home room), the dialogue is portentous but circular:

"The professor raises an interesting question! We need scientific research!"

"Yes, but at what cost?"

"Yes, that's the question!"

Is there a reason to see the original "Godzilla"? Not because of its artistic stature, but perhaps because of the feeling we can sense in its parable about the monstrous threats unleashed by the atomic age. There are shots of Godzilla's victims in hospitals, and they reminded me of documentaries of Japanese A-bomb victims. The incompetence of scientists, politicians and the military will ring a bell.

This is a bad movie, but it has earned its place in history, and the enduring popularity of Godzilla and other monsters shows that it struck a chord. Can it be a coincidence, in these years of trauma after 9/11, that in a 2005 remake, King Kong will march once again on New York?"

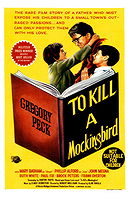

To Kill a Mockingbird (1962)

""To Kill a Mockingbird" is a time capsule, preserving hopes and sentiments from a kinder, gentler, more naive America. It was released in December 1962, the last month of the last year of the complacency of the postwar years. The following November, John F. Kennedy would be assassinated. Nothing would ever be the same again -- not after the deaths of Martin Luther King, Robert Kennedy, Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, not after the war in Vietnam, certainly not after September 11, 2001. The most hopeful development during that period for America was the civil rights movement, which dealt a series of legal and moral blows to racism. But "To Kill a Mockingbird," set in Maycomb, Alabama, in 1932, uses the realities of its time only as a backdrop for the portrait of a brave white liberal.

The movie has remained the favorite of many people. It is currently listed as the 29th best film of all time in a poll by the Internet Movie Database. Such polls are of questionable significance, but certainly the movie and the Harper Lee novel on which it is based have legions of admirers. It is being read by many Chicagoans as part of a city-wide initiative in book discussion. It is a beautifully-written book, but it should be used not as a record of how things are, or were, but of how we once liked to think of them.

The novel, which focuses on the coming of age of three young children, especially the tomboy Scout, gains strength from her point of view: It sees the good and evil of the world through the eyes of a six-year-old child. The movie shifts the emphasis to the character of her father, Atticus Finch, but from this new point of view doesn't see as much as an adult in that time and place should see.

Maycomb is evoked by director Robert Mulligan as a "tired old town" of dirt roads, picket fences, climbing vines, front porches held up by pillars of brick, rocking chairs, and Panama hats. Scout (Mary Badham) and her 10-year-old brother Jem (Philip Alford) live with their widowed father Atticus Finch (Gregory Peck) and their black housekeeper Calpurnia (Estelle Evans). They make friends with a new neighbor named "Dill" Harris (John Megna), who wears glasses, speaks with an expanded vocabulary, is small for his age, and is said to be inspired by Harper Lee's childhood friend Truman Capote. Atticus goes off every morning to his law office downtown, and the children play through lazy hot days.

Their imagination is much occupied by the Radley house, right down the street, which seems always dark, shaded and closed. Jem tells Dill that Mr. Radley keeps his son Boo chained to a bed in the house, and describes Boo breathlessly: "Judging from his tracks, he's about six and a half feet tall. He eats raw squirrels and all the cats he can catch. There's a long, jagged scar that runs all the way across his face. His teeth are yellow and rotten. His eyes are popped. And he drools most of the time." Of course the first detail reveals Jem has never seen Boo.

Into this peaceful calm drops a thunderbolt. Atticus is asked by the town judge to defend a black man named Tom Robinson (Brock Peters), who has been accused of raping a poor white girl named Mayella Violet Ewell (Collin Wilcox). White opinion is of course much against the black man, who is presumed guilty, and Mayelle's father Bob (James Anderson) pays an ominous call on Atticus, indirectly threatening his children. The children are also taunted at school, and get in fights; Atticus explains to them why he is defending a Negro, and warns them against using the word "nigger."

The courtroom scenes are the most celebrated in the movie; they make it perfectly clear that Tom Robinson is innocent, that no rape occurred, that Maybelle came on to Robinson, that he tried to flee, that Bob Ewell beat his own daughter, and she lied about it out of shame for feeling attracted to a black man. Atticus' summation to the jury is one of Gregory Peck's great scenes, but of course the all-white jury finds Tom Robinson guilty anyway. The verdict is greeted by an uncanny quiet: No whoops of triumph from Bob Ewell, no cries of protests by the blacks in the courtroom gallery. The whites file out quickly, but the blacks remain and stand silently in honor of Atticus as he walks out a little later. Scout and her brother sat up with the blacks throughout the trial, and now a minister tells her: "Miss Jean Louise, stand up, your father's passin'."

The problem here, for me, is that the conviction of Tom Robinson is not the point of the scene, which looks right past him to focus on the nobility of Atticus Finch. I also wonder at the general lack of emotion in the courtroom, and the movie only grows more puzzling by what happens next. Atticus is told by the sheriff that while Tom Robinson was being taken for safekeeping to nearby Abbottsville, he broke loose and tried to run away. As Atticus repeats the story: "The deputy called out to him to stop. Tom didn't stop. He shot at him to wound him and missed his aim. Killed him. The deputy says Tom just ran like a crazy man."

That Scout could believe it happened just like this is credible. That Atticus Finch, an adult liberal resident of the Deep South in 1932, has no questions about this version is incredible. In 1962 it is possible that some (white) audiences would believe that Tom Robinson was accidentally killed while trying to escape, but in 2001 such stories are met with a weary cynicism.

The construction of the following scene is highly implausible. Atticus drives out to Tom Robinson's house to break the sad news to his widow, Helen. She is played by Kim Hamilton (who is not credited, and indeed has no speaking lines in a film that finds time for dialog by two superfluous white neighbors of the Finches). On the porch are several male friends and relatives. Bob Ewell, the vile father who beat his girl into lying, lurches out of the shadows and says to one of them, "Boy, go in the house and bring out Atticus Finch." One of the men does so, Ewell spits in Atticus's face, Atticus stares him down and drives away. The black people in this scene are not treated as characters, but as props, and kept entirely in long shot. The close-ups are reserved for the white hero and villain.

It may be that in 1932 the situation was such in Alabama that this white man, who the people on that porch had seen lie to convict Tom Robinson, could walk up to them alone after they had just learned he had been killed, call one of them "boy," and not be touched. If black fear of whites was that deep in those days, then the rest of the movie exists in a dream world.

The upbeat payoff involves Ewell's cowardly attack on Scout and Jem, and the sudden appearance of the mysterious Boo Radley (Robert Duvall, in his first screen performance), to save them. Ewell is found dead with a knife under his ribs. Boo materializes inside the Finch house, is identified by Scout as her savior, and they're soon sitting side by side on the front porch swing. The sheriff decides that no good would be served by accusing Boo of the death of Ewell. That would be like "killing a mockingbird," and we know from earlier in the film that you can shoot all the bluejays you want, but not mockingbirds -- because all they do is sing to bring music to the garden. Not exactly a description of the silent Boo Radley, but we get the point.

This is a tricky note to end on, because it brings Boo Radley in literally from the wings as a distraction from the facts: An innocent black man was framed for a crime that never took place, he was convicted by a white jury in the face of overwhelming evidence, and he was shot dead in problematic circumstances. Now we are expected to feel good because the events got Boo out of the house. That Boo Radley killed Bob Ewell may be justice, but it is not parity. The sheriff says, "There's a black man dead for no reason, and now the man responsible for it is dead. Let the dead bury the dead this time." But I doubt that either Tom Robinson or Bob Ewell would want to be buried by the other.

"To Kill a Mockingbird" is, as I said, a time capsule. It expresses the liberal pieties of a more innocent time, the early 1960s, and it goes very easy on the realities of small-town Alabama in the 1930s. One of the most dramatic scenes shows a lynch mob facing Atticus, who is all by himself on the jailhouse steps the night before Tom Robinson's trial. The mob is armed and prepared to break in and hang Robinson, but Scout bursts onto the scene, recognizes a poor farmer who has been befriended by her father, and shames him (and all the other men) into leaving. Her speech is a calculated strategic exercise, masked as the innocent words of a child; one shot of her eyes shows she realizes exactly what she's doing. Could a child turn away a lynch mob at that time, in that place? Isn't it nice to think so."

filmbuilder's rating:

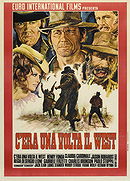

Once Upon a Time in the West (1968)

"Sergio Leone's "Once Upon a Time in the West" is a painstaking distillation of the style he made famous in the original three Clint Eastwood Westerns. There's the same eerie music; the same sweaty, ugly faces; the same rhythm of waiting and violence; the same attention to small details of Western life.

There is also, unfortunately, Leone's inability to call it quits. The movie stretches on for nearly three hours, with intermission, and provides two false alarms before it finally ends. In between, we're given a plot complex enough for Antonioni, involving killers, land rights, railroads, long-delayed revenge, mistaken identity, love triangles, double-crosses and shoot-outs. We're well into the second hour of the movie before the plot becomes quite clear.

These difficulties notwithstanding, "Once Upon a Time in the West" is good fun, especially if you like Leone's way of savoring the last morsel of every scene. A final shoot-out between Henry Fonda and Charles Bronson, for example, takes at least 15 minutes. They walk. They wait. They circle each other. They stare at each other. They squint. They spit. They take off their jackets. They wince. Just when they finally seem prepared to shoot after all, Leone uses a flashback. But why hurry a good shoot-out?

Leone's first two "spaghetti Westerns" ("A Fistful of Dollars," "For a Few Dollars More") were made with small budgets. His third, "The Good, the Bad and the Ugly," was made with a few dollars more. But this one was bankrolled by Paramount and looks like it: There's a wealth of detail, a lot of extras, elaborate sets. There's a sense of the life of the West going on all around the action (and that sense is impossible to obtain on small budgets).

Leone produces some interesting performances by casting against type. Henry Fonda is the bad guy for once in his career; Charles Bronson is impressively inscrutable as the mysterious good guy; and Jason Robards is a tough guy, believe it or not. Claudia Cardinale was a good choice for the woman, but Leone directs her too passively; in "Cartouche," she demonstrated a blood-and-thunder abandon that's lacking here."

A Clockwork Orange (1971)

"Stanley Kubrick's "A Clockwork Orange" is an ideological mess, a paranoid right-wing fantasy masquerading As an Orwellian warning. It pretends to oppose the police state and forced mind control, but all it really does is celebrate the nastiness of its hero, Alex.

I don't know quite how to explain my disgust at Alex (whom Kubrick likes very much, as his visual style reveals and as we shall see in a moment). Alex is the sort of fearsomely strange person we've all run across a few times in our lives -- usually when he and we were children, and he was less inclined to conceal his hobbies. He must have been the kind of kid who tore off the wings of flies and ate ants just because that was so disgusting. He was the kid who always seemed to know more about sex than anyone else, too -- and especially about how dirty it was.

Alex has grown up in "A Clockwork Orange," and now he's a sadistic rapist. I realize that calling him a sadistic rapist -- just like that -- is to stereotype poor Alex a little. But Kubrick doesn't give us much more to go on, except that Alex likes Beethoven a lot. Why he likes Beethoven is never explained, but my notion is that Alex likes Beethoven in the same way that Kubrick likes to load his sound track with familiar classical music -- to add a cute, cheap, dead-end dimension.

Now Alex isn't the kind of sat-upon, working-class anti-hero we got in the angry British movies of the early 1960s. No effort is made to explain his inner workings or take apart his society. Indeed, there's not much to take apart; both Alex and his society are smart-nose pop-art abstractions. Kubrick hasn't created a future world in his imagination -- he's created a trendy decor. If we fall for the Kubrick line and say Alex is violent because "society offers him no alternative," weep, sob, we're just making excuses.

Alex is violent because it is necessary for him to be violent in order for this movie to entertain in the way Kubrick intends. Alex has been made into a sadistic rapist not by society, not by his parents, not by the police state, not by centralization and not by creeping fascism -- but by the producer, director and writer of this film, Stanley Kubrick. Directors sometimes get sanctimonious and talk about their creations in the third person, as if society had really created Alex. But this makes their direction into a sort of cinematic automatic writing. No, I think Kubrick is being too modest: Alex is all his.

I say that in full awareness that "A Clockwork Orange" is based, somewhat faithfully, on a novel by Anthony Burgess. Yet I don't pin the rap on Burgess. Kubrick has used visuals to alter the book's point of view and to nudge us toward a kind of grudging pal-ship with Alex.

Kubrick's most obvious photographic device this time is the wide-angle lens. Used on objects that are fairly close to the camera, this lens tends to distort the sides of the image. The objects in the center of the screen look normal, but those on the edges tend to slant upward and outward, becoming bizarrely elongated. Kubrick uses the wide-angle lens almost all the time when he is showing events from Alex's point of view; this encourages us to see the world as Alex does, as a crazy-house of weird people out to get him.

When Kubrick shows us Alex, however, he either places him in the center of a wide-angle shot (so Alex alone has normal human dimensions,) or uses a standard lens that does not distort. So a visual impression is built up during the movie that Alex, and only Alex, is normal.

Kubrick has another couple of neat gimmicks to build Alex into a hero instead of a wretch. He likes to shoot Alex from above, letting Alex look up at us from under a lowered brow. This was also a favorite Kubrick angle in the close-ups in "2001: A Space Odyssey," and in both pictures, Kubrick puts the lighting emphasis on the eyes. This gives his characters a slightly scary, messianic look.

And then Kubrick makes all sorts of references at the end of "A Clockwork Orange" to the famous bedroom (and bathroom) scenes at the end of "2001." The echoing water-drips while Alex takes his bath remind us indirectly of the sound effects in the "2001" bedroom, and then Alex sits down to a table and a glass of wine. He is photographed from the same angle Kubrick used in "2001" to show us Keir Dullea at dinner. And then there's even a shot from behind, showing Alex turning around as he swallows a mouthful of wine.

This isn't just simple visual quotation, I think. Kubrick used the final shots of "2001" to ease his space voyager into the Space Child who ends the movie. The child, you'll remember, turns large and fearsomely wise eyes upon us, and is our savior. In somewhat the same way, Alex turns into a wide eyed child at the end of "A Clockwork Orange," and smiles mischievously as he has a fantasy of rape. We're now supposed to cheer because he's been cured of the anti-rape, anti-violence programming forced upon him by society during a prison "rehabilitation" process.

What in hell is Kubrick up to here? Does he really want us to identify with the antisocial tilt of Alex's psychopathic little life? In a world where society is criminal, of course, a good man must live outside the law. But that isn't what Kubrick is saying, He actually seems to be implying something simpler and more frightening: that in a world where society is criminal, the citizen might as well be a criminal, too.

Well, enough philosophy. We'll probably be debating "A Clockwork Orange" for a long time -- a long, weary and pointless time. The New York critical establishment has guaranteed that for us. They missed the boat on "2001," so maybe they were trying to catch up with Kubrick on this one. Or maybe the news weeklies just needed a good movie cover story for Christmas.

I don't know. But they've really hyped "A Clockwork Orange" for more than it's worth, and a lot of people will go if only out of curiosity. Too bad. In addition to the things I've mentioned above -- things I really got mad about -- "A Clockwork Orange" commits another, perhaps even more unforgivable, artistic sin. It is just plain talky and boring. You know there's something wrong with a movie when the last third feels like the last half."

filmbuilder's rating:

Roger Ebert was the best movie critic ever. But we can't all agree 100%. Here are some movies that everyone liked - except him. NOTE: I am not trying to trash him

You are allowed to argue in the comments but if you trash him, your comments will be deleted and you will most likely be blocked.

If you have any suggestions, let me know

You are allowed to argue in the comments but if you trash him, your comments will be deleted and you will most likely be blocked.

If you have any suggestions, let me know

Added to

People who voted for this also voted for

Movies I've watched in 2014

Film Journal - April 2014

Films that made me rate them higher

Xbox 360 Games I've played

Favorite to least favorite films 2014

20 Wrestlers I consider "OVERRATED".

Movie Watch: April - June 2014

My Top 10 Pink Rangers

20 Good SERIAL KILLER Flicks you might have missed

8 incredible games of 2013

Unbelievable beauty

Rappers I used to like

Movies rewatched in 2014

Most Successful Movies of... Orlando Bloom

Worst Movies of 2013

Willy Wonka Vs. Charlie

Rip-offs

Movies That Use The F-Word The Most

What Age Was This Made For?

Movies I Don't Like But My Friends and Family Do

What's Wrong With Movies? - SPOILER ALERT

Movies I Like But My Friends and Family Don't

Login

Login

588

588

7.4

7.4

7.5

7.5