Prehistoric Mammals

Add image to section

Add image to section

Bear dogs

Despite being named bear dogs, members of this family were neither bears nor dogs, but a group of their own that was related to both. Fossilised footprints of larger species show that they walked much like modern bears, their feet flat on the ground and moving the two left legs and two right legs together alternately. Smaller species lived in underground dens, and could probably burrow for prey if it outran them. Bear dogs were commonly found in Eurasia during the Oligocene, but also spread to North America where they would have fed on small rodents and rabbits, possibly climbing trees in pursuit of some prey.

Add image to section

Add image to section

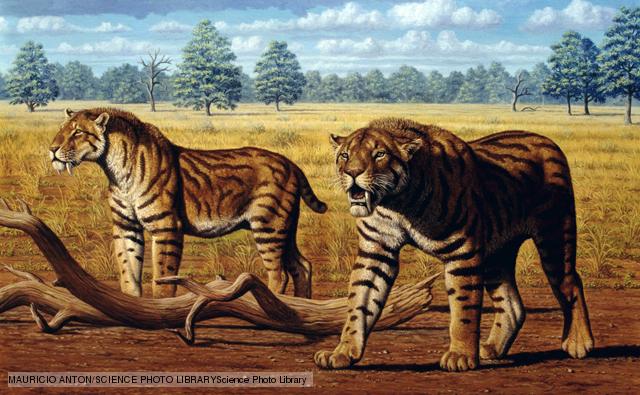

Smilodon

Smilodon, was one of the few sabre-toothed cats that would have encountered humans. Whilst sabre-tooths in Africa and Europe became extinct before our species had evolved, Smilodon survived until the end of the ice age. Three species lived in the Americas over time. The ancestors of the Native Americans might have met two of these, Smilodon fatalis and Smilodon populator. The latter was a heavily built animal, weighing more than a Siberian tiger. Smilodon's ancestor was probably another sabre-tooth species, Megantereon, that lived in Africa, Eurasia and North America.

Add image to section

Add image to section

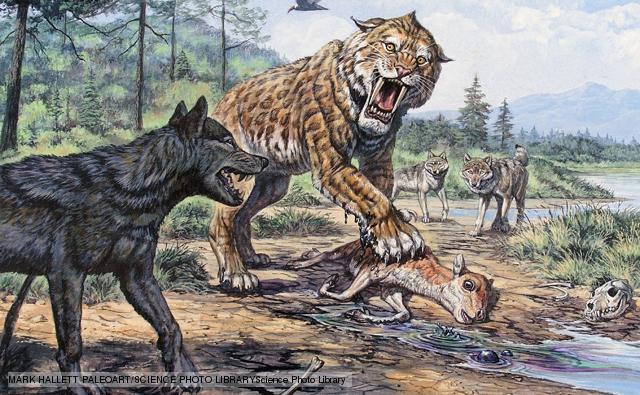

Dire wolf

The dire wolf was probably the heaviest canine ever to have existed. It earned its 'dire' tag from comparisons with the modern grey wolf. A much heftier beast with larger teeth, its powerful build and short legs indicate it might have been more of an ambush hunter and less of a long-distance runner than modern wolves. Despite being heavier, the dire wolf had a smaller brain than the grey wolf. Dire wolves were native to the Americas and thousands of their skeletons have been found in the La Brea tar pits. They became extinct between 16,000 and 10,000 years ago in different areas of the Americas.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Neanderthal

Neanderthals looked much like modern humans only shorter, more heavily built and much stronger, particularly in the arms and hands. Their skulls show that they had no chin and their foreheads sloped backwards. The brain case was lower but longer housing a slightly larger brain than that of modern humans. As almost exclusively carnivorous, both male and female Neanderthals hunted. Evidence of a huge number of injuries - like those sometimes seen in today's rodeo riders - suggests that hunting involved dangerously close contact with large prey animals.

Add image to section

Add image to section

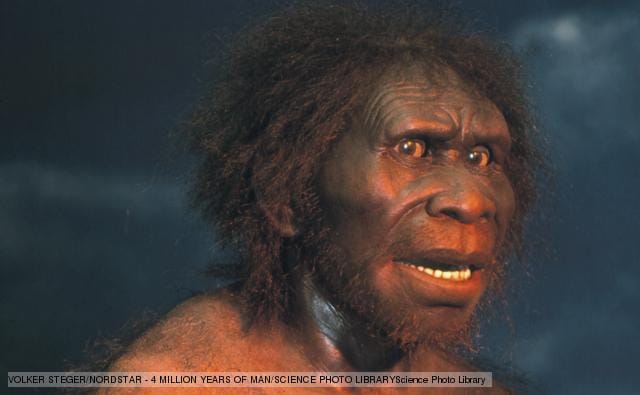

Homo erectus

Debate continues over whether Homo erectus is a human ancestor. If Homo erectus and Homo ergaster are identified as separate species, Homo erectus would be a sibling rather than a true ancestor. Homo erectus was a successful, long-lived species that migrated out of Africa. Possibly the first humans to live in hunter-gather societies, they also used rafts to travel the oceans. One of the first specimens identified as Homo erectus was the Java Man fossil discovered in 1891. Orginally named Pithecanthropus erectus, it was not recognised as a close human relative at first, as old theories held that our ancestors would have had human brains and ape-like bodies, rather than the converse.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Australopithecus

Australopithecus are the ape-man ancestors of humans and the first in our lineage to have walked upright as a matter of course. As many as nine different species of Australopithecus may have existed from 2-4 million years ago in Africa. The species with hefty jaws and massive faces - known as robust australopithecines - are believed by many scientists to belong in a separate genus, Paranthropus. In all australopithecines the males were up to twice the size of the females. However, even the largest male was quite short compared to modern humans, at only 150cm tall.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Weighing some 20 tonnes and standing 5.5 metres at

Weighing some 20 tonnes and standing 5.5 metres at the shoulder, Paraceratherium currently holds the record as the largest land mammal ever identified. It was a relative of the rhinoceros, belonging to a family of hornless rhinos, but had a giraffe-like lifestyle, feeding on the leaves of trees. Paraceratherium also goes by the names of Indricotherium and Baluchitherium, as the fossil discoveries have been given many different names. There were several different species of Paraceratherium.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Woolly rhinoceros

When woolly rhinoceros horns were found in Russia during the 19th century, many believed that the strange-looking objects were the claws of giant birds. Frozen carcasses found since in Siberia completed the picture. The horns are worn down on the under surface which suggests they were swept back and forth sideways on the ground. This may have been to help clear snow off the grass, or as part of a ritual display, as in some modern rhinos. The woolly rhino's closest living relative is the Sumatran rhino.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Propalaeotherium

Fossilised pregnant Propalaeotherium remains show that the females bore a single foal at a time. One of the earliest horses, these little forest animals had four small hooves on their front feet and three on the back. They walked on the pads of their feet, like cats and dogs. There were two species, one slightly larger than the other. More than 35 beautifully preserved specimens of the two species are known from the Messel shales, and they are also found at the nearby site of Geiseltal in Germany.

Add image to section

Add image to section

American mastodon

The elephant-like American mastodon was a distant relative of the mammoth, with whom it shared its ice age home. There have been over 200 mastodon fossil finds across North America, but they seem to have been most common along the eastern seaboard and in an area immediately south of the Great Lakes. In 1977, a unique find of a complete mastodon was made in Washington State. A human-made spear point was found embedded in the ribs and further investigation showed that the bones had healed around the spear point. This suggested that humans had attacked this animal, but that it had survived and died much later of old age.

Add image to section

Add image to section

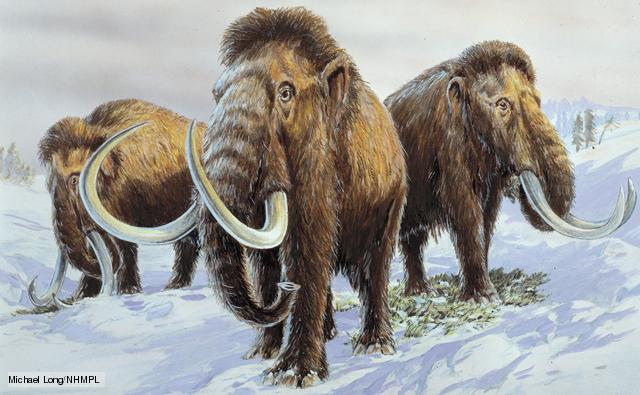

Mammoths

For hundreds of years, mammoth bones found in Europe were thought to be the bones of giants. Around 300 years ago they were identified as belonging to elephants which caused more confusion. Eventually, when it was accepted that animals that differed from those seen today had once existed, the anatomist Georges Cuvier correctly proposed that the bones belonged to an extinct form of elephant. The earliest mammoths recorded date from over four million years ago, and the larger species died out a mere 10,000 years ago. The reasons for their demise remain unclear but may have involved climate change and the arrival of human hunters.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Columbian mammoth

Columbian mammoths had impressive, spiralled tusks that measured up to 4.9m, making them world record holders amongst the elephant family. There is some debate as to how hairy Columbian mammoths were and some scientists suggest that they had a full fur coat, like the woolly mammoth's. It is more likely that hair grew more extensively on some parts of the body, such as the top of the head, but that they were basically elephant-like with exposed greyish skin. Columbian mammoths ranged through the southern half of North America and south into Mexico before becoming extinct approximately 12,500 years ago.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Woolly mammoth

A great deal has been found out about woolly mammoths from analysis of carcasses frozen in the Siberian permafrost and from depictions in ancient art. They were built like elephants, but with adaptations to prevent heat loss - tiny ears, short tails and a thick coat of dark brown hair. On the underbelly, the hair grew up to a metre long and was probably shed in the summer. Their trunks ended with two 'fingers' that helped pluck grass. Humps of hair and fat behind the head made the shoulders seem higher than the pelvis. However, the front and back legs were actually about the same length.

Add image to section

Add image to section

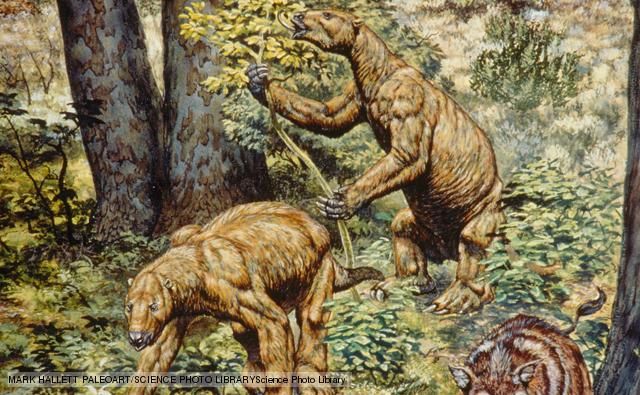

Giant ground sloths

Although related to modern tree sloths, giant ground sloths resembled no other animal: they lived on the ground, rivalled the mammoths in size and were some of the strangest mammals ever. Their remarkable claws were up to 50cm long, the size of a man’s forearm. Massive hind quarters gave way to much slimmer shoulders and a tiny head. Originally from South America - fossils have been found in Argentina - giant ground sloths spread north to the southern part of North America. Slight differences in fossils from South America suggest that males and females may have differed in size and/or appearance, which hints at a gender-based social structure.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Cetartiodactyla

It may seem that mostly land-dwelling even-toed ungulates such as giraffes and deer have little in common with exclusively aquatic whales and dolphins. However, recent scientific evidence suggests that cetaceans may have evolved from even-toed ungulate ancestors. Shared origins can now be seen within the fossil record, with early cetaceans possessing a specialised ankle bone that brings together Cetacea and Artiodactyla into a mammalian superorder, Cetartiodactyla. This groups the largest animal ever to have lived (the blue whale) together with the tiny, 2kg mouse deer.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Even-toed ungulates

Add image to section

Add image to section

Deer

Add image to section

Add image to section

Irish elk

Despite its name, the Irish elk was found all across Europe and Asia, and in North Africa, and is technically a deer rather than an elk. It is famed for the size of its antlers, which spanned up to 4.3m and weighed 45kg. Irish elk fossils are found in large numbers in Ireland's peat bogs and many are of males that suffered from malnutrition, which suggests they lived a life much like today's red deer spending each autumn fighting for the right to mate. The Irish elk's skeleton suggests that it was an endurance runner that could wear out predators without tiring itself.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Entelodonts

Entelodonts spent a lot of time fighting with their own kind. Many entelodont skulls have very severe wounds - some have gashes up to 2cm deep in the bone between the eyes - which can only have been inflicted by other entelodonts during fights. In fact it seems to have been quite common for one to fit another's head entirely in its mouth! The bony lumps all over their faces, like those of modern warthogs, were designed to protect delicate areas during these fights. This seems to have worked well, since even very scarred entelodonts show no damage to the protected eyes or nose.

Add image to section

Add image to section

Whales, dolphins and porpoises

Whales, dolphins and porpoises belong to the order Cetacea. These are aquatic mammals that have streamlined bodies highly evolved for swimming. Their hind limbs have become vestigial as part of this streamlining. All whales, dolphins and porpoises are cetaceans, including the biggest animal ever to have lived - the blue whale.

Load more items (7 more in this list)

Login

Login