Like many great works of art, The Circus had a difficult birth. Born from a period of transition when Chaplin’s main form of artistic expression was turning from silent clowns to sound-and-visual spectacles, when his personal life was crashing all around him, and from his artistic perfectionism at all odds.

Until recently The Circus didn’t come up in the conversation about the greatest of Chaplin’s films, for whatever reason it had been deemed a minor triumph at best. Why that is, I have no clue. Could its scant running time have something to do with it? It runs barely over an hour, but just because it barely qualifies for feature length doesn’t mean it isn’t an exquisite series of segments which flow together beautifully, because it is. Could it be because it was released in-between acknowledged masterpieces The Gold Rush and City Lights? That seems like a silly reason. Or could it be because The Circus came out shortly after The Jazz Singer and was the last of Chaplin’s films to be entirely silent? His Tramp here feels a bit more existential and morose than the balletic comedian with delusions of grandeur in, say, Modern Times. Or could it be that since it was born from the collapse of one marriage and the troubled start of another, and that he knew his days as a mute comic were done, and that he made a point of not mentioning it in his autobiography, that popular culture followed suet and just left The Circus to be a footnote in his filmography? The true answer probably lies in some combination of them all. But it’s grossly unfair.

Let us speak of the plot now, which isn’t really a strong narrative rush forward as it is a brilliant string of comedic, sentimental and dramatic set-pieces which ebb and flow together so fluidly and beautifully. The Tramp is accused of stealing, not entirely wrongly, and escapes into a hall-of-mirrors and later a circus for refuge. As he stumbles blindly into an ongoing performance the crowd erupts into laughter and jubilant at the hilarious and hapless clown. Sensing a gold mine as long as he doesn’t know that he’s the star and so funny the ringmaster offers him a job. The Tramp quickly meets the ringmaster’s daughter, strikes up a friendship with her, generally runs amok in the circus, and helps her escape from the tyrannical rule of the ringmaster by helping her find true love.

To say that the Tramp is a Holy Fool is an understatement. He puffs his chest out and carries himself as a noble figure filled with an intelligence bought from the finest schools. But he’s also totally helpless and hapless with each situation he gets himself into by incorrectly reading body language and human interactions. Yet somehow, someway he can help those he interacts with, he can profoundly alter and change their lives. Paulette Goddard’s characters in Modern Times and The Great Dictator and the blind flower girl in City Lights are part of the rich tradition of the Tramp’s idiot savant redemptive powers.

And it is through his ability to transcend their lives but remain left behind and forgotten by the end that I mention this film as something of an elegy. An elegy not just for the great silent-film clowns like Chaplin but also Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, and possibly even for silent films themselves and the actors that the advent of sound just steam-rolled over. And since the advent of sound the great art of pantomime and vaudevillian slapstick, frat falls and acrobatic comedy has never really regained its composure. Chaplin had a background in these things, and perhaps he knew that with the advent of sound that film would move into fast-talking screwball comedy which played just as much with quips and acidic words as it did with a performer’s ability to fall and dangle with a dancer’s grace. Cary Grant and Katharine Hepburn in Holiday and Bringing Up Baby came close, but falls nowadays have more to do with our collective schadenfreude than anything close to grace and wit.

But I am making the movie sound like some kind of overtly symbolic dramatic bore. There are so many wonderful comedic pieces to discuss. From his escaping the cops and pretending to be an animatronic figure who only attacks when his figure would logically do so through his repeated movements to the hall-of-mirrors sequence which has only been equaled by Orson Welles’ conclusion to The Lady From Shanghai, the comedy comes fast and furious and sometimes armed with sentimentality and pathos to match. Ah, yes, sentimentality, a word and emotion that has somehow become a symbol for everything cheap and easy. I beg to differ. There is nothing wrong with something that aims for good humor and bringing joy to others. The problem is that it is so rarely as well done as it is here nowadays.

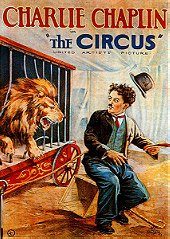

But the real highlights of the film come in two sequences which mix high emotional stakes, danger and an artist’s breathtaking commitment to entertain his audience at all costs. The first of which sees the Tramp accidentally getting himself locked into a lion’s cage. As the beast sleeps the Tramp proceeds to pass out, check the side of the cage to see an angry tiger, drop metal plates, ask for help, get cocky and finally come running out screaming after the lion roars. Who saves him? Why, the ringmaster’s daughter, of course. The tension that he builds the entire time is amazing. That is a very real lion, and he is very obviously locked in a cramped space with it. When he comes running out, limbs flailing madly, the release is ecstatic.

The other is, of course, the climax of the film in which the Tramp performs a high-wire act to impress the girl he loves so dearly. Why a high-wire act? Because she has fallen in love with the circus’ high-wire stunt performer and he wants to win her back. He attaches a harness to himself, which breaks once he gets up there, and a pack of monkey’s attack him, which he released by accident earlier in the film. His clothes fall off of him and his dignity is at a loss. The audience stands up in a combination of joyous ovation and overwhelming dread. There is but one man sitting and eating popcorn, bemusedly smiling at the Holy Fool before him willing to die for his entertainment. That one scene probably more poetically and artistically captures my entire argument than the numerous words and paragraphs I have dedicated to it. Despite the alleged 200 takes to film the scene Chaplin made it all look so artful and effortless.

Login

Login