Fifty years after its release, Steven Spielberg's Jaws remains one of the greatest scare-thrillers in Hollywood history, and it is an essential cinematic artifact. Central to the film's brilliance are the riveting suspense, the colourful characters, the sharp humour, the involving dialogue, the unforgettable score, the thrills, the incredible sense of pacing, and the way it taps into the most primal of human fears: fear of the unknown. An adaptation of Peter Benchley's best-selling 1974 novel, Jaws was the motion picture that changed Hollywood. The first film to gross over $100 million in domestic ticket sales, Jaws was seen (and seen again) by more than 70 million viewers throughout its monthslong theatrical release in 1975, spending fourteen weeks at number one, and its success inspired the enduring Hollywood trend of summer blockbusters. The film also catapulted director Steven Spielberg out of relative obscurity and onto the A-list, paving the way for the filmmaker to attain his now-legendary status. Benefitting from gripping set pieces and first-class technical execution, the power and excitement of Jaws never seem to diminish with age.

A New Yorker, Martin Brody (Roy Scheider) relocates to the small New England community of Amity Island with his wife, Ellen (Lorraine Gary), and their two children. Serving as Amity's Chief of Police, the job is quieter than New York City, but this changes in the lead-up to the island's lucrative summer season. On the week before the fourth of July, a monstrous, 25-foot great white shark chooses Amity Island as its private feeding grounds, leading to the brutal deaths of two swimmers. Although Brody is determined to close the beaches in the interest of public safety, Mayor Larry Vaughn (Murray Hamilton) wants to protect the town's reputation as a popular summer holiday destination and is satisfied that there is no more danger after a group of fishermen catch a tiger shark. However, after another attack occurs in front of hundreds of beachgoers, Mayor Vaughn is forced to accept that the shark is still out there, and he agrees to hire a contractor, veteran shark hunter Quint (Robert Shaw), to address the problem. Brody accompanies Quint, while young shark expert Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) joins the hunt. Setting out on Quint's boat, the Orca, the men lure the monstrous shark away into open water where they intend to kill it.

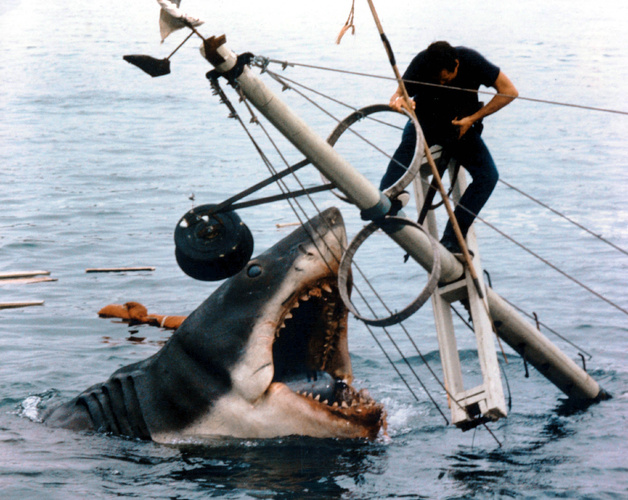

Producers Richard D. Zanuck and David Brown took a chance on hiring the 26-year-old Spielberg, a relative unknown at the time who had previously directed the made-for-TV Duel and one theatrical feature, The Sugarland Express. Spielberg was captivated by Peter Benchley's novel, and he rallied hard to get the job, but the young filmmaker was unprepared for the insurmountable challenges ahead. 21st-century filmmaking is a more straightforward process with advancements in digital effects, but making Jaws involved old-school filmmaking: practical effects, shooting on location, and mechanical sharks. The studio scheduled a 55-day shoot with a $3.5 million budget, but principal photography lasted for 159 days, and the budget nearly tripled. Bad weather at Martha's Vineyard hindered the production, shooting on the open ocean presented numerous challenges (the Orca once began to sink, sailboats drifted into frame, and equipment got wet), and there were endless troubles with the mechanical sharks (nicknamed Bruce, after Spielberg's lawyer) that malfunctioned in salt water. On a bad day, Spielberg could not shoot a single scene. It is a miracle that Spielberg actually managed to finish filming despite the overwhelming odds, and the resulting picture is a classic case of art through adversity.

For its first hour, Jaws is an exercise in escalating tension. Spielberg heavily favours the "shark's eye view" instead of showing the shark, while John Williams's chilling, memorable score amplifies the unease and anticipation. The suspense is almost unbearable as we wait for something to happen, reflecting the words of the Master of Suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, who famously said, "There is no terror in the bang - only in the anticipation of it." However, while Spielberg adheres to this adage, he also creates shock through several surprising jump scares that do not feel cheap or lazy. See, for the film's first half, musical interludes indicate that the shark is near, but one of the most shocking moments involves the beast emerging with no musical interlude or build-up. Another scene featuring a corpse in a wrecked boat was notably disconcerting for audience members at the time, even though it looks tame by contemporary standards. Spielberg pushed the picture's PG rating to the brink during the shark attack scenes, but the violence remains tactful instead of exploitative, and the director wisely leaves things to the imagination. We do not need to see the shark swallow its hapless victims, as it is more haunting to simply see someone disappearing beneath the crimson-tinted waves.

Spielberg hits the ground running with a horrifying opening attack sequence when the shark preys upon a young female swimmer (stuntwoman-turned-actress Susan Backlinie). The shark remains a menacing, unseen presence during the attack, making it unclear when it will strike. In other scenes, Spielberg implies the shark's presence through a piece of a jetty, the yellow barrels, or the menacing sight of a dorsal fin. Only providing fleeting, unclear glimpses of the shark during the first half works in the movie's favour, but this was not by design; instead, it was necessary because the mechanical sharks frequently refused to work. As it turns out, the nightmare of the malfunctioning mechanical sharks was a blessing in disguise because the ongoing problem forced Spielberg to rely more on creative staging and editing, as well as strong pacing and characterisation. Working with cinematographer Bill Butler (The Conversation), Spielberg's inventive camera movements elevate the most mundane scenes, from hiding cuts as people pass the camera on the beach to the iconic dolly-in-zoom-out technique (from Hitchcock's Vertigo) to emphasise Brody's unease when the shark strikes again.

Additionally, Spielberg enlivens the obligatory opening title sequence by including an underwater shot, presumably from the shark's perspective, instead of a simple black screen. Spielberg's insistence on filming Jaws on the ocean generates a captivating sense of atmosphere and reality that soundstages and green-screen effects could not come close to achieving at the time. There are minor technical goofs throughout the picture, such as noticeable continuity errors and visible equipment, but these do not diminish the experience or the illusion, thanks to the fluidity of the editing. Although the shark admittedly looks phoney at times, and there are limitations to its functions (the tail fin does not move, the eyes do not roll back during attacks), it still looks believable enough as a sinister movie monster, complete with scars, soulless black eyes, and rows of large teeth. The problems with the unreliable mechanical sharks are also not apparent in the finished film, a testament to the superb film editing by Verna Fields, who won an Academy Award for her efforts. However, despite Spielberg's immense efforts to bring Jaws to life, the Academy overlooked him for the Best Director Oscar, not even giving him a nomination. Five decades later, the decision remains baffling.

The years have not diminished the excitement of Jaws, as the set pieces featuring the shark remain gripping, from the attack sequence on the Fourth of July weekend to the shark attacking Hooper's cage. The film also incorporates footage of real sharks courtesy of Ron and Valerie Taylor, who filmed coverage of great white sharks off the coast of South Australia. But the film's crowning touch is the score, which earned John Williams a well-deserved Academy Award. The composer's efforts also won a Golden Globe, a Grammy, and a BAFTA Award. Williams has collaborated with Spielberg on almost all of his movies since 1974's The Sugarland Express, and for Jaws, he provides a rousing, tense, ominous score. The shark theme is one of the most recognisable cues in film history, with the simple dah-dum provoking unease and terror, leading to copycats and parodies. (The opening of 1980's Airplane! famously parodies Jaws.) The signature cue is as famous as Bernard Herrmann's music for Psycho's shower scene, and one can hardly think of Jaws without evoking memories of William's iconic score. Jaws earned a third Academy Award for its impactful sound design that significantly elevates the film's power. Subsequent home video remixes feature different sound effects in certain scenes, and sound neutered compared to the formidable original mono audio mix.

Jaws is notable for being a rare type of monster movie that is perpetually engaging, even during scenes not involving the shark. The shark hunt aboard the Orca is exciting, but the dialogue scenes are equally successful, thanks to the efforts of screenwriter Carl Gottlieb (a writer on TV's The Odd Couple), who adds humour and levity to the proceedings. Gottlieb even plays a small role as a local newspaper editor named Meadows. With all the production delays and setbacks, Gottlieb had ample time to revise and refine Benchley's existing screenplay draft (previously subjected to uncredited revisions by playwright Howard Sackler). The colourful bantering and witty dialogue frequently sparkles, ensuring the film never devolves into boredom or tedium. Spielberg attains pitch-perfect pacing, but not by frantically cutting from one action set piece to the next; instead, the director appreciates the value of downtime and quiet moments of contemplation that allow us to become wholly invested in these characters. Adapting from book to screen necessitated numerous changes, including removing superfluous subplots (such as Ellen having an affair with Hooper, and the Mayor being in debt to the Mafia), and it all results in a stronger, more focused film. Jaws is a rare film adaptation superior to the book, as Benchley's novel (while still a fun read) pales compared to Spielberg's tense, exhilarating blockbuster. Many of the changes initially incensed Benchley, particularly the climax that was much more sedate and unspectacular in the book, but the author eventually conceded that Spielberg successfully pulled it off. Benchley also makes a short appearance in the film as a news reporter.

Spielberg did not want to cast big names for Jaws, fearing that movie stars would distract the audience from the story. After a frustrating search to find Chief Martin Brody (Robert Duvall turned down the role, and Spielberg rejected Charlton Heston), Spielberg chose Roy Scheider (The French Connection, The Seven-Ups), as his everyman look and demeanour makes him an empathetic and believable protagonist. Scheider, who convinced Spielberg to hire him when they met at a party, also contributed perhaps the film's most memorable line in a moment of improvisation: "You're gonna need a bigger boat." Meanwhile, Richard Dreyfuss (American Graffiti) is a fantastic Matt Hooper, successfully creating an endearing interpretation of the character that differs from the novel. With the script undergoing rewrites for Hooper to suit Dreyfuss better, the actor shines in the role, conveying charm and dry wit. Dreyfuss is also well-matched with the late Robert Shaw (The Sting, From Russia With Love), and the rivalry between the two actors was genuine as they reportedly could not stand one another during shooting.

Although Shaw was not Spielberg's first choice for the Ahab-like Quint (the director wanted Lee Marvin or Sterling Hayden), the actor's colourful portrayal of the grizzled sea dog is one of the film's major highlights. With Quint's intense machismo, the character could have come across as a simplistic parody, but Jaws gives the old sea dog some genuine dimension and humanity while revealing his motivations for becoming a shark hunter. Aboard the Orca, Brody and Hooper draw Quint into talking about his experiences on the U.S.S. Indianapolis, a Navy ship sunk by a Japanese submarine during World War II, resulting in nearly a thousand deaths. Apocalypse Now screenwriter John Milius rewrote the monologue, while Shaw himself (a keen novelist) also worked to condense the intimidating eight-page speech. The scene threatened to halt the film's pace, but Shaw's performance is hair-raising as he tells the story of floating in the water for over a week with 1,100 men while sharks slowly devoured them, and Williams's score for the scene makes the monologue even more harrowing. Shaw delivered the speech in two long takes (he was famously drunk for one of those takes), with Fields seamlessly putting the footage together in the editing room, and it is the most riveting instance of acting in the entire film. Meanwhile, other cast members contribute strong support, including Murray Hamilton as Mayor Vaughn and Lorraine Gary as Martin's wife, Ellen. Gary was the wife of Universal president, Sidney Sheinberg, but the casting does not seem tokenistic; instead, Gary is pitch-perfect.

Jaws is first-rate filmmaking, pure and simple, and its influence on cinema endures in the 21st Century with annual summer blockbusters that can only hope to gross a similarly impressive haul at the box office. Despite fears that the picture would flop, Jaws grossed over $400 million worldwide (over $2 billion when adjusted for inflation) from an estimated $9 million budget, and it remains one of the most successful and profitable blockbusters in cinema history. It was the highest-grossing film in history at the time, until Star Wars dethroned it in 1977. The production spawned three sequels, each representing a noticeable decline in quality, leading Spielberg to block Universal Studios from releasing the follow-ups on home video in a box set with the original classic. Jaws also led to endless copycat pictures (from Joe Dante's Piranha to Renny Harlin's enormously enjoyable Deep Blue Sea), but nothing can compare to Spielberg's masterpiece in sheer suspense, terror, and excitement.

10/10

Login

Login