After all these years, it's still the same old story:

Iceberg 1. Titanic 0.

But at least James Cameron's retelling of the haunting catastrophe of April 14 and 15, 1912, has the grace and decency to sound a few new notes even as it derives much of its power from that old mainstay: bad things happening to other people. It's rich with the secret pleasure of watching a small, posh floating city turn into a gigantic iron coffin and slide headfirst into the deep, taking with it 1,500 of the innocent and not nearly enough of the guilty.

You sit there horrified and yet an ugly worm deep in your brain whispers: Better them than me.

Titanophiles should have plenty to celebrate and plenty to complain about. On the positive side, Cameron expensively re-creates the sinking of the ship in accordance with the latest and best theory, informed by high-tech exploration of the wreck. Thus in this film, unlike "Titanic" of 1954 or "A Night to Remember" of 1958, the ship is not shudderingly gashed by the berg but merely penetrated by a stiletto of ice, spreading 12 square feet of damage over 300 feet of hull. Thus, too, the big baby, as she goes down prow first and elevates her stern to the stars – almost as if displaying a cosmic middle finger to the God who doomed her – does in fact break in two as her brittle, frozen steel shatters, perishing not with a whimper but a bang.

Still, in his urge to simplify, fictionalize and mythologize, Cameron ignores many of the fascinations of the doomed voyage and its gallant crew and passengers. The heroic, indefatigable Second Officer Charles Herbert Lightoller, who emerged as the tragedy's hero, is nowhere to be seen, though he was everywhere that night and the last man plucked from the sea the next morning. No credit is given to the stalwart Capt. Arthur Henry Rostron of the Carpathia, who, by dashing through the ice to the site of the disaster, probably saved more lives than any other human agent. Nor is the dastardly rascal Sir Cosmo Duff Gordon, who may have bribed his way into the boats, on hand. And where is the deeply annoying Henry Sleeper Harper, who escaped with his wife, his manservant and his Pekingese while 52 children in steerage drowned? It's partially this tapestry of character weak and strong, of angels and devils in attendance, that has locked the disaster into our imaginations.

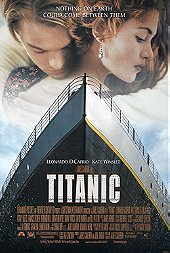

Though Cameron glimpses the actual – heroine Molly Brown, villain J. Bruce Ismay, head of the White Star Line – mostly he replaces it with a thin, nearly inane melodrama that at least feels appropriate to the era. It's as if the film were written by a scriptwriter in 1912 fresh from reading stories in Woman's Home Companion – but completely unversed in the psychological complexities of Mr. James and Mr. Dreiser. The dialogue is so primitive it would play as well on title cards. This overlay of fiction pursues an unlikely Romeo-and-Juliet coupling in which poor starving artist Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio, forever blowing a hank of hair out of his eyes) falls in love with society slave Rose Bukater (Kate Winslet, alabaster yet radiant), much to her delight and the disgust and ultimate fury of her fiance, Cal Hockley (Billy Zane). The Zane character – a Pittsburgh steel heir – inherits some of Duff Gordon's least attractive characteristics, but he's so broadly imagined a portrait of aristocratic knavery that he comes to seem almost a cartoon figure, like a William F. Buckley with hemorrhoids.

The whole framing story is a cartoon, so much so that it seems another element of doomed hubris: Cameron is a guy who thinks he can improve the story of the Titanic! He's like the producer in a famous L.A. writer's joke who knows how to make everything better. But this stroke does yield a meager benefit or two: One is a chase sequence set in the unstable bowels of the very wet ship as the witching hour of 2:20 a.m. approaches. As a device for taking a tour not only of the death of a ship but also the end of an era, it's quite efficient; as drama it's ludicrous. Moreover, Dawson is the mildest, the least threatening of rebels. He's no Wobbly or Red, not even an arty radical like Edward Steichen, just a kid who might someday sell covers to Boys' Life. Winslet's Rose is Cameron's one anachronism, a Thwarted Woman of our age thrust backward in time to represent Heroic Feminism in wild ways, such as smoking in public. Their love story is strictly for the puppies and the guppies.

It does yield a couple of amusing scenes, however: One is a kiss at the westernmost point of the ship – its very proboscis – as it steams toward New York. The clever camera captures their love and the hugeness of the structure behind them in one breathtaking shot. The other is an intellectual trope: Progressivized by her time in Europe, Rose has become a champion of the avant-garde; her newfound respect for the works of a fellow named Picasso and a chap named Freud signify her willingness to acknowledge the irrational in the universe. The manly men across the table from her – not merely Zane but also Titanic designer Thomas Andrews (Victor Garber), Ismay (Jonathan Hyde) and Capt. E.J. Smith (Bernard Hill), head man of the ship itself, a true rogue's gallery of macho hubris – stand for that late-19th-century belief that nature is tameable, that man is master, that a ship could be unsinkable. They scoff, unaware that they are about to get a tutorial from God in the form of 10,000 tons of ice.

It need not be added that the movie is very long, since everything is long this year, including the line at the restrooms. It is, in fact, about 40 minutes longer than the actual sinking (which lasted 2 hours 40 minutes vs. 3 hours 20 minutes) and quite possibly more expensive. It should be added that, despite a slow start, the thing still goes from first point to last faster than any movie in the marketplace. Once that big ol' thang begins her last swoon – about an hour into it – you ain't looking no place else and you ain't going no place else.

This is Cameron at his best. Always thin in the imagination when it comes to conceiving the tissue of character and motive (typical Cameron motive, from his first hit, "Terminator": "He kills – that's all he does"), he's the apogee of techno-nerd filmmaker. Thus the movie's central wonder is that it puts you aboard the sinking ship, palpably and as never before.

In the early going Cameron foreshadows his narrative strategy when, in a not-so-interesting setup involving greedy high-tech grave robbers visiting the Titanic's resting place 12,500 feet beneath the waves, we see a computer-animated scenario of the sinking. The rhythms of that event will be the rhythms of the movie that follows, almost exactly: a long, seemingly dead time in the water as the first three compartments of the lower hull invisibly fill; the slow tip forward as, almost imperceptibly, the bow begins to settle, then disappear; the contrapuntal stately climb of the stern amid an increasing shrapnel of falling furniture, flying glass and tumbling bodies; and the final, cataclysmic death spasm as the triple-screwed stern juts straight up, like a white whale hellbent on showing the floundering, drowning Ahabs the futility of their puny humanity, and then roars downward toward 73 long years of undisturbed silence, leaving a sea full of frozen dead and a fleet of half-empty lifeboats.

Yet in all this spectacle, the scariest element isn't the crushing power of the water and its ability to bend, drown and twist, but its creepy insistence. Watching it trickle upward (actually the boat is trickling downward), almost a teacup at a time, a thin, clear gruel of death, almost no more than you'd leave on the bathroom floor if you forgot to tuck in the shower curtain, is somehow more unsettling than watching a bulkhead go and a dozen anonymous steerage victims being swept away.

Cameron captures the majesty, the tragedy, the fury and the futility of the event in a way that supersedes his trivial attempts to melodramatize it. I didn't give a damn about cutie-pies Leonardo and Kate, much less their vapid characters or the predictable Hollywood Ten social "issues" they represent, but I left with an ache for those lost 1,500, rich and poor alike, for the big ship in ruins, and for the inescapable meaning in it all.

It is the same old story: Pride goeth before the fall, even when the fall is through 12,500 feet of black, icy water.

WP

Login

Login