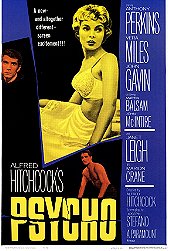

There is little to say about Psycho that hasn’t already been said. So I will begin at the start. The opening credits are sharp and searing, created by the legendary Saul Bass. The complex yet minimalist animated sequence, backed by the legendary Bernard Herrmann score, propels the viewer headfirst into a psychologically warped film. The opening score, perhaps not as famous as the shower scene music, is incredibly evocative nonetheless. This is the moment when you know you are watching a good film. It gets uphill from there. Psycho goes from strength to strength, building blocks climbing to the suspenseful peak.

We are introduced to the unconventional leading woman; the first time we see her, she’s wearing nothing more than a bra and a skirt. Yet Marion Crane isn’t simply a subject of what Laura Mulvy would call the Male Gaze. Instead, she is presented as stronger than that. She isn’t being taken care of, rather she is taking care of her financially compromised lover. After stealing some money from her job, a suspenseful trip cumulates as she reaches the Bates motel.

We soon discover, though, that the previous suspense is nothing compared to what else is in store. It’s from here that the film truly develops legs. Marion and as a result, the ever gripped audience, meet Norman Bates, the anxious young motel owner. In perhaps the best male performance of all time, Anthony Perkins truly inhabits his role. Every little tick, every little mannerism, every word of dialogue. It was a performance of such magnitude that he was typecast from here on out. Janet Leigh and Anthony Perkins play off each other incredibly well, both appearing anxious, both for obviously different reasons. They tell a story with their body language. Crane, already nervous over her crime, is now feeling uncomfortable about Bates and his unnerving swings from polite to irritable and his troubling commitment to his mother.

Then comes the shower scene. It wouldn’t be foolish to claim this as the most famous sequence in film history. The protagonist is viciously killed by a shadowy figure in a minute long scene that left and still leaves many people too scared to take a shower. Such an unconventional turn of events was truly a daring move. Perhaps this was some sort of divine retribution, punishing her for her crimes. Murdered at her most vulnerable point. Something all men and women fear. Some may claim that this is a step back from the previously independent woman first presented to us at the start. However, what happens here is nothing different to the gangsters shot down in the Warner Brothers films of the thirties. Only this occurs mid way through the film. This was new territory. The fabulously constructed voyeuristic sequence is in itself a mini-masterpiece that has stood the test of time. Few can deny that the scene is still effective. The ingenious use of editing to create a violent slap in the face to viewers, along with the screeching violins, is a perfect example of why Hitchcock was such an indispensable figure in the film industry. His vision helped beckon a new age of film with one single scene. Something he can never be thanked enough for.

Hitchcock’s direction after the infamous scene continues to amaze, with long stretches of silence, only digetic sound present, accentuated by lucid tracking shots. We find our views and beliefs of characters shift about, uncertain of who to root for. With the protagonist gone, what now? Hitchcock cleverly manipulates our feelings through these extended scenes of quietness, the attention now shifted to the enigmatic Norman. Such understanding of the audience is something that Hitchcock excelled at. In fact, he was probably the best of all directors.

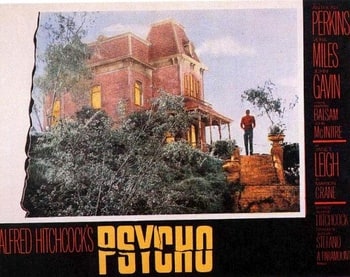

Eventually, we are lead to a strong climax, after many mysteries are explored and many twists are turned. The final twenty minutes is one big chilling finale, so taut and well wrapped that it’s almost claustrophobic. The performances are pitch perfect and even if they weren’t, no one would notice, since Perkins would draw us away from any faults. He shines. He is the epitome of a flawless characterisation. Something that many ignorant award ceremonies seemed to ignore. If there is a reason not to trust the Oscars, this probably tops the list.

The film is an example of true craftsmanship. The screenplay by Joseph Stefano, based on the novel by Robert Bloch, itself inspired by the true life crimes of Ed Gein, is full to the brim with intense and infinitely quotable dialogue. The psychoanalytical plot points are of hugely admirable audacity, with Freudian themes present from start to finish. It was a film way ahead of its time. The editing by George Tomasini, who had collaborated with Hitchcock on many of his other masterpieces such as Vertigo, is one of the primary reasons that this film succeeded, the shower scene enough proof of that. The cinematography, filmed in atmospheric black and white, a stark contrast to the vivid colours of his fifties films, is one of the best in any film. Psycho would have lost some if its effect if it were filmed in the more commercially acceptable colour format. The choice to film in black and white remains one of the wisest of all artistic decisions. Then of course, there is the aforementioned score, which is without a doubt, the most important use of music in any film. Psycho is primarily Hitchcock’s genius, yet it is a film that has its strengths in the many. It truly is a film of incredible collaborative genius.

A film of immeasurable essentiality, Psycho’s influence can be seen on a number of other brilliant films, notably Blue Velvet (1986), Halloween (1978), Funny Games (1997), Chinatown (1974) and Blow Up (1966), amongst a sea of others. Psycho’s legacy is beyond impressive, a sign of a priceless classic.

10/10

Login

Login