No image greater summarizes the artistry of Buster Keaton than his placid, immobile face and body language as the front of a house falls on top of him. The Great Stone Face was as much a character as Chaplin’ Little Tramp, but while the Tramp demanded a lovability and graceful physicality, Keaton’s character was a harder, colder individual. Possessing a greater sense of daring, adventure, and thumb-biting at death-defying stunts than Douglas Fairbanks, Keaton may have been the best artist of the silent era.

No one else could, or would even dare to, do what he accomplished in his series of films. From the waterfall leap in Our Hospitality to the immaculate timing required to remove logs on the tracks in The General or the water basin gag that ending up fracturing his neck in Sherlock Jr., Keaton was clearly a madman giving it all up there on the screen. But I mean that with sincere admiration and love. What he performs onscreen appears like an invitation to death, all without the aid of CGI or elaborate post-production techniques. When a house nearly falls on Keaton, it all happened in real-time.

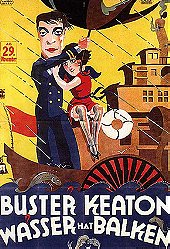

His films have more going on than spectacle. Keaton was a primary architect of his work, frequently performing uncredited directorial duties or rewrites on his scripts. Steamboat Bill, Jr. expands beyond his normal Stone Face routine, having Keaton appear first as something of a dandy before evolving into a tougher character.

The story concerns the reunion of a father and son, a love story (which feels like a last-minute thrown-in piece in comparison to the central romances of other films), and Keaton battling it out with natural forces. All of the great material is there, and much of it plays smoothly and with great efficiency, even if a slight hint of spark is missing. Steamboat Bill, Jr. is essential Keaton, but it feels like the fifth entry in a Top 5 slot. Except for the last fifteen minutes, which just obliterates the screen and threatens to take the theater with it.

Much of the preceding elements of Steamboat Bill. Jr. have a faint hint of occupying time for that marvelous special effects-ridden finale. The forbidden romance is there, but doesn’t play out with the frantic earnestness of Our Hospitality or with the goofy, sweet charm of the hapless hero of Seven Chances, it’s just there. Infinitely superior are the father-son dynamics, and many of these early cultural clashes, in which Keaton’s educated son comes into stark conflict with his blue collar father, are miniature gems. A scene in which they try on hats is amusing, and makes us miss Keaton’s pork pie hat all the more, but even better is one in which Keaton tries to smuggle a hacksaw in a pie to his jailbird dad. The comedic roundabout that ensues, with Keaton’s lovably oblivious hero, is a great bit of purely physical comedy and sight-gags.

Sadly, right after this, Keaton would make what he called his biggest mistake by signing on with MGM. After losing his artistic autonomy, his films sank into weird forms. They made money, but they lost his specific artistic voice and values. He continued to work consistently, but never with anything as remotely endearing, engaging, or marvelous as the string of films he made between 1920 –1929. But if we end the Keaton legend with Steamboat Bill, Jr. what a way to go out!

Login

Login