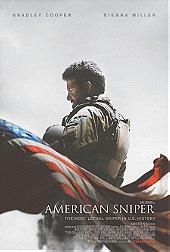

In a year filled with mediocre movies about white dudes gathering up the lion’s share of nominations from more daring and interesting movies, American Sniper may have been the blandest. A faintly sketched bit of legend printing upon which anything can be projected or read from it, American Sniper was also a film that galvanized the box office with its tasteful blandness and refusal to engage with the reality of the story. The true story is infinitely more interesting, but Eastwood has decided that the legend deserved to be printed.

Shame, as the true story of man proven to have lied in his memoirs, bragged about killing innocent people (which also turned out to be a lie), and teetered on ugly racism as the fuel for his numerous tours of duty (his social media accounts were not…well, it was pretty ugly to read) does not deserve the hero treatment. Bradley Cooper’s central performance flirts with that simmering rage and fractured mental state, but Eastwood’s story choices consistently pull away from more challenging subject matter.

American Sniper pays lip service to any moral quandary or qualms our lead has about his various horrific killings, and glosses over the lasting ramifications and emotional trauma of post-traumatic stress. PTSD is a serious issue with our veterans, they and their disorder deserve more than just meager lip service to be paid. The only scenes that really hit home are the ones in which Eastwood actually engages in the darkness. A birthday party comes to a screaming halt when Cooper’s traumatized vet misinterprets a simple scenario as something incendiary. Or the moments in which Cooper is allowed to gradually reveal the drift he feels as he tries to reengage with civilian life, a life that now feels more foreign and distant to him than the Iraqi battlefield.

A scene during a combat struggle in which Cooper is talking with his wife on a satellite phone before being interrupted by gunfire leaves her powerless and helpless as she hears the gunshots and insanity of the situation but remains powerless to help. In these all too brief moments, Eastwood manages to awaken the sleepy, blank tedium of the film with shots of real emotions and adrenaline. Maybe a better filmmaker would have found a way to make these quiet scenes of domesticity feel less like filler until the next tour of duty, the next big action scene, but not Eastwood who has a habit of taking the first draft, doing a few takes, and shooting that.

These seams show, no more so than the infamous newborn baby scene. I refuse to believe a film with this budget, and this much A-list talent involved couldn’t have found a more realistic looking doll, an animatronics, or a real baby to use for such a quick and simple scene. It’s lazy filmmaking, and it takes over the film as a whole. There was the chance to tell a more meaningful and deeper story, one that was bypassed in favor of audience pleasing go-get-‘em-kid heroics. But I suppose if I wanted a more challenging film about the Iraq War, I should turn toward the work of Kathryn Bigelow.

Login

Login