There are many ways to tackle a celebrity biographical film, typically they lean hard on the “greatest hits” approach, presenting a series of vignettes that don’t add up to a complete portrait or point-of-view as to why this artist mattered. Instead these films gloss over everything that went into crafting their public image or artistry, presenting a canonized portrait of the persona, one in which they seemed to spring fully formed from the ephemera of the culture of their time in order to move things forward. These films are tedious, and the examples of them too numerous to mention, far better are the films which zero in on one specific moment and use it to explore why this person mattered.

Capote focuses in on the titular author’s decision to take a grisly murder story he read in the newspaper, and write a book about, crafting an entirely new genre of writing in the process, while simultaneously destroying his creative muse in the process. In a sense, Capote sees both the birth of a legendary work and the moment that lead to the decades long demise of his artistic output, becoming a jet set member and frequent bon vivant on talk show appearances. The seeds of the latter are sprinkled throughout the film, while the former is the driving force of the film.

Truman Capote’s life is made up of such moments that could be made into arresting and engaging films, but it makes sense to focus in on the creation of In Cold Blood. A manageable four year period of time, which saw him go from an author of respected short stories and novels to a literary lion and white-hot celebrity, birthing the non-fiction book in the process, and the film uses this entry point to explore the complicated psychosis of the troubled writer.

Seeing a news item and a chance to create a portrait of a town dealing with tragedy, Capote’s ambitions get the better of him, driving him inextricably towards Holcomb, Kansas. For Capote, this town would grow to become the location of his eventually undoing, as he grows closer and closer to the two murders, one of whom in particular could be described as something of a (twisted) soul mate or kindred spirit. The contradiction of falling in love with one of the killers while needing them to die to create a satisfying conclusion to his book highlights the viciousness of Capote’s ambitions while also planting the seeds of alcoholic destruction and complete avoidance of his artistic craft. The film slowly shows us the broken, destructive core, a man of great narcissism, underneath the mask of a charming, impish wit and social butterfly.

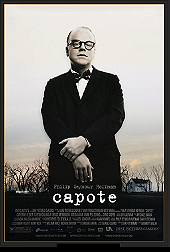

The (late) great Philip Seymour Hoffman’s essay of Capote is not an easy bit of copying mannerisms and resting on obvious twitches of a public persona. Hoffman digs deeper than normal, revealing the self-hatred in quiet moments when Capote realizes he has fallen in love with the killer while also waiting for him to die. A telling exchange occurs between him and his best friend, Harper Lee (a magnificently understated and warm Catherine Keener), where he says that there was nothing he could do to save them, and she responds with “Maybe, but the fact is that you didn’t want to.” Lee is the only character in the film who sees Capote for who he truly is, and she telegraphs it often.

Scenes of Capote gad flying about town with the rich and famous, poking fun at the rubes he’s documenting, then returning to Kansas and charming them with stories of the glitterati and movie stars display his contradictions. If one knows anything about his life, one knows that Capote’s childhood was marked by loneliness and abandonment, his public face a carefully cultivated persona to get love and attention from whoever was present. These scenes reveal that neediness and sadness. While not always a flattering portrait, Capote is fair-handed in detailing both the good and bad of a real person. What makes the film work so well, and Hoffman’s performance so perfect, is how it stares Capote’s moral and artistic disintegration straight in the eye and never flinch for a moment.

Login

Login