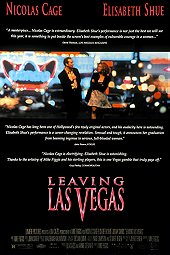

You know, I’m no stranger to depressing material, but Leaving Las Vegas is emotionally brutal, a masterpiece perhaps but absolutely devastating. It accepts that these two people will not wind up together and Nicolas Cage’s alcoholic writer will more than likely drink himself to death, and proceeds from there. When your central romantic triangle is a drunken writer, a prostitute and enough booze to fill the Pacific Ocean, we are not in uplifting territory here.

What I appreciated the most about Leaving Las Vegas was that it didn’t condemn or pander to its two central characters, rather it just took a step back and observed them in very minute and intimate detail. Writer/director/composer Mike Figgis pulls no punches in any of these respects. The moody and evocative score hammers home the point that these two needy, damaged people are only going to have the briefest piece of happiness together, they’re doomed, there is no escape here. And a scene early in their romance (if that’s even the correct wording for it) details this point explicitly. He will not ask her to stop being a hooker, she will not ask him to stop drinking, and they begrudgingly agree to this strange compromise.

It pull this moment into a wider focus, it feeds into the film’s larger scope of a hard look at dependency. Not only is she dependent on being a hooker for whatever strange reason, but she’s dependent on the drama he creates in her life, and that he’s a bigger mess than she is. He knows he’ll need a handler for his eventual drunken stupors and outbursts, and they do have a strangely sympathetic and empathetic connection to each other, so why not go along for this ride before he eventual kills himself with drink. They depend on the stability the other brings so that they can engage in their reckless behavior without fear of judgment. Their dependency exceeds beyond their obvious vices and soon becomes each other.

None of this would have been remotely watchable without the blistering work from Cage and Elisabeth Shue in the central roles. It’s easy to forget just how great an actor Cage can be nowadays since he’s devolved into National Treasure and campy work in films like Seasons of the Witch. There is none of that here, Cage is best in roles that allow him to be neurotic and twitchy, he can never be a normal person. Las Vegas gives him a role that he can fill in with his tics and odd bits of business, but Cage lets us forget that there is a human being slowly decaying before us. And Shue has never shown more depth of feeling or range as she has here. It’s one hell of a take on the hooker with a heart of gold trope, never really cracking entirely outside of cynicism or world-weariness that the character lives with day-to-day, but desperately trying to find a bit of happiness in her bleak life. It’s a shame that Shue can’t seem to find another film role as rich as this one and seems to have disappeared once more.

Leaving Las Vegas does possess a ragged charm, like its two central characters, but it’s tough stuff. It’s darkly charismatic, that’s probably the best description of it that I can summon up. It’s worth watching for certain, but don’t come to it expecting the typical Hollywood uplift and happy ending. There is no balm for any wounds here, just a good hard, unflinching look at dependency and a severely deranged romantic coupling.

Login

Login