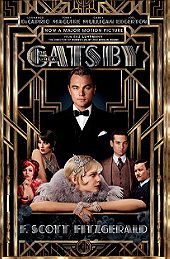

Honestly, all of the warning signs were right there for those of us ready to pay attention to them. Getting pushed back six months (roughly), the pointless decision to film the thing in 3D, the fact that Baz Luhrmann was directing and the odd decision to use hip-hop and hipster bands in a film detailing Jazz Age hedonism right before the crash. Which is to speak nothing of the very plain fact that The Great Gatsby is probably one of the hardest novels to adapt to the screen not because of its story, which is loaded with allegory and symbolism but slim on actual plot, but so much of the joy in reading and reputation of the novel resides in the clean, detailed sentences of Fitzgerald’s prose.

No amount of head-rush sugar-high visuals can properly reconnect the emotional devastation of the head of the novel or the bourgeois inertia and boredom that so many of the characters are trying to emptily fill with parties, drinks and vacuous adventures. These are creatures of money who mistake materialism for morality, they are empty-headed ciphers looking for something to give them purpose, or, at the very least, a strong drink and a good time. And Luhrmann’s film only half-way gets it right.

The frantic drop into this world is appropriately dizzying and eye-melting garish and loud. Each party scene is a decadent orgy of booze, flappers, hangers-on, glitter, streamers and fireworks. But this manic tone never lets up, and by the time the story is supposed to have rendered the emotional punches and pulled back the layers on Gatsby’s mystique and self-cultivated new identity, we feel nothing. There is no beating heart beneath the surface-level of sparkle and music video style quick cuts.

And much of the film is an out-right lie about race relationship in the 1920s. There’s a scene where a group of partiers, all of whom are black, are being driven by a white driver. It’s a moment of pure artifice made only worse by the Jay-Z song playing over it. The whole thing is almost like an apologia for Tom’s racist, xenophobic, misogynistic worldview, but an authentic view of the racial and economic realities is not exactly something Luhrmann is striving for.

Consider Nick Carraway’s cottage, a small and warm house sitting in the woods next to Gatsby’s grandiose mansion. It looks as clean and unlived in, as picturesque and large as any of the mansions. Gatsby’s brilliance is in the way that our narrator explores the wide gulf between his poor hanger-on and the nouveau riche Gatsby against the old-money Daisy and Tom. Everything is pitched at far too grand a scale for the destitution to really sink in, or for Gatsby’s remodeling of himself to carry more weight, or Nick’s first-hand experience in the oncoming stock market crash.

There’s also the problem of the white-washing, literally in this case, of the Jewish subtext of Gatsby. Born a poor Jewish boy named Jay Gatz before transforming himself through lies, revisionism and illegal activities into a wealthy WASP, Gatsby’s journey is one that recurs throughout American history. This also doesn’t bring in the problematic choice of a Bollywood actor for a Jewish gangster. What is that point of that choice? One could argue that since the entire story is told from Nick’s outsider-looking-in perspective this is his variation on that image, but that’s pretty thin an argument.

But enough about the differences between the movie and the novel, they are two very different forms, I know and understand that. As long as a movie grasps the soul and tone of the source material, everything can be forgiven. Gatsby clearly does not entirely understand it, playing like a version in which the director and writers read the back of the book and saw only buzz words and worked out from there.

At this point Luhrmann’s style has dipped into self-parody. Films like Moulin Rouge! and Romeo + Juliet could handle this full-scale assault because they’re based on an opera and Shakespeare, respectively. They’re already built in with grand emotions and theatricality whereas the Gatsby is a tender, quiet, interior novel. It buckles and strains as under the pressure that Luhrmann has placed under it. And many scenes, which are supposed to be highly involved and emotional play out as store-front windows, pretty but hollow. And the choice to have narration frequently appear on the screen is questionable at best. It ended and I let out a sigh, seeing those perfect final words emblazed on the screen were confusing for numerous reasons.

There are a few great things working for it though. The costumes and the production design are beautiful works of art. And except for Tobey Maguire, the cast is uniformly excellent. It’s not that Maguire is bad; he’s just miscast – too old for the role and alternately playing it too boyishly. But Mulligan and DiCaprio are excellent as our lovers and central players. Joel Edgerton as Tom is a bellowing rich devil, capable of charming you in disarmed awe one moment and raging and violent the very next. Isla Fisher and Elizabeth Debicki as Myrtle and Jordan are standouts. Fisher looks like Clara Bow and sounds like Betty Boop after spending a lot of time drinking whiskey and smoking cigarettes, it’s a shame that Myrtle’s screen time is so minimal. And Debicki delivers what should be a star-making performance, coming on like Katharine Hepburn in Pat and Mike and finding the right bored/frivolous/party-going tone for the whole thing.

The Great Gatsby never lives up to its title, but it’s also never truly unforgivably bad. It’s more a case of overkill and frustrating for what it omits, changes or doesn’t seem to understand. There’s a bruised but still hopeful and beating heart at the center of Fitzgerald’s prose, pity none of that could be found here.

Login

Login