With computer graphics replacing traditional, hands-on animation techniques, it is rare to behold movies brought to life through the art of claymation, for which animators painstakingly photograph plasticine puppets one frame at a time. Aardman Studios (Wallace and Gromit, Chicken Run) and LAIKA (Coraline, Kubo and the Two Strings) are among the only companies with enough patience to keep the artform alive in the 21st Century. It is, therefore, refreshing to see an Australian film like 2009's Mary and Max. The feature film debut for writer-director Adam Elliot, who won an Oscar for his 2003 short film Harvie Krumpet, Mary and Max uses claymation techniques to tell a bizarre, sweet, mature, and deeply personal story about two unlikely friends, demonstrating the possibilities of using animation to explore adult themes. Tremendously inventive, poignant, and hilarious, Mary and Max is a sublime picture of warmth and compassion about life's dissonances. The animation is superb, the characters are endearing, the humour is abundant, and it authentically delves into several topical themes.

Based partly on Elliot's personal experiences with a long-running pen-pal relationship, Mary and Max is about two people leading a mundane existence on the fringe of society who find solace in their heartfelt letters to each other. Mary Daisy Dinkle (voiced by Bethany Whitmore as a child and Toni Collette as an adult) is a chubby, friendless eight-year-old girl living in the suburbs of Melbourne with her neglectful, unsupportive parents. While at the post office with her mother, Mary discovers a New York City telephone book and looks for a random American to write to, as she is curious about the country. She selects Max Horovitz (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a severely obese 44-year-old Jewish atheist with Asperger's Syndrome living in the chaos of New York. Through their written correspondence, the two discover they have a lot in common - aside from loneliness and a complete lack of friends, they both love chocolate and a TV show called The Noblets. Thus begins a 20-year correspondence, with their friendship surviving more than the average diet of life's ups and downs.

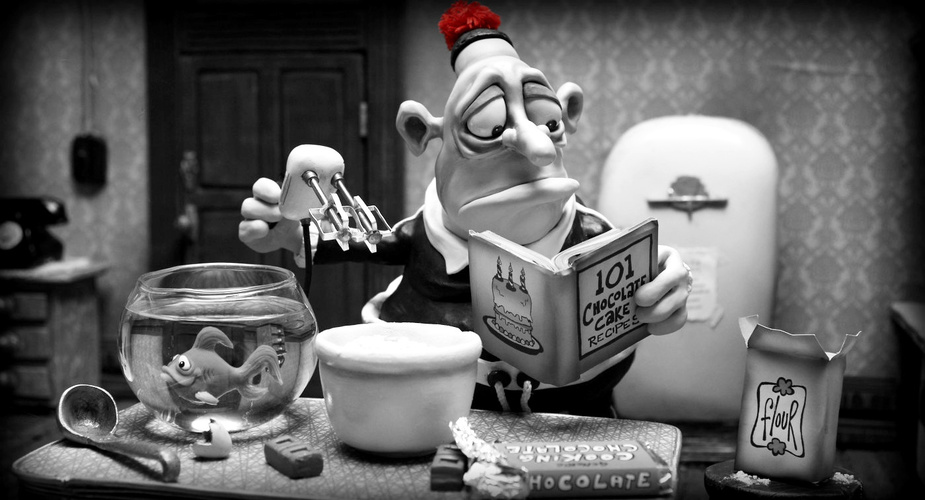

Australian legend Barry Humphries (a.k.a. Dame Edna Everage) provides an omnipresent stream of narration that gives the movie the ostensible feel of a children's tale, but Mary and Max is not for kids. The film does not shy away from an array of mature, confronting issues, such as depression, sexuality, suicide, obesity, childhood neglect, and mental illness. Whereas most mainstream movies end on a happy note and involve friendship saving the day, Mary and Max is unmistakably dark - both physically dark and dark in its depiction of reality. Max is never able to lose weight, and Mary cannot escape the shadow of her alcoholic father or kleptomaniac mother. Mary eternally resides in the brown-tinged Victorian suburb of Mount Waverley, while the movie portrays NYC as a monochrome metropolis whose only bright colours come from Mary, including a red pompom she sends her new friend. The predominantly colourless and ominous cityscape of NYC symbolises Max's melancholy, mental distress, and isolation. The ending underlines the film's dark disposition by positing that there may be happy moments in life, but happy endings are almost non-existent. But despite this, Mary and Max is not a highly depressing venture; it is a cinematic delight, with constant laughs, an abundance of heart, and several profoundly moving moments. Somehow, Elliot squeezes all of this into an efficient 90-minute running time.

It took five years to bring the visually sumptuous Mary and Max to life, with Elliot spending a year on the screenplay before storyboarding the entire feature. Principal photography took 57 weeks, with six dedicated animators working under Elliot's direction in a converted factory in Melbourne, and each animator creating an average of five seconds of footage per day with limited time and money (and no leeway for multiple takes). The smooth animation belies the film's low budget, a testament to Elliot's dedicated team, including technical director Darren Burgess, who previously worked on several Aardman productions. Subtle visual effects also effectively amplify the animation without distracting from the superlative craftsmanship of Elliot's hands-on animation team. The vivid, picturesque world is enormously impressive, with the grim landscape evoking a film-noir feel thanks to cinematographer Gerald Thompson's meticulous lighting. Every one of the hand-moulded characters is intricately and lovingly detailed, while the sets and backdrops are similarly eye-catching. The detail and intricate lighting generate the illusion of a computer-animated feature, yet the painstaking claymation process affords a look, feel and soul that computers struggle to replicate. Filmmakers must have patience and passion to undertake a stop-motion feature of such length and meatiness, but Adam Elliot exerts both qualities in spades.

Whereas Pixar, DreamWorks and Disney create light-hearted animated flicks that predominantly feature talking animals and aesthetically pleasing people, the characters in Mary and Max are flawed and human: overweight, introverted, mentally unwell, and with distinct personality traits that humanise them. Another tremendous strength is the voice cast, a cornucopia of vocal talent from Australia and beyond. Philip Seymour Hoffman is an enormously versatile actor, and he is virtually unrecognisable here, disappearing into the role of Max. This performance, therefore, reflects the true essence of voice acting - a viewer should focus on the characters instead of the actors. Meanwhile, Australian actress Bethany Whitmore (who was eight or nine years old during production) is effortlessly endearing as young Mary, giving the character an authentic vocal personality. Toni Collette also lends her talents to the production as Mary in her later years, and the veteran Australian actress brings maturity and gravitas to the role. Another recognisable name is Eric Bana, who makes a terrific impression as Mary's husband, Damien.

Through an immense aesthetic artistry and a staggering screenwriting maturity, Mary and Max authentically addresses a profound question: Is there someone for everyone? In adulthood, we understand that we are born into our families but choose our friends, and the 20-year friendship between two vastly different yet curiously similar individuals proves this notion. Adam Elliot's ambitious first feature-length claymation movie is an absolute delight, merging witty laughs with heartfelt emotion to generate this genuinely moving slice of animation with depth and substance. Mary and Max is, for this reviewer's money, the best animated motion picture of 2009 (yes, better than Pixar's Up). There is undoubtedly a place for animated movies from Pixar, Disney and DreamWorks, but we also need more brilliant movies like Mary and Max that engage, move, and make viewers think. After the terrific Harvie Krumpet and now Mary and Max, it is clear that Elliot is a highly talented filmmaker to watch.

10/10

Login

Login