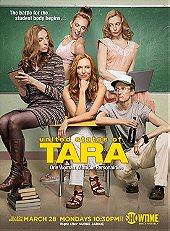

For a good portion of its run United States of Tara found that happy medium between quirk-fest and serious exploration of one woman’s psychosis. The first season is highly addictive, but a little too front loaded on the quirky marginalizing of how debilitating, dangerous and series having multiple personalities can be. And the ending of the third season gets so dark that it practically feels like an altogether different show, but that glorious middle period is what made me love it.

The main players of the show are Tara, her alters and her family. The alters allow for Toni Collette to stretch her acting muscles and show just how good she really is. She never falters for a moment and throws herself into every crazy situation with commitment and panache. Seriously, any actress who will stand in a rain poncho growling and peeing over somebody is one who deserves some kind of recognition and respect.

Her alters are a mixed bag – mostly cardboard cutouts of archetypes that she uses to escape from reality. As the series progresses more alters present themselves, and they’re presented as more organic manifestations of the buried trauma at the center of her illness. The main three are the sexually promiscuous teenager T, the 1950s ice queen housewife Alice and redneck chauvinist Buck. We’re introduced to Chicken, the person that Tara was at five-years-old, Gimme, a feral creature of pure id, Shoshanna, a New York therapist who starts to treat Tara, and Bryan Craine, the most disturbed and disturbing alter of them all. Naturally, some of them are more interesting than others. I can live without Shoshanna, and that quirky storyline goes nowhere slowly before she finally agrees to seek real help, Gimme and Chicken.

And Tara’s family is equally a mixed lot of good and bad. Max, played by John Corbett who deserved an Emmy for one of the final episodes, is Tara’s husband, who is curious about the root of his wife’s illness, very loving and devoted to her and his kids. The series does call into question why he continues to support and stay with Tara, is she a project? Is it because his own mother has mental issues and his father abandoned them? The truth of his character lies somewhere in-between these opposing theories, and if they had given him a chance to really lead an episode outside of the second-to-last one, I think his character could have been really unique. Much of Max’s action involves damage control and cleaning up after the messes that Tara has made. Why he continually allows for her to be off medication and run around freely is anyone’s guess since she clearly needs serious, long-term help. Yet that question hanging over his character it what makes him so very interesting.

Her children start life as stereotypes before getting more individualized and interesting. Their relentless pursuit of an identity and freedom from the shadow of their mother’s illness feels real, even if it does dip too far into “zany” and “kooky” territory. Brie Larson and Keir Gilchrist also have a nice chemistry together, even if they don’t look like they could possibly be related in the slightest. They sell it by how alternately supportive, loving and antagonistic they are to each other. Larson is stuck with sub-plots that feel more tacked on to give her something to do on the show than organic extensions of the main action. It’s hard to believe that her spunky, kittenish, smart Kate would happily end-up with someone older with an ex-wife and a kid. Gilchrist fares better as his gay teenager approaches a more realistic and lived-in persona than, oh I don’t know, the happy-shiny kids on Glee who must always be perfect, camera-ready and pretty-cry on command. His Marshall likes boys, yes, but he also likes other things just as much, and his coming out and obvious queerness is presented as fact and not made a big deal of.

But no family member is more overwritten or more of a contrivance to the plot than Charmaine, Tara’s sister. Rosemarie DeWitt is a phenomenal actress and she tackles the narcissistic role with glee, but I think she deserved better. It’s not until season three that we see some semblance of humanity in her character. Granted, becoming a different-kind of crazy in response to their poor parenting and traumatic childhood makes logical sense, but Charmaine is a by-product from the a snark factory in which they produce nothing but distilled consumerism and middle-class values. Much of the drama for her character is this: when will she see that Neil, played by Patton Oswalt, is her soul-mate? That someone as attractive as DeWitt winds up with Oswalt is actually nice because we see their relationship develop and evolve over time, and they have a real understanding, support and sympathy with/for each other. Yet again, much of this doesn’t happen until season three, so for much of the time she’s a vain bitch.

The United States of Tara is problematic, but I did greatly enjoy it. I found much of the humor to be sarcastic and smart. The problem is, it takes a basic premise that has rich territory for a dramedy and stuffs it with as many extraneous side-stories as possible. The main narrative is Tara and the traumatic experience at the center of her illness. The outer layer or quirk and sheer irresponsibility on the part of Max and the family to allow for her to run around un-medicated and without professional help do hamper the overall feel of the show. But in moments when we slowly discover the roots of her problems and are given a distance from Tara, that is when we truly begin to understand her. It’s the most compelling and engaging thing about the show.

Login

Login