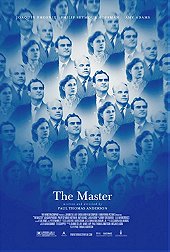

I saw The Master with my best friend, and we’re both huge fans of Paul Thomas Anderson. It seemed like the perfect combination of events. I was with the right person to discuss the film with afterward, and we were both familiar with the director’s prior work so we knew what to expect. Except, we really didn’t, because after the film ended we just looked at each other trying to figure out what we had just watched, hoping maybe the other one could give us some insight.

Months passed by, and we kept bringing it up, and eventually we decided that it was a film that doesn’t immediately strike you as something brilliant. It needs to crawl under your skin and live there for a little while as you absorb everything you’ve just seen and experienced. It doesn’t all add up neatly, but The Master was one of the best movie-going experiences I had in all of 2012. I think this could be looked back upon as a masterpiece that wasn’t properly beloved in its time.

Like any film in Anderson’s oeuvre, The Master is deliberately elliptical about numerous aspects of its narrative, preferring to burrow itself into your brain and let you parse together what is and isn’t there. There’s no definitive proof over the kind of feelings Lancaster Dodd and Freddie Quell have for each other, but there are more than a few theories and each could be backed up by the film if you look at it just so.

For me the main narrative thrust of the film is the master/mentor relationship between Freddie Quell’s raging id and Lancaster Dodd’s ego-maniacal cult leader. I don’t see a homoerotic undertone to their relationship like most people. What I see is one man seeking to stroke his own ego and prove his power by taming another man who is a figure of wild pleasures and the id given corporeal form. Getting Quell is join his group and become his devotee is nothing but a power play disguised as fatherly concern and authoritarian grandstanding.

And there’s still the oblique understanding who the titular moniker refers to. On an obvious, surface-level reading is concerns Dodd’s rank within the cult group he’s established. But within the central relationships – Quell, Dodd and Peggy, Dodd’s newest and younger wife – the power struggles muddle who is and who is not the master, as it changes over time. Is Freddie Quell ultimately the master of his own life and destiny? I suppose, in a way, the film was leading up to his self-actualization.

But how to explain the confusing relationship between Dodd and Quell, and who is the master between them? There’s an element of masochism, on an emotional level, going on there. And who has the upper-hand changes subtly and reverts back over the course of the film. And then there’s the relationship within the Dodd household. Consider Peggy’s presence, eternally playing the supportive, loving wife and lurking in the background of scenes. But there are moments when she flashes a deeper, darker undercurrent to her personality to both of the men. A scene involving a handjob quickly escalates into full-on emotional manipulation that in any other year would have given Amy Adams the Oscar.

The three central performances go a long way towards anchoring and selling the film. Joaquin Phoenix should just be handed the damn Oscar outright. No other performance this year matches his for sheer freedom and risk-taking. It was dangerously easy to dip Freddie Quell into sub-Brando caricature, think of an actor doing an impersonation of him in On the Waterfront and you’d understand, but Phoenix never even heads in that direction. His body is frequently bent and broken, his lips curled and twisted in odd ways, Phoenix finds a way to show us the disturbed, broken mind within this man. I guess some could consider him overacting, but I think his is the male performance of the year. Unafraid to look crazy or unattractive on camera, or to even be asked to do things which could make him look childish and immature, Phoenix attacks the role like I’ve never seen him do so before.

My second favorite performance in the film is Amy Adams’ Peggy. I’ve already mentioned how she keeps most of her performance at a modulated pace, preferring to keep a suburban housewife poker face and linger in the background of scenes. But when she is called to rage with fury, or go to disturbing places to illicit the results she wants, you can’t help but become slightly afraid of her. Anderson has wisely cast Adams in a part that uses her sunny, cheerful exterior that we’ve grown accustomed to, and allowed for her to promptly turn it upside down, inside out and destroy it.

And, Phillip Seymour Hoffman, who I don’t think has ever given a performance that I didn’t like. Ok, that I didn’t outright love and think was the greatest since his previous one. Here he wears a painfully bleached haircut, and frequently looks pink and bloated from too much booze. I love how fearless he is in changing his looks for a role. But it’s the way in which he erupts like a geyser that haunts you. His character is eternally on the precipice of exploding into rages and is being backed into corners by naysayers and doubtful third-parties. His ego knows no bounds, and the moment it is questioned he proceeds to lay into someone with emotional torrents while sitting perfectly still, his only movements being in his face, occasionally his hands and his voice which rises and falls so easily.

I have spent all of this time talking about the characters, their relationships and trying to make sense of it all. I haven’t even mentioned the beautiful cinematography, which should win the Oscar this year, nor the films numerous other merits. But that’s the mystery of a film like The Master, its opacity, its ability to leave so many things open-ended intrigues and fascinates and leads to long discussions afterwards. Now, this is what I call movie-making.

Login

Login