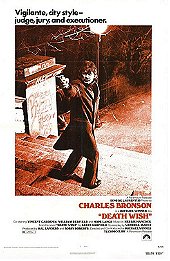

1974's Death Wish (which initially went by the apt working title of The Sidewalk Vigilante) was released at the pinnacle of Hollywood's obsession with anti-hero movies. This screen adaptation of Brian Garfield's 1972 novel is functionally simplistic, lowering itself to the cerebral level required for straight-up exploitation (though it contains a slight trace of a social commentary). The formerly timely message of this gritty actioner, along with the solid production values and Herbie Hancock's remarkable score, render it able to hold up rather confidently all these decades later. Upon release in 1974 the film was a commercial hit - it earned about $22 million at the box office (from a mere $3 million budget).

Set in New York City, Death Wish introduces Charles Bronson's signature character: a respected architect named Paul Kersey. One afternoon Paul's idyllic life is shattered when a group of street thugs (among which is a young Jeff Goldblum, in his film debut) break into his apartment, leaving his wife dead and his daughter in a catatonic state. The family is shaken to its very core after this attack. Once Paul steps onto a shooting range during a business trip intended to keep his mind off things, his vengeful instincts are awoken. The police are unable to find the hooligans that attacked his family, so Paul takes to vigilantism. He begins prowling the mean streets of New York City at night, killing all the street criminals he encounters.

Charles Bronson certainly isn't noted for his acting skills (or lack thereof), and Death Wish has no real emotional punch as a result. While the man is fairly watchable, he's so emotionless and stale, and eventually we're left wondering what really makes Paul tick. Also, the attack on Paul's wife and daughter would've been more effective if a viewer had been given the chance to know them intimately as characters. Alas, they're merely thinly-sketched narrative tools used to send Paul into vigilante mode. Other parts of the movie, however, are thoroughly effective. Director Winner stages each of Paul's confrontations like a showdown between jaded civility and total depravity. The final half of the flick mostly consists of Paul shooting criminals, but each confrontation is staged with visceral effectiveness that'll get your blood pumping (even if the silliness of the whole affair is sometimes hard to overlook).

In adapting Garfield's novel for the screen, screenwriter Wendell Mayes (who also scripted The Poseidon Adventure) altered the narrative's ultimate trajectory. Moreover, vigilantism is seen in a negative light in the Death Wish novel whereas the film unmistakably romanticises Paul's choice to take the law into his own hands. The fact that those Paul kills are portrayed as soulless criminals only adds to the attractiveness of his vendetta. This allure is further compounded by the fact that the police develop a hesitative admiration for the media-dubbed "Vigilante", and the mayor notices that Paul's activities cause the mugging rate to decrease by about 50%.

At its most basic level, Death Wish is a simple-minded vigilante fantasy and no room is left for any intellectual defence of its ideological standpoint. However the film's stance is more or less identical to that which is taken by most Westerns. Charles Bronson dispensing justice on the streets of New York is hardly unlike John Wayne or Clint Eastwood carrying out the same task in frontier outposts of the Old West. Most Western heroes are sheriffs, but they rarely operate totally within the realm of proscribed law. One could contend that times have changed, but this doesn't deflate the mythological undercurrents of "righteous justice" that transcend the slow bureaucratic processes and give both Westerns and vigilante movies their undeniable kick. The central message of all these narratives is that desperate times call for desperate measures, and sometimes a lone outsider is the only one who can get the job done. The Western likeness of Death Wish is further reinforced when Paul at one stage witnesses a mock gunfight at a reconstructed Western frontier town that's often used as a movie set (in Tucson, Arizona).

Ideology aside, Death Wish is nothing but a specific product of its time. The late '60s was a period in which street crime reached near epidemic proportions, and Hollywood retorted with reactionary films like Death Wish, Dirty Harry, and The French Connection. Characters such as Paul Kersey fill an entrenched fantasy that most people are wise enough not to try to fulfil themselves. Paul and similar characters are the epitome of cathartic excess in cinema; a means by which viewers could fleetingly revel in the delight of seeing a badass punish the wicked with righteous intensity. Director Michael Winner's tale of an epic skewing of the moral compass laid the groundwork for the dozens of films following it that had revenge as a crucial plot point. Death Wish is an excellent capsule of 1970s filmmaking - it's thrilling and thought-provoking, and it sends us off with a wink at the end.

Followed by four sequels, beginning with Death Wish II in 1982.

7.2/10

Login

Login