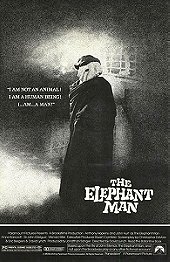

David Lynch’s second film, The Elephant Man, appears on the surface as one of his more outré works. Nary a twisty narrative that takes multiple viewings to possibly discern, The Elephant Man was nearly like Lynch going all prestige on everybody… on the surface. Peak deep enough beneath the surface and you’ll find scenes of hallucinatory beauty and a more emotive structure.

There’s plenty of facts in The Elephant Man, but there’s just as much fiction to elicit a response in the viewer as we traverse from unease at John Merrick’s disfigurement towards seeing into his soul and finding the beauty there. That combination, or combative tension to be more precise, between horror and beauty is a Lynchian trademark. Think of Blue Velvet’s pastoral suburbia giving way to the rot and festering maggots beneath the surface, quite literally.

Lynch also transitions the film from firm timelines and slow burning developments into a heady rush of incident as it goes along. Clocks and punctuality are underscored throughout the earliest scenes only to disappear as days/months dissolve into a handful of scenes that explain vast expanses of time. Once again, beneath the beautiful images and respectable costuming there’s a Lynchian sense of narrative malleability at play here. We go from dire reality to wish fulfilling social life then fold back into a terrible reality as man’s monstrous nature disrupts Merrick’s modest idyll.

It’s not as if this more impressionistic second half comes out of nowhere. Lynch opens the film with a dream-like vision of a pregnant woman attacked by elephants and throws in plenty of slow-motion circus imagery at the same time. This sequence is repeated as Merrick prepares to die at the very end of the film. His mother speaks in this bookending surrealistic sequence, quoting from Lord Tennyson’s “Nothing Will Die.” These pieces bookend the film and poetical tie it all together making a visual rhyme as mother and son suffer and die to the strands of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings.

There’s another Lynchian trademark: the easy delineation between good and evil with the setting functioning as a character onto itself. The characters of The Elephant Man are types deployed with effectiveness by a game cast. There’s the kindly doctor (Anthony Hopkins, showing flashes of his later ham years), the tough but tender matron (Wendy Hiller, bringing layers to a thinly written part), the cruel surrogate father (Freddie Jones, absolutely stellar), and the noble victim (John Hurt, completely unrecognizable but towering). We know these types well, and Lynch gets new wrinkles out of a cast that manages to find sneaky bits of business that subvert our expectations.

Hurt is the wounded heart of the film. He’s buried under layers of prosthetic makeup leaving him with little of his original self, yet he manages to project a wounded pride and soulfulness through it all. If it hadn’t been for Robert De Niro’s career-defining work in Raging Bull, I wonder if that year’s Best Actor Oscar would’ve found a different outcome in Hurt’s favor. I’m normally suspect of actors transforming underneath layers of makeup but Hurt manages to shine something through it that others do not. He makes us feel every hurt, every victory, even the inevitable peace of his death feels like the rational thought of a mind tired of being gawked at and exploited.

These make The Elephant Man clearly a piece of Lynch’s wider work, even if history and general audience reaction to it categorize as his most standard, normal film and everything else as “weird.” Reductive, to be sure, but The Elephant Man is nearly abstract in its ending run of scenes and emotional crescendos, but the presence of period trappings and actors of note like Hopkins and Hurt somehow smooth out these oddball choices. Here is the sum of Lynch’s work up to this point and various breadcrumbs of where he was about to go.

It’s easy to write The Elephant Man off as Lynch playing it straight on a surface level, but is he really doing that? Yes, it’s simple, but it’s also overwhelming in its visual beauty, surrealistic flourishes, and obscure sound choices, such as Merrick’s mother narrating over his death from the afterlife, seemingly. The Elephant Man is Lynch’s most straightforward, linear film, but that doesn’t mean it’s not in line with the rest of his work. It is very much as strong an auteur statement as Mulholland Drive or Lost Highway.

Login

Login