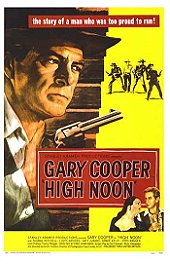

HIGH NOON, Paramount, 1952.

Dir. Fred Zinnemann. Perf. Gary Cooper, Grace Kelly and Lloyd Bridges.

Review by Dominic

Note: First-time viewers are advised that the following makes details of the film’s plot explicit.

Much reviled by John Wayne, who felt its focus on a man’s abandonment by the community around him was a metaphor for McCarthyism, Fred Zinnemann’s otherwise celebrated film High Noon sees Marshal Will Kane (Cooper) hanging up his guns as a lawman and leaving town with his new bride, Amy (Kelly), to open a store. As the deal is sealed, however, he hears word that scum-of-the-earth criminal Frank Miller, a man who has sworn vengeance against him, has been pardoned and is due to arrive on the noon train. Once reunited with his gang of three cutthroats at the station, Miller intends to ride into town and gun Kane down.

Retired, and intending to leave anyway, Kane and his wife ride out, only to turn back, at Kane’s insistence, so that he can face his aggressors. Abandoned by his impudent deputy, Harvey (Bridges), however, and unable to deputize the cowardly townsfolk, it looks as if he must face the Millers alone. As if this wasn’t trouble enough, Kane’s decision to stand his ground drives a wedge between him and his Quaker wife. Not wanting to wait an hour to find out whether she’ll be a widow, pacifist Amy threatens to leave Kane if he faces the bandits.

Despite his 1952 best actor win, Cooper’s characterization of Will Kane is beat out in fairly broad strokes. A few serious lines are either paced too bluntly, or delivered with melodramatic breaks in eye-contact and side-to-side glances. This is not all Cooper’s doing though; the actor’s relationship to the camera, generally, does not seem to have been adequately worked out, and the occasional close-up unduly exaggerates his gestures. His character’s initial introduction, prior to news of the Miller gang’s impending arrival, also seems misjudged. Confronted with the same blinky, moist-eyed act he perpetuates throughout the film, we are unsure as to why Kane should seem so visibly discomforted at this point in the story (particularly as he marries a Grace Kelly less than half his age).

High Noon’s narrative unfolds in almost real-time as the fatal hour creeps closer, and the now-iconic shots of the clock seem to expand each moment, investing it with urgency. The film’s editing is for the most part carefully handled and highly effective: a wonderful pulse-thudding montage startles us with the dread of the situation when the hour is finally struck. The opening scenes make good use of energetic and creative cinematography to perpetually reinsert the viewer into the thrust of the narrative. The film is, however, somewhat let down by the intrusive repetition of its theme-tune, which undermines the subtleties of particular scenes by explicitly cataloging basic events in the plot.

The effective use of cross-cutting easily sustains High Noon’s real-time trajectory and helps make us feel this town is a real location with a temporal life of its own. It is at the level of attributing real character to its townsfolk, however, that the film falters and allows us to question its thematic agenda.

The townspeople’s attitudes toward Miller’s gang are so inconsistent it seems implausible that they should, ultimately, behave so uniformly. These people are purposely intended to make life difficult for our hero—rather than acting of their own accord in such a way that would allow this situation to arise naturally. As the gang rides into town, people scurry in fear; one woman sanctifies the space through which they pass with a sign of the cross. Clearly these men are devils incarnate. Later, however, a hotelier admits a fondness for the Millers, whose presence made his business more profitable. The same goes for the bartender, whose patrons also liked having the Millers around—so much so that, prior to Frank Miller’s arrival, his brother rides in to town for a drink with his old friends. Despite this, when Kane attempts to raise a posse in the same bar the reason for the men’s reluctance is inexplicably given as their fear of being outnumbered, rather than that they are unwilling. In this way, the film seems to adjust the characterization of the Millers and the townsfolk’s attitude to them to suit its moral and emotional purpose: ensuring the villains are greatly feared—while having everyone still effectively end up on their side. This episode makes the townspeople’s collective failure to act seem unnaturally unanimous—a device for increasing Cooper’s isolation, inflating his bravery and sustaining this trial of his manhood.

The problem with this is that while High Noon surely purports to demonstrate how a group of people can be murderous through their very passivity, it never convincing portrays group psychology at all. The scenario it presents is a priori contrived to morally endorse a masculine ideal of independence and bravery. At the same time, one suspects the film uses Cooper’s visible moments of self-doubt to assure the viewer that because this isn’t a pretty situation what they are cheering for cannot be mere egotism and pride.

And if it isn’t egotism, it is something odorously close to it. As he famously attempts to raise a posse in the church, Kane is advised to leave town because it is his presence alone that ensures trouble. Anyway, the church-goers argue, when the new Marshal arrives, he will have the community’s full support should trouble eventuate. The film, of course, intends for us to frown on this position, and uses it to reinforce Kane’s pitiful isolation (and thus our sympathy for and identification with him). However, because the story consistently declines to clarify whether leaving would not indeed cancel the threat of violence to Amy and himself (a subject of dispute from early in the film), we cannot see that his insistence on staying is more than a matter of pride. The film’s music also seems to emphasize foremost damage to one’s own ego and reputation, with its fear that the protagonist will “lie a coward, a craven coward—lie a co-ward in [his] grave.” Despite what Kane might do, then, High Noon is insistent that some problems must be solved through violent force and, without due explanation, that this is one of them.

The construction of the bad guys is just as targeted toward testing Kane’s manhood: hardly real characters, they ride into the town as if possessed, accompanied by ominous musical themes to assure us of their inexorable badness. The problem they pose seems speculative—a worst-case scenario—rather than realistic, because the challenge to Cooper’s masculinity they bring about is what the film really wishes to focus on. An interesting variation in their appearance concerns Ben Miller (Sheb Wooley), who observes Amy from a distance as she visits the train station with an approving “Hey, that wasn’t here five years ago.” The handsome Ben shows none of the roiling antagonism and scrunched features of his fellow gang-members, and the pleasure he takes in seeing Amy seems to threaten Kane with cuckoldry more than violence: there is more to this conflict than the basic narrative seems willing to admit.

High Noon’s problematic politics are most immediately enacted through the relationship between Kane and Amy, and one of the film’s more dissatisfying moves is the arrogant dismissal of the latter’s position on the conflict in which she and her husband are embroiled (that they should leave town as originally planned and avoid the confrontation). At one point in the film, Amy gets it into her head that Kane refuses to leave because of some lingering devotion to his past love, Helen (Katy Jurado). She visits the older woman, requesting she allow her husband to go. This otherwise unnecessary plot point allows the film to use Helen to morally silence Amy with the reason her husband must stay (because he is a man who stands up for himself), enforcing the film’s dominant politics of masculinity from an apparently objective point of view.

The specific language Helen uses to do this is even more interesting. To Amy’s question of why her husband won’t leave, Helen responds: “If you don’t know, I can’t explain it to you.” This is a direct echo of Kane’s response to Harvey’s question about why he cannot be made Sheriff on a whim. In this way, Amy (the “child bride”) is associated with the explicitly childish Harvey, and her pacifism denounced as a product of her immaturity rather than treated as a legitimate philosophical viewpoint.

To be fair, the film does allow us a degree of moral ambiguity when Amy responds to Helen by recalling the death of her family through gun-violence, giving us a real sense of the trauma it may inflict. However, this ambiguity serves as a kind of rhetorical holding-bay. The film temporarily abstains from clearing up our moral ambivalence until it can do so with the kind of dramatic absolutism afforded by its finale, in which Amy rejects her pacifism by killing one of her husband’s attackers.

Prior to the climax of this ideologically questionable character-arc, Amy urgently proceeds to the scene of the showdown where she encounters the dead body of one of her husband’s assailants. This spectacle, given to us from her perspective, viscerally recalls the horror of violence she experienced as a child and led her to pacifism. Now that she has decided to do the “right thing” and stick by her husband, the corpse occurs as a faintly sadistic test of her courage. However, in a move that is surely intended to disappoint or frustrate the viewer, she fails this test: traumatized, she locks herself in the Marshal’s office alone. The viewer counts her out; in fact, her turn-around here might even render her more treacherous than before—for she decided to help her husband only to wimp out once our expectations were up. Through this, the character is maneuvered to such a point that only a violent act can redeem her in the viewer’s eyes. Not only must her passive ideology be abandoned, but she must bring herself to commit real violence in order to legitimize her devotion to her husband.

In one scene of Zimmermann’s film, Harvey overhears the bartender admit that, while he doesn’t like Kane, the man has guts. Turning to Harvey, he claims that his own decision to abandon Kane showed brains. Harvey, of course, tired of being considered but a boy, doesn’t want brains. In the world of High Noon, guts and brains are oppositional: guts are what really make the man, and the specific logic of Kane’s predicament is secondary.

This focus on the ethos of masculinity is High Noon’s real interest, and the dilemma at the narrative’s center is geared to provide a morally approved pretext for its demonstration. When questioned as to why he will not allow himself to run, Kane responds: “I don’t know.” His need to stay is something ideologically ingrained and normalized rather than ethically argued-for or justified.

Whatever High Noon’s politics, though, the film is more than a straightforward male fantasy; it takes us on a fascinating emotional and intellectual journey, lingering at a number of psychic places that we would probably prefer not to visit. If we are to share in Kane’s triumph, the film still asks we share in his doubt and, at times, piercing vulnerability. The narrative manages the passing of diegetic time and its significance masterfully, and there isn’t a moment that it fails to engage the viewer. Combined with this stylistic energy, High Noon’s controversial politics and its enduring cultural impact make it essential and discussion-provoking viewing.

10/10

Login

Login