Adaptation works wonders for Quentin Tarantino. Sure, he can’t help himself when it comes to populating his film with a sprawling running time and (so much) jive talking, but Jackie Brown remains his most mature, accomplished, and satisfactory work. There’s shocking bits of violence here, but much of it actually (gasp!) in service of a story and not just to foster his juvenile instincts or heavy-handed referential nature.

Elmore Leonard’s Rum Punch provides a solid framework, one that forces Tarantino does diverge from not only in changing Jackie’s race from white to black but in other narrative details, but it’s also a model of great adaptation work. Leonard’s economical style and Tarantino’s maximalist don’t sound like a match made in cinematic heaven, yet there’s something incredibly juicy and vibrant about their divergent styles meeting in the middle here.

Maybe it’s the way that Leonard’s style forces Tarantino to “grow up” cinematically, but there’s honest to god human emotion and recognizable characters here. Led by a stellar Pam Grier in a performance that demanded serious awards attention and a revitalization of her career that strangely didn’t come, Jackie Brown garnishes its entangled double-crosses and crime elements with a center that’s the sweetest, most humane love story in all of Tarantino’s body of work.

Unrequited and suppressed emotions run throughout Tarantino’s films, but they usually end in a big bang of violence and artful blood splatter. Think of the Bride’s near phoenix-like origins in the Kill Bill films, of the entirety of Reservoir Dogs turning in on each other, or The Hateful Eight’s long simmering grudges erupting in prolonged scenes of carnage. Jackie Brown is the most complex examination of that emotional state, and it’s most mature.

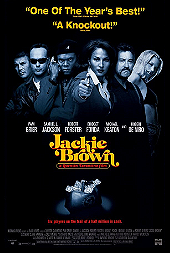

We meet Jackie as a struggling airline stewards for the low rent Cabo Air, and we quickly learn that she doubles as a drug runner for Ordell (Samuel L. Jackson, going near Brechtian but still a joy to watch) once she’s caught by the ATF and its primary detective on the case (Michael Keaton). Her bail bondsman, Max (Robert Forster), is immediately smitten, and their connection is the core of the movie. Everything else, including Ordell’s beach bimbo girlfriend (Bridget Fonda) and thug best friend (Robert De Niro, wincing and grimacing more than acting), is part of a tangled weave to keep shoving these two back together. They are the center that holds it all together.

On paper, their affection and blossoming feelings for each other shouldn’t make much sense. Jackie is the world-weary and desperate version of any of Grier’s iconic blaxploitation heroines, while Max is the ultra-buttoned up good cop. Yet there’s visible sparks from the moment they meet, and between the actor’s clear chemistry and joy in playing off each other to the fun of just watching them sit back and talk, their connection becomes our active rooting interest.

Tarantino’s always had a strong eye for casting, but he out does himself with the performances he gets from Grier and Forster. Grier is a mesmerizing presence. She’s beautiful, she’s intelligent, she’s resourceful, and she’s got one mean poker-face. Grier’s performance is master class of small bodily movements telegraphing everything for the camera. She never goes “big” because she never has to, and her transition from honest and open communication with Max to staring down danger with an impassive face is demonstrated with a mere eyebrow raising. It’s the kind of performance that would reignite a male actor’s stock and have bigger, better opportunities, I mean, look at what happened with John Travolta before he shot himself in the foot.

Just as good is Forster as Max, for which he received the film’s lone Oscar nomination. He deserved the damn thing as he’s the quiet, emotional heart to Jackie’s quick-thinking brain. He’s just as prone to underplaying his scenes as Grier, and his crinkled smile and hint of heartache in their final back-and-forth is a knockout of minute details and specific choices making a moment come alive on camera. It helps that Forster is something of an anonymous character actor, you know you’ve seen him when he pops up but his name frequently escapes you, because a bigger star in this part would’ve titled things out of balance. Forster’s schoolboy crush and conservative demeanor are deeply touching in his elliptical goodbye to Jackie.

It’s this kernel of romantic possibilities in the face of middle age that makes Jackie Brown so rewarding. It’s a great hangout movie, even if some of the diversions with Fonda and De Niro prove more distracting than humorous and glaring examples of the director’s fetish for women’s feet. Jackie Brown is also a towering achievement to the cinematic brickhouse that is Pam Grier, and she works hard for the money and adoration.

Login

Login