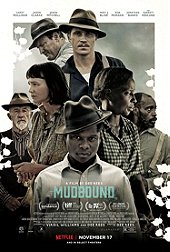

Mudbound is the sight of a filmmaker evoking the power and fury of William Faulkner’s prose. Not only in the ways that the land itself becomes a harsh character, both unmovable by the sorrows of its characters and unrelenting in its unending withholding, but in its intense examination of generational and racial conflicts. These differing fractions both within the familial units and outside of it swirl around each other, bumping into each other before the big explosive climax. Mudbound is the Southern Gothic style operating at its artistic zenith.

Economic devastation is built into the framework of southern living in certain quarters, most especially in the literature which alternates between the poverty stricken and wealthy families going to rot. Mudbound includes both in a white family that finds itself on the harsh terrain typically reserved for black sharecroppers through poor financial choices, and a black family that’s inherited the land post-Reconstruction. We step into an already volatile situation long before the cantankerous, openly racist grandfather (Jonathan Banks) seeks to entrench a social order through violent means.

Mudbound’s expansive narrative is told through the interior monologues of several characters, and equal time is presented to both the white and black families giving a full-range of voices and experiences to poverty and racism. Henry McAllen (Jason Clarke) uprooted his family from Memphis to a parcel of land out in the country, only to find that he was swindled and is forced to live in the same area as the black sharecroppers. He takes this as a humiliating blow, and frequently speaks of how cruel the land is to him and his life.

In contrast, there’s Hap Jackson (Rob Morgan), patriarch of the black family that becomes the, well, not quite friends, but find themselves tied up with the McAllens. Hap finds pride and joy in working the land that his ancestors tilled and harvested in bondage because it is now his own. He takes his sense of ownership and pride as proof that things have improved for himself and his family.

We also get the disparate world views of their wives. Laura (Carey Mulligan) is clearly too smart for her husband, and one senses that she settled for him out of a fear of becoming a spinster through societal pressures. There’s clearly tension between them as she holds onto vestiges of their old life and societal standing. She can clearly see the thin line separating her from the poor white trash of the area, and the even thinner line demarcating her privileged existence over that of her black neighbors. Much like her husband, she’s never outwardly aggressive or openly racist but she tells more than she asks and demands more than she gives in return.

For all of Laura’s tenuous grasps on keeping her family together and holding onto middle-class signifiers, Florence (Mary J. Blige) is actually a giving, suffering, equal partner in her life and marriage. She and Hap both know that they walk a precarious line around white folks of any economic status, and the change between their public and private selves is seamless through years of practice and generations of ingrained lessons. In her most private moments and thoughts, Florence is a woman with a rich inner life and potential that is clearly going under realized through racial roles and social stasis.

Mudbound’s most unique and engaging relationship is through the friendship that forms between Jamie McAllen (Garrett Hedlund), Henry’s younger brother, and Ronsel Jackson (Jason Mitchell), Hap and Florence’s oldest son. They meet while serving in World War II, and reignite a tenuous friendship when they return home. While the Confederacy may have fallen, the hideous specter of the Civil War and Jim Crow lingers in the air throughout Mudbound. Their friendship, no matter how benign, is considered an affront to a caste system that should’ve been washed out long ago.

Dee Rees has made a film of startling power and impact here. Not only does she get stellar work from her cast, the biggest surprise being Mary J. Blige’s transformative performance that digs deep into a dramatic prowess no one saw coming and Jason Mitchell’s star-in-the-making work, but she gives them a wealth of material to play both externally and internally. One of the joys of the film is watching as Rees’ camera lingers on her actors faces in close-up in the full gamut of human emotion. The sight of Blige washing Mitchell’s injured and bleeding body late in the film is remarkable for the complicated emotions Blige manages to telegraph to the viewer.

Mudbound’s final scene is set in post-war Germany, as the country reconciles its atrocities and Ronsel returns to his wartime lover after escaping the present-day violence of America’s sins and entrenched social conditions. It’s a scene of hope and a bleak smack in the face for the ways it accuses America of not taking a good, hard look at itself. This scene, like so many others, is just a part of the reason why Mudbound was one of the best films of 2017.

Login

Login