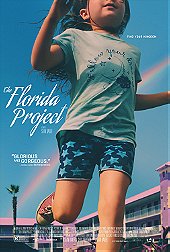

On the periphery of Disney World there’s a little motel called Magic Castle, and it is here that we begin our story. It’s the summer, and we’re quickly introduced to Moonee (Brooklynn Prince, a stunner of a child actor’s performance), a six-year-old heavily interested in playtime, imagination, and performing various mischievous acts without the forethought of where these actions will lead. The Florida Project will place us directly into her point-of-view and journey, and it’s an emotional ride of great rewards.

Moonee lives with her young mother, Halley (Bria Vinaite, another great find), at the hotel, and she quickly meets up with the new girl at the motel, Jancey (Valeria Cotto), after spitting on Jancey’s mom’s car. Moonee gets in trouble, Halley encourages Jancey and Moonee to be friends, and we’re off from there. There’s not a solid story structure to The Florida Project, we merely sit back and observe various episodes in Moonee’s life.

We watch many things occur from Moonee’s perspective, several of which we can fill in the gaps as adults whereas the details appear mystifying to her, and observe the human need for denial in full activity. Various scenes portray the bittersweet reality of these characters with a clear-eyed empathy for their humanity and the unspoken, largely unknown reasons for how and why they ended up here. There’s a refreshing lack of judgment as these characters scramble to survive, protect their kids, and maintain some semblance of dignity and humanity.

Orbiting it all is the kindly manager, Bobby (Willem Dafoe) one of many adult figures trying desperately to keep the tragedy of life at bay from the children occupying the slum motel. He performs his normal duties with lived-in ache and tiredness, but also emerges as a fatherly figure to the various denizens of the Magic Castle. Dafoe develops this subtlety and with great compassion for this man. For an actor of his stature to appear in a film populated by unknowns and first-timers could easily dip into star vanity, but no so here. Dafoe develops a rapport with them, and grounds himself into a man that expresses a decency that feels forged out of hardship and personal pain and tragedy.

His protectiveness is never more apparent than running off a man that’s hinted at being a child predator, and his rage is palpable. Even better is a scene where he runs interference between Halley, having turned to prostitution to provide for herself and Moonee after losing her meager support system, and a john. Bobby acts as a human shield between the two of them while Halley, in a bit that’s nearing slapstick but still nonjudgmental about her, telegraphs her rage and contempt through her face and flashing the john the middle finger. He not only diffuses the situation but does so in a way that’s entirely protective of Halley and Moonee. Bobby is the supportive through line of The Florida Project, an emblem of the protections in place to try and let these kids just be kids.

If Moonee understands any of these developments, you wouldn’t know it from her persistent need to play and imagine. She’s aware enough of the cultural currency at play here to know she’s not going to Disney World itself any time soon, but she finds spaces where she can pretend that they’re various locations or attractions from the theme park. Director Sean Baker allows for Moonee’s vivid imagination to play out as a nearly holy communion with something larger than herself. It’s beautiful how he simply allows her to be in these spaces and observe where her spirit and mind will take her.

Baker also manages to capture a feeling of transience to these imaginings that extends to the surroundings. Earlier in the film, Moonee and the other children say goodbye to one of their own that’s moving away. While moving away, his father makes him give away his toys to the other kids because there’s no room in the car, and the kid stands by with a curious expression on his face as these totems of his childhood and time spent here are given away. He’s learned something about the ephemerality of life despite the promise of replacing them all with brand new ones. It won’t be the same, nothing in life ever is.

This feeling carries us into the final moments of the film which play out in a curious emotional space. With Halley and Moonee being separated from each other, briefly they’re routinely told, after someone ratted on Halley’s escorting, we witness Moonee’s rage and confusion as to what’s happening. Moonee knows that something dark is descending upon her, something that will shatter the delicate nature of childhood innocence and precociousness. In a flight of desperation we watch her run with Jancey to Disney World’s Magic Kingdom. Or did they? Is this scene real or the most fully-realized bit of daydreaming we’ve witnessed to this point?

The literal truth of the scene is nearly impossible to read. She very well could have run off, but I prefer to think of this as a last-ditch effort, a moment of clearly thought-out self-preservation of her innocence, rather than any kind of literal truth. It’s a complicated moment of heartbreak and joy, underscoring the transient nature of childhood innocence, and further underlining the socioeconomic structures at play here. It’s a perfect ending to one of 2017’s best films.

Login

Login