An elderly lord abdicates to his three sons, and the two corrupt ones turn against him.

Tatsuya Nakadai: Lord Hidetora Ichimonji

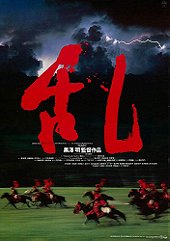

Born in 1910 Japan, Akira Kurosawa first studied painting before moving into film in the late 1930s. A well-known director in Japan throughout the 1940s, his 1950 production of Rashomon launched him to international acclaim; and throughout the remainder of his long career he was widely acknowledged as among the world's greatest film directors. The creator of such films as The Seven Samurai, Ikiru, and Yojimbo. Released in 1985, RAN would be among his final films and is generally felt to be among his finest.

In Kurosawa's RAN, the Lord Hidetora Ichimonji (Tatsuya Nakadai) divides his kingdom between three sons: Taro (Akira Terao), Jiro (Jinpachi Nezu) and Saburo (Daisuke Ryu). When youngest son Saburo upbraids his father for foolishness, Hidetora banishes Saburo, only to find Taro and Jiro turning against him just as Saburo predicted. Kurosawa shapes the story to 16th Century Japan.

As in many Kurosawa films, Ran alternates moments of great stillness with rapacious action, enclosed spaces with wide vistas. In stillness, the film focuses upon its actors and their intrigues; perhaps most notably the perfidious Lady Kaede, a truly dark character frighteningly realized.

I was personally interested with the character of Lady Kaede played to perfection by Mieko Harada. All through history women can be so much more manipulative than any man can dream of being. Some of the world's most notorious and great figures in History have sometimes been driven to make choices not of their own making due to a manipulative wife. Little suggestions or murmurs from their partner; influencing ideas within their minds that otherwise wouldn't have been thought of immediately. You can trace this recurring theme right back through the ages tracing back to present day.

Indeed, all the cast is remarkably fine. Although the greatest achievement, and the timeless performance, of the film is Tatsuya Nakadai's Lord Hidetora, whose mixture of good intention and folly leads first to humiliation and then to madness.

Hidetora Ichimonji, played by Tatsuya Nakadai, is instantly unrecognisable from his real-time manifestation. He gives a performance which results in being layered, precise and transcending realms of quality. The transition of his character during the film's running time is mind blowingly incredible.

We see a man lose everything, we see his own past and his rise to power; The many people effected by his bloodthirsty actions, by his untamed goal for ultimate domination and power. Women who have lost their families and homes, that have been claimed as the victors wives, a noble boy that has his sight taken and home destroyed along with the suffering of his sister.

The victims only peace is to pray to Buddha...but as RAN tells us, Buddha left this place a long time ago, to the world of men who ravage the lands with war and blood.

Kurosawa first came up with the idea that would become RAN in the mid-1970s, when he happened to read a parable about the Sengoku-era warlord Mōri Motonari. Motonari was famous for having three sons, all incredibly loyal and talented in their own right. Kurosawa began imagining what would have happened had they been bad.

Despite the similarities to Shakespeare's play King Lear, Kurosawa only became aware of the similarities after he had started pre-planning. According to him, the stories of Mōri Motonari and Lear merged in a way he was never fully able to explain. He wrote the script shortly after filming Dersu Uzala in 1975, and then "let it sleep" for seven years. During this time, he painted storyboards of every shot in the film, later published with the screenplay and available as an extra on the Criterion Collection DVD release of the film, and continued searching for funding. Following his success with 1980's Kagemusha, which he sometimes called a dress rehearsal for RAN, Kurosawa was finally able to secure backing from French producer Serge Silberman.

According to American film Critic Michael Wilmington, Kurosawa told him that much of the film was a metaphor for nuclear warfare and the anxiety of the post-Hiroshima age.

He believed that, despite all of the technological progress of the 20th century, all people had learned was how to kill each other more efficiently.

In RAN, the vehicle for apocalyptic destruction is the arquebus, an early firearm that was introduced to Japan in the 1500s. Arquebuses revolutionized samurai warfare, and the age of swords and single combat warriors fell rapidly by the wayside. Now, samurai warfare would be characterized by massive faceless armies engaging each other at a distance. Kurosawa had already dealt with this theme in his previous film Kagemusha, with the destruction of the Takeda cavalry by the arquebuses of the Oda and Tokugawa clans.

Akira thus concluded, ''All the technological progress of these last years has only taught human beings how to kill more of each other faster. It's very difficult for me to retain a sanguine outlook on life under such circumstances.''

In RAN, the Battle of Hachiman Field is a perfect illustration of this new kind of warfare. Saburo's arquebusiers annihilate Jiro's cavalry and drive off his infantry by engaging them from the woods, where the cavalry are unable to venture. Similarly, Saburo's assassination by a sniper also shows how individual heroes can be easily disposed of on a modern battlefield. Kurosawa also illustrates this new warfare with his camera. Instead of focusing on the warring armies, he frequently sets the focal plane beyond the action, so that in the film they appear as abstract entities.

The Japanese word for RAN results in being chaos or revolt; The story is a beautiful example of how harsh the World and humanity can be.

As the title suggests, chaos occurs repeatedly in the film; in many scenes Kurosawa foreshadows it by filming approaching cumulonimbus clouds, which finally break into a raging storm during the castle massacre. Hidetora is an autocrat whose powerful presence keeps the countryside unified and at peace. His abdication frees up other characters, such as Jiro and Lady Kaede, to pursue their own agendas, which they do with absolute ruthlessness. While the title is almost certainly an allusion to Hidetora's decision to abdicate (and the resulting mayhem that follows), there are other examples of the disorder of life, what film critic Michael Sragow calls a "trickle-down theory of anarchy." Kurogane's assassination of Taro ultimately elevates Lady Kaede to power and turns Jiro into an unwilling puppet for her schemes. Saburo's decision to rescue Hidetora ultimately draws in two rival warlords and leads to an unwanted battle between Jiro and Saburo, culminating in the destruction of the Ichimonji clan.

The ultimate example of chaos is the absence of gods. When Hidetora sees Lady Sué, a devout Buddhist and the most religious character in the film, he tells her, "Buddha is gone from this miserable world." Sué, despite her belief in love and forgiveness, eventually has her head cut off thanks to Lady Kaede. When Kyoami claims that the gods either do not exist or are the cause of human suffering, Tango responds, "The gods can't save us from ourselves." Kurosawa has repeated the point, saying "humanity must face life without relying on God or Buddha." The last shot of the film shows Tsurumaru standing on top of the ruins of his family castle. Unable to see, he stumbles towards the edge until he almost falls over. He drops the scroll of the Buddha his sister had given him and just stands there, "a blind man at the edge of a precipice, bereft of his god, in a darkening world." This may symbolize the modern concept of the death of God, as Kurosawa also claimed "Man is perfectly alone...Tsurumaru represents modern humanity."

Kurosawa himself once said that "Hidetora is me," and there is some evidence in the film that Hidetora serves as a stand-in for Kurosawa. Hidetora's crest is the sun and moon, and the Japanese character of Kurosawa's first name "Akira" (kanji: 明) is combined from the kanji meaning "sun" (日) and "moon" (月).

Esteemed film critic Roger Ebert agrees, stating that Ran "may be as much about Kurosawa's life as Shakespeare's play."

RAN was the final film of Kurosawa's third period(1965–1985), a time where he had difficulty securing support for his pictures, and was frequently forced to seek foreign financial backing.

An extract from the Screenplay speaks volumes of the frustration Akira Kurosawa must have felt in this period, his wife tragically died during production, he channelled his grief into this film, and it shows: "A terrible scroll of Hell is shown depicting the fall of the castle. There are no real sounds as the scroll unfolds like a daytime nightmare. It is a scene of human evildoing, the way of the demonic Ashura, as seen by a Buddha in tears. The music superimposed on these pictures is, like the Buddha's heart, measured in beats of profound anguish, the chanting of a melody full of sorrow that begins like sobbing and rises gradually as it is repeated, like karmic cycles, then finally sounds like the wailing of countless Buddhas."

In addition to its chaotic elements, RAN also contains a strong element of nihilism, which is present from the opening sequence where Hidetora mercilessly hunts down a boar only to refrain from eating it to the last scene with Tsurumaru. Roger Ebert describes Ran as "a 20th century film set in medieval times, in which an old man can arrive at the end of his life having won all his battles, and foolishly think he still has the power to settle things for a new generation. But life hurries ahead without any respect for historical continuity; his children have their own lusts and furies. His will is irrelevant, and they will divide his spoils like dogs tearing at a carcass."

This marked a radical departure from Kurosawa's earlier films, many of which were filled with hope and redemption. Only Throne of Blood, an adaptation of Macbeth, had as bleak an outlook. Even Kagemusha, though it chronicled the fall of the Takeda clan and their disastrous defeat at the Battle of Nagashino, had ended on a note of regret rather than despair. By contrast, the world of RAN is a Hobbesian world, where life is an endless cycle of suffering and everybody is a villain or a victim, and in many cases both. Heroes like Saburo may do the right thing, but in the end they are doomed as well. Unlike other Kurosawa heroes, like Kikuchiyo from Seven Samurai or Watanabe from Ikiru, who die performing great acts, Saburo dies pointlessly. Gentle characters like Lady Sué are doomed to fall victim to the evil and violence around them, and conniving characters like Jiro or Lady Kaede are never given a chance to atone and are predestined to a life of wickedness and ultimately violent death as well.

Kurogane gives us a warning concerning the powerful persuasion and danger regarding women, in particular, aimed at Lady Kaede:

''There are many foxes hereabouts.

It is said they take human form.

Take care, my lord.

They often impersonate women.

In Central Asia a fox

seduced King Pan Tsu...

and made him kill men.

In China he married King Yu

and ravaged the land.

In Japan, as Princess Tamamo...

he caused great

havoc at court.

He became a white fox

with nine tails.

Then they lost trace of him.

Some people say...

he settled down here.

So beware, my lord, beware.''

Akira sums up the story's theme by underlining his goals from initial stages, ''What I was trying to get at in Ran, and this was there from the script stage, was that the gods or God or whoever it is observing human events is feeling sadness about how human beings destroy each other, and powerlessness to affect human beings' behaviour.''

Few directors are able to convey the sense of chaos, destruction, and fear with which Kurosawa endows battle or drama scenes; RAN is the best example to ever grace film.

There are several worthy circumstances, and the battle of the third castle (in which Hidetora is attacked by sons Taro and Jiro) is easily among the finest battle sequences of Kurosawa's career. Presented without any sound except a simple, eloquent music score, flash-cutting between different groups in the struggle, the result is a unique mixture of beauty and horror; In my opinion unequalled by any other film I've seen.

The cinematography for 1985 is unrivalled, having that timeless and radiant glow of legendary significance. Costumes and battle gear really are flawless; The cavalry riding alongside the infantry are truly inspiring to watch. The vibrant, colourful visuals, accompanied with a superlative Japanese primal score of music, strong emotionally charged performances and you have a dominant winner. The cast doesn't just say their lines, they bark them with a daunting, charged emotion that screams believability and finesse.

It should be noted that RAN, unlike Rashomon, Throne Of Blood, Ikiru and many other Kurosawa films, RAN is in beautiful splashes of colour. I have long been accustomed to the remarkable shading of Kurosawa's black and white projects, and I missed it; But only for a moment.

Kurosawa proves no less adept in colour than in black and white format, and RAN's use of colour is beautiful. For this reason I particularly recommend the Criterion Collection edition of the film over any other; it is impeccably fine. But regardless of the particular version, this is a film which must be seen by anyone who appreciates Asian or World Cinema; Truly a masterwork by a great master, Akira Kurosawa.

''Are there no gods... no Buddha? If you exist, hear me. You are mischievous and cruel! Are you so bored up there you must crush us like ants? Is it such fun to see men weep?''

10/10

Login

Login