A heinous crime and its aftermath are recalled from differing points of view.

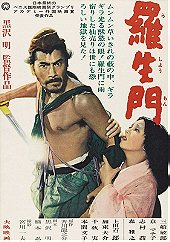

Toshirô Mifune: Tajômaru

Ironically, Japanese critics were not enthusiastic about Rashomon when it was released in 50's Japan.

In today's world, however, Rashomon is generally considered to be the film that introduced both director Akira Kurosawa and Japanese cinema to the Western parts of the globe.

Since its release Rashomon has been adapted as a Broadway play and even remade as a Western. Paving the way and inspiring Western films such as The Killing, Last Year at Marienbad and Four Times a Night; Made in the 50s, 60s and 70s. Even The Usual Suspects and Reservoir Dogs from present day Cinema have copied the narrative slant that Rashomon took many years before in 1950.

Often cited as the film that prompted The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences to create an award for Best Foreign Language film. It is widely regarded as a masterwork of world cinema.

Set in 12th Century Japan, the film's premise is at once both very simple yet very complicated.

The film depicts the rape of a woman and the murder of her samurai husband, through the widely differing accounts of four witnesses, including the bandit/rapist, the wife, the dead man speaking through a medium (Fumiko Honma), and lastly the narrator, the one witness that seems the most objective and least biased. Whilst the stories are mutually contradictory only the final version is unmotivated by other factors. Accepting the final version as the truth (the now common technique of film and TV of only explaining the truth last was not a universal approach at that time) explains why in each other version "the truth" was worse than admitting to the killing, and it is precisely this assessment which gives the film its power, and this theme which is echoed in other works.

The story unfolds in flashback as the four characters—the bandit Tajōmaru (Toshirō Mifune), the samurai's wife (Machiko Kyō), the murdered samurai (Masayuki Mori), and the nameless woodcutter (Takashi Shimura)—recount the events of one afternoon in a grove. The first three versions are told by the priest (Minoru Chiaki), who was present at the trial as a witness, having crossed paths with the couple on the road just prior to the events. Each of these versions has a response of "lies" from the woodcutter. The final version comes direct from the woodcutter, as the only witness (but he did not say this version to the court). All versions are told to a ribald commoner (Kichijiro Ueda) as they wait out a rainstorm in a ruined gatehouse identified by a sign as Rashōmon.

Rashomon has forever been among favourites of Kurosawa's directional works and it deserves every praise and Award acquired. Why? Simply because the story follows a unique narrative and story telling format never before seen at the time, in the World of Cinema.

During Akira's lifetime, he managed to confirm himself as one of the world's leading film-makers. A film maker whom created cinema which was impossible to compare, and his influence still resounds within even the most mainstream works from today. For example, the non-linear styling structure of Rashomon has been respectfully woven into numerous films since.

Kurosawa's admiration for silent film and modern art can be seen in the film's minimalist sets. Kurosawa felt that sound cinema multiplies the complexity of a film: "Cinematic sound is never merely accompaniment, never merely what the sound machine caught while you took the scene. Real sound does not merely add to the images, it multiplies it." Regarding Rashomon, Kurosawa said, "I like silent pictures and I always have ... I wanted to restore some of this beauty. I thought of it, I remember in this way: one of techniques of modern art is simplification, and that I must therefore simplify this film."

Accordingly, there are only three settings in the film: Rashōmon gate, the woods and the courtyard. The gate and the courtyard are very simply constructed and the woodland is real. This is partly due to the low budget that Kurosawa received from Daiei Studios.

''I'm the one who should be ashamed. I don't understand my own soul.''

Rashomon was the work which propelled the career of Kurosawa, even though it was not widely regarded in its own country at the time, it was hailed by the critics of the Western world as a definitive masterpiece.

Rashomon is the compressed story of an innocent woman's rape and her husband's murder, performed by a ruthless bandit (acted out by Kurosawa's long-time muse, Toshirô Mifune).

Even though the bandit is caught and consequently put on trial, the seemingly simple crime soon becomes questionably more complicated as it is recounted from four individually detached eye-witness perspectives. Posing many philosophical and debatable questions for the viewer, the picture asks which story is the one to believe, through -what was at the time and still remains- a highly stylized storytelling technique. Establishing a verdict upon the heinous crime in Rashomon is as much an ordeal as the crime itself because it proves to be an incident which provokes moral questioning and fierce debate.

The film-making techniques used in Rashomon gave birth to a distinctive style that Kurosawa was prepared to develop further in his later works, which can be seen in films such as Yojimbo and Shichinin no samurai.

Level-headed pragmatism plagued Kurosawa's features throughout his earlier years; This was something that came as an advantage for his films, being that the characters (even the bad) portrayed in his films were genuine people you could feel compassion and remorse for.

Also, Kurosawa began to define genres throughout the 1950s and 1960s, while also bringing to light some now-popular methods of camera movement, e.g. Dutch angles, revolving shots and amplified close-ups.

Symbolism also runs rampant throughout the film and much has been written purely revolving around this subject. Cinematographer Kazuo Miyagawa directly filmed the sun through the leaves of the trees, as if to show the light of truth becoming obscured. The gatehouse that we continually return to as the 'home' location for the storytelling serves as a visual metaphor for a gateway into the story, and the fact that the three men at the gate gradually tear it down and burn it as the stories are told is a further insight into the nature, concerning the truth of what they are telling.

For those who question the film's offbeat narrative structure, they should ask themselves whether or not the cut-throat editing is there as a means of symbolising the colliding viewpoints. I consider this to be a daring means of combining humanitarian lies and honesty, also resulting in a means of creating a disorientating, volatile impression upon film itself.

With Rashômon, Kurosawa's admiration for silent cinema is seen yet again; The minimalist set-pieces are a contrast to the complex storytelling procedure that his work embodies and captures. The ambiguity of Rashômon is detailed through subtly metaphorical cinematography and lighting techniques. The setting of the woods equalling a display of the work's central atmosphere (intrigue, depth) and the shadows periodically depicting a loss of empathy and symbolizing the isolated danger of the reflective surroundings.

Kurosawa's skill is not just restricted to dialogue and corresponding relationships; His visual acuity helps accentuate these themes. When the story begins, the woods is magical, it is alive and retaining intrigue. It is a woods of fairy tale proportions, with mystical breezes and tranquil streams.

As Rashomon progresses, the woods lose more and more of their mystical quality and become dirty, dry and ultimately real.

By the time the battle between the husband and the bandit is played out in a final representation, it is no longer a valiant battle of skill against two well-versed opponents, it is a stressful, scary affair that has the two kicking up more dust than swinging their blades. The dust itself shows the degradation of the story, that is Rashomon, coming away from the abstract qualities, qualities again attempting to grasp justice and truth.

If we accept the last version from The Woodcutter to be true we can assess what motivated each different story version regarding events that transpired. The truth appears to be a sorry but realistic state of affairs, filled with shame and cowardice. It must be remembered that all parties were present and all know the true sequence of events. There is therefore motivation behind each response.

In the bandit's version he accepts blame, but makes the fight appear an honourable and heroic battle. He therefore retains his reputation as a fierce and manly warrior.

In the wife's version, given that the truth lays alot of blame on her for inciting the duel, she has to appease for her actions. Morally she feels guilty for his death and so she accepts direct blame by saying she stabbed him.

The medium's version requires two interpretations: one if you accept that spirits can speak through a medium; a second if you presume it is the medium themselves giving this interpretation of events. If seen from the viewpoint of the now dead samurai, he has reason to be ashamed. Taking full blame for his own death, pardoning the bandit, and stating that his wife was largely to blame for the duel this is perhaps a fair approach. If we presume this version to be the invention of the medium, this interpretation has a slightly different slant (because they do not know the true events).

In this case, assembling information from the other witnesses paints a broad picture. Choosing a suicide option lays less blame on the two survivors and can be seen as a damage-limitation exercise.

However, the overall issue here is that one can be on a morally higher ground by admitting to a murder rather than admitting to other actual actions, and this is the revelation of the film.

Rashomon proves that truth lies with perspective. Lies can be used for selfish motivations yet also sometimes with good intentions; It teaches the treachery of humanity yet rekindles hope by the Woodcutter redeeming Man.

Did the Woodcutter steal the dagger from the murder scene? Maybe. Was it for selfish reasons? I don't believe so. The Commoner says all humanity is motivated by self interest and selfish impulses. Yet he is proved wrong.

The baby the three discover at the end prompts the priest and Woodcutter when alone together to reveal how selfless humanity can be. The woodcutter has six children, and despite all of this, he accepts the child as his own. So, if he did take the dagger it wasn't for selfish inclinations but to provide and care for his family. This reasserts glimmers of hope and redemption for humanity in the eyes of the priest and indeed audience.

''We all want to forget something, so we tell stories. It's easier that way.''

10/10

Login

Login