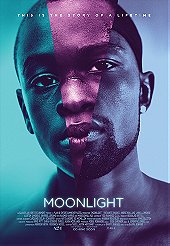

Moonlight is a prime example of the ephemeral and indefinable qualities of “it.” Here is a deeply personal story, sometimes achingly and uncomfortably so about one man’s defining and altering experiences across three different points. It’s just the personal empathy and emotional investment that Moonlight commands of us, but the vibrant direction of Barry Jenkins that makes this such a transforming cinematic experience. Moonlight is what I want more of cinema to aspire to be.

The narrative is fairly slight, but this is not a bad thing. So films are epic tomes of dense plotted incidence, and others are finely detailed character portraits. Moonlight is very much the latter with its trio of performances as the central character, Chiron. I’m not sure which one of the three actors inhabited the role first, but all three of them exhibit the same learned postures and expressive eyes. Chiron is a quiet character, deeply withdrawn and prone to moments of silence where we can only gauge his emotional reactions through the way his shoulders slump, or his eyes plead. This specificity of character is written into the narrative, and Chiron’s emotional and sexual awakenings feel like a lived in truth.

Even better is the ensemble of actors, led by the three people playing Chiron. Alex Hibbert is first as a shy kid, then Ashton Sanders as an awkward teenager, and finally Trevante Rhodes as a wounded adult. Hibbert gets the least amount of dialog and business to do, with much of his performance being merely reactive to the chaos surrounding him, but he’s a knockout. His face contains depths of pain and longing that only deepen the character as it’s passed along and the others borrow this body language. Sanders adds a simmering rage that threatens to explode into violence at any minute, and does as the second section wraps up. Then Rhodes adds more complexity to the character by turning these things into masks for a vulnerable core, and expressing a hesitancy that cracks apart his gruff exterior. He interacts with André Holland beautifully, but Rhodes’ best scene is quite possibly the reactive one where Naomie Harris’ mother apologizes for putting him through a never-ending series of horrors and he softly cries before telling her that she has his forgiveness.

Moonlight is made up of these kind of quiet interactions between characters, and several of them are haunting in how real they feel. Moonlight’s three section focus in on Chiron’s relationships with two people in his life: his abusive, drug-addicted mother (Naomie Harris) and school age friend Kevin (also played by three actors, but most effectively by André Holland as an adult). Many of the scenes involving Harris’ Paula struck something very deep within me, a sense of shared pain and history with this character that felt accurate in its small details. The glimpses of objects and interactions among adults that don’t make sense entirely to your youthful gaze, the sense of emotional indifference or downright hostility from a parent that is entirely misplaced on their part, the deep feeling of being collateral damage in their self-destruction. Moonlight was oddly a soulful affirmation of past traumas in giving life to these shared experiences between myself and Chiron. It was as if someone saw us and what we had endured.

Everyone speaks about Moonlight as a gay drama, and it is, make no mistake. But that tidily fits it into too specific a box, the same way that dubbing it a black or urban drama does as well. This is absolutely revolutionary for the simple fact that it gives voice and presence to queer people to often ignored by the wider media, but this is a towering achievement to the complexity of humanity. There’s no soothing balm here like there would be in something like The Help or Dallas Buyers Club, but there is a shared truth in Chiron’s quest for wholeness and to be seen. This is the type of film that I want to see sweep up Oscars by the armful. None of this is to argue that Moonlight’s blackness and queerness are inessential to the narrative, for they very much are, but an argument that someone who would potentially be wary of a film about those things should rethink that idiotic stance. Moonlight takes pieces of all of those film styles, and twist them around so that the souls of its characters are naked and porous for our understanding.

The greatness of Moonlight can be neatly traced to the final section’s long scene of re-connection between Kevin and Chiron. This is not an ending for either of them, but an arrival. After the heartbreak, anger, and pathos of the first two segments, this third one is a cleansing baptism and rebirth for both men. Chiron, in particular, finally begins stepping into his authentic self and emotional maturity, perhaps finally going about finally putting his emotional truths forward and gaining perspective on his wants and needs. This last section is also a marked departure from the rest of the film, which was kinetic and chaotic portraits of faces, lights, and music. This last section is more straightforward formalism with a pervading sense of calm, and this is necessary to really underscore the point of re-connection, forgiveness, and awakening.

Login

Login