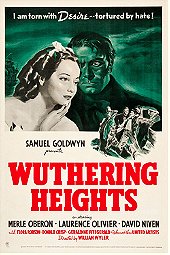

Any adaptation of Wuthering Heights that plays the central relationship between Heathcliff and Cathy as the pinnacle of romanticism is well lost. There’s nothing romantic about their abusive relationship, which spirals out into the succeeding generation in the novel’s second part. No great shock that William Wyler’s 1939 version drops the second half, improbably giving the duo a happily-ever-after in the afterlife, and plays out as the kind of stuffy, stagy studio era film-making that puts people off of these things.

Some of this goes back to the source material, Emily Bronte’s novel is un-adaptable, a long descent into repeating abuse patterns mistaken as romantic gestures. Heathcliff is obsessed with Cathy, mistaking the real person for the imagined creature he has crafted in his mind, while Cathy is an opportunist, a shape-shifting creature who promises domesticity to ensure marriage to a rich suitor, despite all of it being contrary to her true nature. They deserve a hellish reunion, one where they can reunite and cause havoc on everyone around them in a chamber of horrors. This is not romantic, but it sure is gothic.

Wyler misplaces the emphasis on the romance, and shortchanges us on the gothic. The tempestuous, often petty, dealings between Heathcliff, Cathy, and Hindley are played in strange keys. Hindley clearly translated from the page remains as an alcoholic brute, with Hugh Williams doing solid work in the thankless role, but the two leads are played as some kind of star-crossed lovers. Heathcliff is frequently cruel to Cathy, and she, in turn, brings others into their mess.

During production, Laurence Olivier and Merle Oberon famously detested each other. Olivier, looking impossibly handsome with facial scruff and pauper’s clothing, wanted Vivien Leigh to play opposite him, while Oberon was sad about leaving behind Alexander Korda, who she would soon go on to marry. Tension between co-stars can generate into erotic heat in some films, Veronica Lake and Fredric March sparred on I Married a Witch’s set and they charm together in the film. Olivier and Oberon never gel as a coupling, with Olivier unable to shake off his stage mannerisms and Oberon appearing indifferent to the part. She’s passive to the point where she seems to happily take the abuse thrown at her.

If the two leads are a wash, they’re at least surrounding by a parade of character actors who can reliably liven things up. Flora Robson, Donald Crisp, Leo G. Carroll, Cecil Kellaway all do work in various sized parts. David Niven and Geraldine Fitzgerald are solid as the Linton siblings, those poor souls who get tangled up in the deceitful web between Cathy and Heathcliff. Fitzgerald’s showcase scene, where she announces her intention to marry Heathcliff and proceeds to call Cathy out, outclasses anything that Oberon does in the film.

The dramatic emphasis may be all wrong in this, but it looks wondrous. Cinematographer Gregg Toland does great work here and deservedly won an Oscar for his expressive lighting. Toland seems to be the only person attuned to the gothic trappings of the source material. He makes the main houses look like torture chambers, vast tombs that ensnare the worst of human emotions. He goes a long way towards making the Californian coast look like the English moorlands.

Alfred Newman’s score is a major problem, though. It’s not bad, in fact, it’s quite good, swelling, romantic, and melodramatic, but it’s wrong for the material. It’s just another element of this film which misplaces the emphasis. Wuthering Heights is not a romantic story, but the heart-swelling strings played during the deathbed reunion of Cathy and Heathcliff play the scene as that, practically twisting your arm into reaching for a hankie.

Oh, that ending though, it practically torpedoes Wuthering Heights, which up to this point had been a solidly assembled if stuffy film. That ending is truly tone deaf, both for the material and the surrounding film. I’m not sure it’s one of the glossy standard bearers of 1939’s Golden Year musings, but it’s finely made if problematic. Watch for Toland’s deep focus camera work, Fitzgerald’s captivating performance, an assortment of solid supporting players, but be prepared for a lot of verbosity and hammy theatrics from the leads.

Login

Login