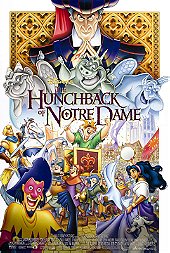

One of the strangest turns in the Renaissance found Disney crafting more substantive and emotionally mature works. You can see and feel the tension between the artists trying to expand what a Disney film could be, and the higher-ups demanding measures be taken to ensure a healthy chunk of merchandising profits. The Hunchback of Notre Dame suffered the worst from this tension.

Half of the film is a thoughtful, dark examination of religious hypocrisy, xenophobia, steeped in Catholic symbolism and a villain who is terrifying for being all too realistic. The other half is cutesy sidekicks cracking wise and making various pop culture references. It’s messy, but it’s grandly ambitious. I think it succeeds more than it fails, and its potential for greatness is evident, even if it is final form is muted and compromised.

There is no way to properly tell this story and include a happy ending for its main characters. Disney finds a way to include one, but it feels like a cheat. In fact, this ending, and the presence of the gargoyles as mere slapstick and comedic sidekicks, hinders the film each time it tries to soar. While the city of Paris is burning to the ground, Disney cheats the logical conclusion of the narrative and keeps everyone alive that is good, killing only the villain.

It’s easy moralizing from a film that so frequently skirts around it. Much of The Hunchback of Notre Dame takes a long, hard look at Judge Frollo’s religious hypocrisy, delivering a villainous character who is utterly frightening. Sure, one of Disney’s specialties is crafting memorable villains, but so many of them were entertaining in their outlandish scheming and grotesque behavior. Frollo is easily identifiable in our real world. A man who claims piety and deep religious belief while using it as a weapon against mass groups of people he deems unworthy, conflating his suppressed desires and lusts as witchcraft put upon him by a wicked female.

When The Hunchback of Notre Dame focuses in on the more realistic and disturbing aspects of the story, it never fails to impress. The backgrounds are a step above anything else in the Renaissance thus far. The cathedral faithfully represented, and the amount of detail staggering. By this point, Disney was pouring large amounts of money, time, and resources into its animation department. The character work is fluid and dynamic, and the various musical numbers gloriously rendered.

Three moments always manage to stick with me each time I view the film. “Out There,” Quasimodo’s heartfelt plea to join in with the rest of the world, to find a place of belonging, to connect with others, is a beautiful moment. “Topsy Turvy” a song explaining the day of celebration, and it’s an explosion of color, whimsy, and mirth-making. But the best moment in the entire film is “Hellfire,” Frollo’s condemnation of Esmeralda, his denial of his own lustful thoughts, and a conversation with his own suppressed guilt and thoughts. It’s the most mature musical number in the entire catalog of Disney films, rich with images of Catholic guilt and religious symbols. Disney hasn’t gone this dark and twisted, but loaded with hefty meaning since “Night on Bald Mountain” in Fantasia. I wonder if non-Catholics can appreciate it as much as this (heavily) lapsed one?

Not to say that the rest of the score isn’t phenomenal, because it is. Alan Menken and Stephen Schwartz dig deep in religious music for the score, as it is loaded with hymns, chants, and phrases lifted straight from a mass. “God Help the Outcasts,” a lovely prayer for the poor and downtrodden, sung by Esmerelda hammers in on the point the film is trying to make – we are all children of god, and we should look after each other, love one another. She clearly believes in a loving and forgiving god, reminding us that Jesus was an outcast in his time, and it is a beautiful sentiment.

But then there’s those damn gargoyles. I agree that Quasimodo needed characters to interact with, and the film briefly flirts with making the gargoyles figments of his imagination, as he has been kept isolated and emotionally abused his entire life. Yet, the film also wants the gargoyles to be real, and to be childish moments of levity. These moments puncture holes in the atmosphere and tone that the film had so consistently been working towards. If I could change one thing, I wouldn’t change the talking gargoyles, I wouldn’t even change using them as moments of levity, but I would change how they are used in these moments. Hearing Jason Alexander’s voice cracking post-modern jokes really takes you out of the moment.

And this points to a bigger problem within the Renaissance – the insistence on celebrity voices can occasionally take you out of the film. It was weird enough hearing Mel Gibson as an English settler in Pocahontas, but Demi Moore as the Romani Esmerelda is distracting. It doesn’t help that her vocal work is merely adequate. Jason Alexander, Mary Wickes, and Charles Kimbrough as the gargoyles are distracting to the point of consciously taking you out of the narrative momentum. Kevin Kline, Tom Hulce, Paul Kandel, and Tony Jay, especially, all do solid to great work in their respective roles.

Yes, it is WILDLY inconsistent in tone, but I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for The Hunchback of Notre Dame. I find it’s ambitious nature quite charming. I appreciate that it’s an American animated film that tried to push the art form away from just mindless family entertainments. It didn’t entirely succeed, but I think it’s an essential viewing experience for even daring to soar so high.

Login

Login