PopMatter's Essential Film Performances - 2013

Sort by:

Showing 50 items

Decade:

Rating:

List Type:

For this year’s annual update, we are abiding by the weird and wacky Hollywood Foreign Press guidelines for this historically-debatable category of Musical or Comedy, which has often included some eyebrow-raising choices that range from appropriate, inspired nominees and winners to head-scratchers that sorta make sense and to the utterly perplexing.

Julie Andrews

“A woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman?” Preposterous, except in Julie Andrews’ comedic hands. As down and out singer Victoria Grant in 1930’s Paris, Andrews delivers what is her best musical comedy performance. Transformed from the pitiful and weak wanna-be (best line: “I’ll sleep with you for a meatball.”) to the toast of gay Paree nightlife, Grant finds that her life grows increasingly more complicated as her attempts to deceive the world about who she truly is begin to unravel. Although easily dismissed as light-hearted comedy, Andrews’ performance is incredibly complex, requiring Andrews to assume multiple personas while still projecting the innocence and purity of the central character. Further, she has to keep up the façade while her character undergoes multiple changes in her life. Not only does the role require Andrews to show greater depth in her character development, it allows her to show a broader range in her musical repertoire than previous films had, including the Latin flavored “The Shady Dame of Seville” and the New Orleans influenced “Le Jazz Hot”, while still letting Andrews do the types of song she does best, with the ballad “Crazy World”.

The film also marks a resurgence for Andrews, reclaiming her status as Musical Royalty. After being the darling of ‘60s musicals, Andrews found her career in a slump when musicals stopped being big box office in the ‘70s. By aligning herself with her husband, director Blake Edwards, Andrews was able to reinvent herself, however, showing a more mature and worldly side of herself in films such as 10 and S. O. B., in which she bared more than just her worldly side, flashing her breasts to a shocked public. Edwards’ Victor/Victoria was her first musical in 12 years, and even then, all musical numbers were stage performances, not woven into plot development. Still, it’s evident that Andrews is grateful to be signing on screen again.

If singing was the easy part for Andrews, navigating the sexual politics within the film must have been the true work. Whether playing a woman, a woman pretending to be a man, or a woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman, Andrews is able to add sufficient layers to each characterization to make it unique. The film’s love story requires her to be both a woman in love in private and a man in a gay relationship in public. It all sounds terribly convoluted, and it is, but Andrews make every moment completely believable and wholly entertaining.

-Michael Abernethy

“A woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman?” Preposterous, except in Julie Andrews’ comedic hands. As down and out singer Victoria Grant in 1930’s Paris, Andrews delivers what is her best musical comedy performance. Transformed from the pitiful and weak wanna-be (best line: “I’ll sleep with you for a meatball.”) to the toast of gay Paree nightlife, Grant finds that her life grows increasingly more complicated as her attempts to deceive the world about who she truly is begin to unravel. Although easily dismissed as light-hearted comedy, Andrews’ performance is incredibly complex, requiring Andrews to assume multiple personas while still projecting the innocence and purity of the central character. Further, she has to keep up the façade while her character undergoes multiple changes in her life. Not only does the role require Andrews to show greater depth in her character development, it allows her to show a broader range in her musical repertoire than previous films had, including the Latin flavored “The Shady Dame of Seville” and the New Orleans influenced “Le Jazz Hot”, while still letting Andrews do the types of song she does best, with the ballad “Crazy World”.

The film also marks a resurgence for Andrews, reclaiming her status as Musical Royalty. After being the darling of ‘60s musicals, Andrews found her career in a slump when musicals stopped being big box office in the ‘70s. By aligning herself with her husband, director Blake Edwards, Andrews was able to reinvent herself, however, showing a more mature and worldly side of herself in films such as 10 and S. O. B., in which she bared more than just her worldly side, flashing her breasts to a shocked public. Edwards’ Victor/Victoria was her first musical in 12 years, and even then, all musical numbers were stage performances, not woven into plot development. Still, it’s evident that Andrews is grateful to be signing on screen again.

If singing was the easy part for Andrews, navigating the sexual politics within the film must have been the true work. Whether playing a woman, a woman pretending to be a man, or a woman pretending to be a man pretending to be a woman, Andrews is able to add sufficient layers to each characterization to make it unique. The film’s love story requires her to be both a woman in love in private and a man in a gay relationship in public. It all sounds terribly convoluted, and it is, but Andrews make every moment completely believable and wholly entertaining.

-Michael Abernethy

JxSxPx's rating:

Ann-Margret

Throughout the ‘50s and early ‘60s, this Swedish born singer and performer was seen as the stuff of glitzy, superficial Las Vegas show business, a kitten with a whip who made the King sing “Viva” whenever he thought of Sin City. If there was such a thing as a female teen idol, she was one. Her entire professional demeanor, polished by handlers who knew how potent her sex appeal could be, was based around hip hugging pants, suggestive dance moves, and a personality that practically shouted sensuality. As the Peace Decade progressed, however, Ann-Margret (it’s one name, thank you very much) wanted to be taken more seriously. She was through with such shallow onscreen roles as Kim in Bye, Bye Birdie. Then, in 1971, she costarred alongside Jack Nicolson, Art Garfunkel, and Candice Bergen in Mike Nichol’s controversial Carnal Knowledge and the Academy Awards came calling (with a Best Supporting Actress nomination).

From there, she struggled to find roles that downplayed her pin-up good looks. In 1972, a fall from an elevated stage platform left her with a broken arm, shattered cheekbone and jaw. It took meticulous cosmetic surgery to rebuild Ann-Margret’s damaged face, and by 1975, she was ready to prove her musical mettle again. In one of Ken Russell’s characteristically odd casting decisions, he made this glamour gal the worn out, workaday mum to Roger Daltry’s deaf, dumb, and blind boy Tommy, and the rest is rock opera history. Oscar once again couldn’t ignore her near nuclear performance (another nomination, this time for Best Actress) while the Golden Globes gave her their highest honor. Watching the film, it’s easy to see why. Everything the sexpot firebrand brought to her previous personas was encapsulated in a woman who, after psychologically damaging her impressionable child, spends the rest of the story trying to right a repugnant wrong.

While others in the cast had the more memorable tunes from Pete Townshend’s groundbreaking album, Ann-Margret became the glue that held it all together. While Tina Turner was screeching about her “Acid Queen” royalty and Who drummer Keith Moon played a lovable old pervert, the blond bombshell literally exploded across the screen, offering up a range of emotions that few could fathom artistically, let alone sing about with abject conviction. But Ann-Margret made it look easy, even if she was rolling around in a pool of chocolate pudding and baked beans (don’t ask, it’s Ken Russell). By then end, when she’s traded her role as a murderess (or co-conspirator for same) for high society mother of the post-modern messiah, her work came full circle… almost meta. Everything Ann-Margret struggled to escape from during the previous decades finally catches up with her character in the film, turning a standard leading lady role into the stuff of movie myth. It’s an amazing turn from an equally astonishing show biz survivor.

-Bill Gibron

Throughout the ‘50s and early ‘60s, this Swedish born singer and performer was seen as the stuff of glitzy, superficial Las Vegas show business, a kitten with a whip who made the King sing “Viva” whenever he thought of Sin City. If there was such a thing as a female teen idol, she was one. Her entire professional demeanor, polished by handlers who knew how potent her sex appeal could be, was based around hip hugging pants, suggestive dance moves, and a personality that practically shouted sensuality. As the Peace Decade progressed, however, Ann-Margret (it’s one name, thank you very much) wanted to be taken more seriously. She was through with such shallow onscreen roles as Kim in Bye, Bye Birdie. Then, in 1971, she costarred alongside Jack Nicolson, Art Garfunkel, and Candice Bergen in Mike Nichol’s controversial Carnal Knowledge and the Academy Awards came calling (with a Best Supporting Actress nomination).

From there, she struggled to find roles that downplayed her pin-up good looks. In 1972, a fall from an elevated stage platform left her with a broken arm, shattered cheekbone and jaw. It took meticulous cosmetic surgery to rebuild Ann-Margret’s damaged face, and by 1975, she was ready to prove her musical mettle again. In one of Ken Russell’s characteristically odd casting decisions, he made this glamour gal the worn out, workaday mum to Roger Daltry’s deaf, dumb, and blind boy Tommy, and the rest is rock opera history. Oscar once again couldn’t ignore her near nuclear performance (another nomination, this time for Best Actress) while the Golden Globes gave her their highest honor. Watching the film, it’s easy to see why. Everything the sexpot firebrand brought to her previous personas was encapsulated in a woman who, after psychologically damaging her impressionable child, spends the rest of the story trying to right a repugnant wrong.

While others in the cast had the more memorable tunes from Pete Townshend’s groundbreaking album, Ann-Margret became the glue that held it all together. While Tina Turner was screeching about her “Acid Queen” royalty and Who drummer Keith Moon played a lovable old pervert, the blond bombshell literally exploded across the screen, offering up a range of emotions that few could fathom artistically, let alone sing about with abject conviction. But Ann-Margret made it look easy, even if she was rolling around in a pool of chocolate pudding and baked beans (don’t ask, it’s Ken Russell). By then end, when she’s traded her role as a murderess (or co-conspirator for same) for high society mother of the post-modern messiah, her work came full circle… almost meta. Everything Ann-Margret struggled to escape from during the previous decades finally catches up with her character in the film, turning a standard leading lady role into the stuff of movie myth. It’s an amazing turn from an equally astonishing show biz survivor.

-Bill Gibron

JxSxPx's rating:

Beatrice Arthur

Decked out in a severe, black pageboy wig, martini glass firmly in-hand, Bea Arthur utters a singular, monosyllabic “yes” as her first line as Vera Charles in Mame, setting the tone for a memorable performance in an otherwise cringe-worthy film. It’s not hard for Bea Arthur to shine, even when thrown into what she herself dubbed “a disaster”. Yet, Arthur managed to turn in a dynamo performance, reprising the role that earned her a 1966 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Musical. Although she smelled a dud a mile away, the actress took part in the film adaptation of Mame to work alongside her husband, director Gene Saks.

While the 1974 film adaptation featured two of the same supporting actresses as the Broadway musical (Arthur and Jane Connell), Lucille Ball replaced Broadway star Angela Lansbury in the lead role since Warner Bros. felt that Lansbury would not be as big a box office draw. As aging boozehound / “First lady of the American theater” Vera Charles, Arthur plays best friend to Lucy’s Mame. Her grande dame of a character is often the butt of jokes and jabs at the hands of (in this instance, a fairly unlikeable) Mame, yet, the role of Vera gives Arthur a chance to not only deliver not only biting one-liners, but some of her patented reactions.

Comedy as an art form requires not just impeccable timing with delivering a line, but also calls for an actor to react to the delivery of his or her cohorts. It’s not just standing around, waiting to toss out your line and garner laughs. Comedians of the highest order know when to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em. As Vera, Bea Arthur demonstrates her formidable comedic prowess, using her height and deep voice to great effect, along with an expertly raised eyebrow and a sustained, withering glance that could flatten not just the village idiot, but the entire village in a single take.

Fans of Arthur who know her primarily through her work on sitcoms Maude and The Golden Girls are afforded a glimpse of her singing chops in two of the film’s numbers. Her rendition of “The Man in the Moon”, which features Vera-as-a-Lady-Astronomer in one of her (destined to flop) stage plays, sees Arthur somehow managing to create a dignified form of slapstick.

The second production number, “Bosom Buddies”, is a frenemy-themed duet featuring Vera and Mame. In it, the two now-middle-aged friends celebrate their decades-long friendship and their ability to speak with catty candor to one another since, that’s what real friends do. The song is easily a highlight of the film and Arthur more than capably holds her own, even managing to steal the scene from the great Ball herself. Arthur’s singing voice is equally as expressive as her speaking voice, modulating her pitches to sound bright and chipper before dealing a crusher of a basso blow.

-Lana Cooper

Decked out in a severe, black pageboy wig, martini glass firmly in-hand, Bea Arthur utters a singular, monosyllabic “yes” as her first line as Vera Charles in Mame, setting the tone for a memorable performance in an otherwise cringe-worthy film. It’s not hard for Bea Arthur to shine, even when thrown into what she herself dubbed “a disaster”. Yet, Arthur managed to turn in a dynamo performance, reprising the role that earned her a 1966 Tony Award for Best Featured Actress in a Musical. Although she smelled a dud a mile away, the actress took part in the film adaptation of Mame to work alongside her husband, director Gene Saks.

While the 1974 film adaptation featured two of the same supporting actresses as the Broadway musical (Arthur and Jane Connell), Lucille Ball replaced Broadway star Angela Lansbury in the lead role since Warner Bros. felt that Lansbury would not be as big a box office draw. As aging boozehound / “First lady of the American theater” Vera Charles, Arthur plays best friend to Lucy’s Mame. Her grande dame of a character is often the butt of jokes and jabs at the hands of (in this instance, a fairly unlikeable) Mame, yet, the role of Vera gives Arthur a chance to not only deliver not only biting one-liners, but some of her patented reactions.

Comedy as an art form requires not just impeccable timing with delivering a line, but also calls for an actor to react to the delivery of his or her cohorts. It’s not just standing around, waiting to toss out your line and garner laughs. Comedians of the highest order know when to hold ‘em and when to fold ‘em. As Vera, Bea Arthur demonstrates her formidable comedic prowess, using her height and deep voice to great effect, along with an expertly raised eyebrow and a sustained, withering glance that could flatten not just the village idiot, but the entire village in a single take.

Fans of Arthur who know her primarily through her work on sitcoms Maude and The Golden Girls are afforded a glimpse of her singing chops in two of the film’s numbers. Her rendition of “The Man in the Moon”, which features Vera-as-a-Lady-Astronomer in one of her (destined to flop) stage plays, sees Arthur somehow managing to create a dignified form of slapstick.

The second production number, “Bosom Buddies”, is a frenemy-themed duet featuring Vera and Mame. In it, the two now-middle-aged friends celebrate their decades-long friendship and their ability to speak with catty candor to one another since, that’s what real friends do. The song is easily a highlight of the film and Arthur more than capably holds her own, even managing to steal the scene from the great Ball herself. Arthur’s singing voice is equally as expressive as her speaking voice, modulating her pitches to sound bright and chipper before dealing a crusher of a basso blow.

-Lana Cooper

JxSxPx's rating:

Royal Wedding (1951)

Fred Astaire

One could pick just about any Fred Astaire performance and make a valid argument that it is his best, because, frankly, Astaire plays Astaire in just about every film: dashing, sophisticated, witty, sly, and good-natured. Yet, Royal Wedding presents Astaire in the many roles he took on in film—the debonair suitor, in this case for Sarah Churchill; the family man, protecting and battling with little sister Jane Powell; and master showman, performing as part of a brother—sister act in London for the royal wedding of Princess (now Queen) Elizabeth. The film’s plot is predictable and forgettable, but Astaire is at his absolute best. Even as we watch him deal with the inevitable obstacles he encounters both personally and professionally, we know that the big show will go off flawlessly and Astaire will get the girl of his dreams. What’s more, he will be his charming, joking self throughout highs and lows.

Beyond showing Astaire’s considerable charm at its best, Royal Wedding features three of Astaire’s—and film’s—greatest musical numbers. The most famous of these, “You’re All the World to Me”, finds Astaire alone in his hotel room, dancing his way around the entire room, including up the walls and across the ceiling, in celebration of his new love. Astaire first mentioned the idea for the scene in 1945, but it took him six years to actually capture it on film. The camera work is standard now, but it was revolutionary at the time and astounded audiences. Although this sequence is the film’s most often mentioned, it is not the film’s only memorable one. “Summer Jumps” finds Astaire alone on stage; lacking a partner (his sister has failed to show up for rehearsal), Astaire improvises, grabbing a hat stand and making it his dance partner. The scene seems to pay homage to rival Gene Kelly, mirroring Kelly’s “You, Wonderful You” number from Summer Stock the previous year. Equally good is Astaire’s number with Powell, “How Could You Believe Me When I Said I Love You When You Know I’ve been a Liar All My Life.” Here, Astaire is at his most playful, as a small-time thug trying to brush off some clingy dame. With Astaire in nipple-high pants and Powell smacking gum, the duo is in perfect sync in a dance that is equal parts contemporary dance, tap, and slapstick. This is the Astaire film-goers came to love—spirited but graceful. Even if Fred Astaire was playing the same character that he played in most of his films, no one could have played it like him.

-MA

One could pick just about any Fred Astaire performance and make a valid argument that it is his best, because, frankly, Astaire plays Astaire in just about every film: dashing, sophisticated, witty, sly, and good-natured. Yet, Royal Wedding presents Astaire in the many roles he took on in film—the debonair suitor, in this case for Sarah Churchill; the family man, protecting and battling with little sister Jane Powell; and master showman, performing as part of a brother—sister act in London for the royal wedding of Princess (now Queen) Elizabeth. The film’s plot is predictable and forgettable, but Astaire is at his absolute best. Even as we watch him deal with the inevitable obstacles he encounters both personally and professionally, we know that the big show will go off flawlessly and Astaire will get the girl of his dreams. What’s more, he will be his charming, joking self throughout highs and lows.

Beyond showing Astaire’s considerable charm at its best, Royal Wedding features three of Astaire’s—and film’s—greatest musical numbers. The most famous of these, “You’re All the World to Me”, finds Astaire alone in his hotel room, dancing his way around the entire room, including up the walls and across the ceiling, in celebration of his new love. Astaire first mentioned the idea for the scene in 1945, but it took him six years to actually capture it on film. The camera work is standard now, but it was revolutionary at the time and astounded audiences. Although this sequence is the film’s most often mentioned, it is not the film’s only memorable one. “Summer Jumps” finds Astaire alone on stage; lacking a partner (his sister has failed to show up for rehearsal), Astaire improvises, grabbing a hat stand and making it his dance partner. The scene seems to pay homage to rival Gene Kelly, mirroring Kelly’s “You, Wonderful You” number from Summer Stock the previous year. Equally good is Astaire’s number with Powell, “How Could You Believe Me When I Said I Love You When You Know I’ve been a Liar All My Life.” Here, Astaire is at his most playful, as a small-time thug trying to brush off some clingy dame. With Astaire in nipple-high pants and Powell smacking gum, the duo is in perfect sync in a dance that is equal parts contemporary dance, tap, and slapstick. This is the Astaire film-goers came to love—spirited but graceful. Even if Fred Astaire was playing the same character that he played in most of his films, no one could have played it like him.

-MA

JxSxPx's rating:

Billy Elliot (2000)

Jamie Bell

When a film features a young boy (Bell) cowering in the loo as he watches his father take an axe to the family piano to make much-needed firewood, it’s hard to imagine such a film is a musical or a comedy. Granted, there is music and dancing—lots of dancing—but at its core, Billy Elliot is a family drama, focusing on how one father and son deal with gender expectations amidst a labor dispute and growing poverty. An Andy Hardy feel-good movie it isn’t, but then, Jamie Bell is no Mickey Rooney. In Billy Elliot, Bell is brooding, intense, talented, intelligent, inquisitive, frightened, and utterly compelling; consequently, he found himself at the age of 14 as BAFTA’s youngest Best Actor winner and a SAG nominee.

Billy Elliot likes to dance, causing him to abandon the boxing class his father wants him in for the dance classes taught in the same gym. Set against the mining labor strikes of 1984, the film concerns itself with what it means to be a man—does it mean standing up for what you believe or swallowing your pride to support your family? Is it pursuing what is manly or chasing after what you love to do, even if the world may not approve? Even as Billy struggles with the latter question, his father struggles with the former, setting up a clash of identities. At the core of all these struggles is Bell, carefully weaving between the competing forces in Billy’s world, serving as silent observer, absorbing the conflicts and channeling it all into his dance. The film’s highlight number finds Bell dancing through the streets of his town to the Jam’s “A Town Called Malice”, full into his rage after a fight between his father and dance teacher. Bell’s every movement as he dances screams the words he cannot say. The dance perfectly sets up the scene’s pivotal scene, and Bell’s most moving, as Billy explains what it feels like to dance in front of a dance academy audition panel. There is a clarity and maturity in Bell’s delivery that exceeds his age, plus the kid can dance like hell. Whether engaging in a playful dance with his teacher, the delightful Julie Walters, or proving his love of dance to his father, Bell is a joy to watch.

-MA

When a film features a young boy (Bell) cowering in the loo as he watches his father take an axe to the family piano to make much-needed firewood, it’s hard to imagine such a film is a musical or a comedy. Granted, there is music and dancing—lots of dancing—but at its core, Billy Elliot is a family drama, focusing on how one father and son deal with gender expectations amidst a labor dispute and growing poverty. An Andy Hardy feel-good movie it isn’t, but then, Jamie Bell is no Mickey Rooney. In Billy Elliot, Bell is brooding, intense, talented, intelligent, inquisitive, frightened, and utterly compelling; consequently, he found himself at the age of 14 as BAFTA’s youngest Best Actor winner and a SAG nominee.

Billy Elliot likes to dance, causing him to abandon the boxing class his father wants him in for the dance classes taught in the same gym. Set against the mining labor strikes of 1984, the film concerns itself with what it means to be a man—does it mean standing up for what you believe or swallowing your pride to support your family? Is it pursuing what is manly or chasing after what you love to do, even if the world may not approve? Even as Billy struggles with the latter question, his father struggles with the former, setting up a clash of identities. At the core of all these struggles is Bell, carefully weaving between the competing forces in Billy’s world, serving as silent observer, absorbing the conflicts and channeling it all into his dance. The film’s highlight number finds Bell dancing through the streets of his town to the Jam’s “A Town Called Malice”, full into his rage after a fight between his father and dance teacher. Bell’s every movement as he dances screams the words he cannot say. The dance perfectly sets up the scene’s pivotal scene, and Bell’s most moving, as Billy explains what it feels like to dance in front of a dance academy audition panel. There is a clarity and maturity in Bell’s delivery that exceeds his age, plus the kid can dance like hell. Whether engaging in a playful dance with his teacher, the delightful Julie Walters, or proving his love of dance to his father, Bell is a joy to watch.

-MA

JxSxPx's rating:

Dancer in the Dark (2000)

Björk

“I’ve seen it all, I have seen the dark, I have seen the brightness in one little spark. I’ve seen what I was and I know I what I’ll be, I’ve seen it all, there is no more to see…” So goes the Oscar-nominated tune written (improbably) by singer-composer Björk and her director Lars Von Trier, evoking the film’s undeniably powerful, melodramatic underpinnings which play out on screen like some mad cinematic hybrid of Douglas Sirk and the Fred Astaire/Cy Charisse musical The Band Wagon (1953). With Von Trier trying on his Minnelli hat, additionally, the spectator is treated to Björk doing her best riff on Giulietta Masina, part child-clown drowning in a well of sadness, part dimunitve dynamo full of pluck and strength; a thoroughly complex creation given the leading lady’s complete lack of experience in acting for the screen.

As Selma, an immigrant single mother living with her teenage son in the 1960s, Björk gives in an impeccably modulated performance made up of such astonishing, seamless details that she not only that grounds the director’s implausible (if brilliant) melodrama in reality, but in fact deep within in the beating heart. Selma’s only reason for living, for toiling away in a back-breaking, dangerous factory job as her eyesight becomes worse and worse, is to save her son from the same hereditary disease by wheedling away every penny to pay for his operation. A Czech woman barely getting by who came searching for the American dream, who daydreams of starring in splashy American musicals, Selma’s only pleasures in life become her undoing as a series of horrible circumstances conspire to land her on trial for murder and finally on death row. In these later scenes, a few of which are shared with the legendary Catherine Denueve to tremendous effect, Björk does the impossible: she makes you forget you are watching Björk.

These moments that find Selma going through a xenophobic, unfair judicial system, crackle with dramatic intensity. As a singer, the command Björk has over the vocal elements of the character—not just the singing, but the powerful attention to every word Selma says and how she says them—is beautiful. Though, to those of us who know her live show well it comes as no revelation that Björk, who once sang so poignantly about feeling “emotional landscapes” on Homogenic, could feel her way into a character through creating just that: the “emotional landscape” through creating a voice for a woman she might not have a lot in common with, but that she can connect with on a divinely synergistic plane through her compositions and singing. Yes, it is sad she won’t take another acting role (though she did appear in Matthew Barney’s Drawing Restraint 9), but the strength of her tour performances continues to impress, and to be fair, most of those could stand up against almost any film performance on this list, if we’re really talking “Essential Performances”.

-Matt Mazur

“I’ve seen it all, I have seen the dark, I have seen the brightness in one little spark. I’ve seen what I was and I know I what I’ll be, I’ve seen it all, there is no more to see…” So goes the Oscar-nominated tune written (improbably) by singer-composer Björk and her director Lars Von Trier, evoking the film’s undeniably powerful, melodramatic underpinnings which play out on screen like some mad cinematic hybrid of Douglas Sirk and the Fred Astaire/Cy Charisse musical The Band Wagon (1953). With Von Trier trying on his Minnelli hat, additionally, the spectator is treated to Björk doing her best riff on Giulietta Masina, part child-clown drowning in a well of sadness, part dimunitve dynamo full of pluck and strength; a thoroughly complex creation given the leading lady’s complete lack of experience in acting for the screen.

As Selma, an immigrant single mother living with her teenage son in the 1960s, Björk gives in an impeccably modulated performance made up of such astonishing, seamless details that she not only that grounds the director’s implausible (if brilliant) melodrama in reality, but in fact deep within in the beating heart. Selma’s only reason for living, for toiling away in a back-breaking, dangerous factory job as her eyesight becomes worse and worse, is to save her son from the same hereditary disease by wheedling away every penny to pay for his operation. A Czech woman barely getting by who came searching for the American dream, who daydreams of starring in splashy American musicals, Selma’s only pleasures in life become her undoing as a series of horrible circumstances conspire to land her on trial for murder and finally on death row. In these later scenes, a few of which are shared with the legendary Catherine Denueve to tremendous effect, Björk does the impossible: she makes you forget you are watching Björk.

These moments that find Selma going through a xenophobic, unfair judicial system, crackle with dramatic intensity. As a singer, the command Björk has over the vocal elements of the character—not just the singing, but the powerful attention to every word Selma says and how she says them—is beautiful. Though, to those of us who know her live show well it comes as no revelation that Björk, who once sang so poignantly about feeling “emotional landscapes” on Homogenic, could feel her way into a character through creating just that: the “emotional landscape” through creating a voice for a woman she might not have a lot in common with, but that she can connect with on a divinely synergistic plane through her compositions and singing. Yes, it is sad she won’t take another acting role (though she did appear in Matthew Barney’s Drawing Restraint 9), but the strength of her tour performances continues to impress, and to be fair, most of those could stand up against almost any film performance on this list, if we’re really talking “Essential Performances”.

-Matt Mazur

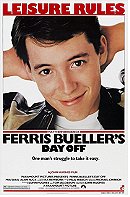

Ferris Bueller's Day Off (1986)

Matthew Broderick

Casting was absolutely crucial here. Had high school auteur Hughes stuck us with a generic Hollywood hunk in the role of the school-skipping, fourth-wall-breaking title character, Ferris Bueller might have been unbearably unctuous and obnoxiously entitled, particularly coming, as the film does, from the upper middle class milieu that Hughes’ typical setting. Because the filmmaker regarded ‘80s suburban America with equal parts sympathy and satire, though, he knew better than to alienate even his only slightly less privileged viewers (the ones who may be without either car or computer), and with the choice down to John Cusack (who would land his own definitive ‘80s teen role three years later as Say Anything‘s Lloyd Dobler) and Matthew Broderick, Hughes still wound up with the best possible Ferris.

Importing some of the cocky insouciance that the actor previously displayed as another computer wiz kid in John Badham’s WarGames (1983), Broderick plays Ferris as an impish every-teen, a hilarious literalization of David Elkind’s “personal fable”—note how the entire city of Chicago seems to rally together to “Save Ferris”—locating a quality essential in establishing his easy, witty rapport with the audience. Through Broderick’s winsome performance, we are invited along on his wish-fulfillment fantasy rather than passively observing it, and his (and Hughes’) balance of heart (as the motivation behind the day off is revealed as a last-ditch opportunity to win his hopelessly neurotic best friend some confidence and self-respect) and appealingly good natured sense of comic anarchy keeps the film as emotionally grounded as it is delightfully absurd. In a film rich with beautifully realized comic performances, from Alan Ruck, Mia Sara, Jennifer Grey, Jeffrey Jones and Edie McClurg in note-perfect supporting turns to Ben Stein and Charlie Sheen in brilliantly typecast cameos, Broderick remains both focal point and anchor, ensuring us that even if we are in no position to take a “day off” of our own, joining in on his remains a delightful alternative.

-Jer Fairall

Casting was absolutely crucial here. Had high school auteur Hughes stuck us with a generic Hollywood hunk in the role of the school-skipping, fourth-wall-breaking title character, Ferris Bueller might have been unbearably unctuous and obnoxiously entitled, particularly coming, as the film does, from the upper middle class milieu that Hughes’ typical setting. Because the filmmaker regarded ‘80s suburban America with equal parts sympathy and satire, though, he knew better than to alienate even his only slightly less privileged viewers (the ones who may be without either car or computer), and with the choice down to John Cusack (who would land his own definitive ‘80s teen role three years later as Say Anything‘s Lloyd Dobler) and Matthew Broderick, Hughes still wound up with the best possible Ferris.

Importing some of the cocky insouciance that the actor previously displayed as another computer wiz kid in John Badham’s WarGames (1983), Broderick plays Ferris as an impish every-teen, a hilarious literalization of David Elkind’s “personal fable”—note how the entire city of Chicago seems to rally together to “Save Ferris”—locating a quality essential in establishing his easy, witty rapport with the audience. Through Broderick’s winsome performance, we are invited along on his wish-fulfillment fantasy rather than passively observing it, and his (and Hughes’) balance of heart (as the motivation behind the day off is revealed as a last-ditch opportunity to win his hopelessly neurotic best friend some confidence and self-respect) and appealingly good natured sense of comic anarchy keeps the film as emotionally grounded as it is delightfully absurd. In a film rich with beautifully realized comic performances, from Alan Ruck, Mia Sara, Jennifer Grey, Jeffrey Jones and Edie McClurg in note-perfect supporting turns to Ben Stein and Charlie Sheen in brilliantly typecast cameos, Broderick remains both focal point and anchor, ensuring us that even if we are in no position to take a “day off” of our own, joining in on his remains a delightful alternative.

-Jer Fairall

JxSxPx's rating:

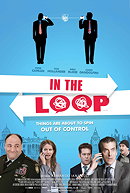

In the Loop (2009)

Pete Capaldi

The cursing in In the Loop, a film about the madcap escalation of a questionable remark made by International Development Minister Simon Foster (played by Tom Hollander), is so fast-paced that it becomes awe-inspiring. In director Armando Ianucci’s universe—which includes In the Loop‘s Britcom predecessor The Thick of It and the HBO hit Veep—no one is more eloquent in their profanity than Minister of Communications Malcolm Tucker. The controlled lunacy and ribald rage which Peter Capaldi brings to the role marks Tucker as one of the most threateningly hilarious creations of recent modern cinema.

Whether using two cell phones to berate two different people at the same time or administering such advice as “you stay detached, otherwise that’s what I’ll do to your retinas”, Malcolm Tucker is a fully realized nightmare of a work colleague. Originally thought to be inspired by British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Director of Communications, Alistair Campbell, the Scottish Capaldi has been quoted as saying that inspiration was also culled from Hollywood agents shouting into phones and Miramax Head Harvey Weinstein. Capaldi is never overused in In the Loop, and much of his performance does involve viciously conducting business by phone. A significant portion of the film’s opening scene involves Tucker traversing from 10 Downing Street to Simon Foster’s office while going into damage control mode over a major gaffe Foster made.

Another great asset of Tucker’s is his way with pop culture-related insults. One of the film’s most famous lines, “You sounded like a Nazi Julie Andrews” (told to Foster after he makes another press faux pas involving the phrase, “climbing the mountain of conflict”) is delivered by him. He continually calls Foster’s new aide Toby Wright (Chris Addison) such cruel nicknames as “Ron Weasly” and “the baby from Eraserhead.” And, of course, the use of the word “purview” provokes Tucker into making an obscene Jane Austen reference.

In a movie about communication, Tucker’s mode is actually most successful. He is one of the few characters who means what he says and gets the job done in doing so. Of all the people Tucker does business with, he meets his match but once, in an epic verbal face-off with the late, great James Gandolfini’s pacifist lieutenant general, George Miller. In a scene that fans of the film counted as a highlight even before Gandolfini’s passing, Tucker still gets the last word.

-Maria Schurr

The cursing in In the Loop, a film about the madcap escalation of a questionable remark made by International Development Minister Simon Foster (played by Tom Hollander), is so fast-paced that it becomes awe-inspiring. In director Armando Ianucci’s universe—which includes In the Loop‘s Britcom predecessor The Thick of It and the HBO hit Veep—no one is more eloquent in their profanity than Minister of Communications Malcolm Tucker. The controlled lunacy and ribald rage which Peter Capaldi brings to the role marks Tucker as one of the most threateningly hilarious creations of recent modern cinema.

Whether using two cell phones to berate two different people at the same time or administering such advice as “you stay detached, otherwise that’s what I’ll do to your retinas”, Malcolm Tucker is a fully realized nightmare of a work colleague. Originally thought to be inspired by British Prime Minister Tony Blair’s Director of Communications, Alistair Campbell, the Scottish Capaldi has been quoted as saying that inspiration was also culled from Hollywood agents shouting into phones and Miramax Head Harvey Weinstein. Capaldi is never overused in In the Loop, and much of his performance does involve viciously conducting business by phone. A significant portion of the film’s opening scene involves Tucker traversing from 10 Downing Street to Simon Foster’s office while going into damage control mode over a major gaffe Foster made.

Another great asset of Tucker’s is his way with pop culture-related insults. One of the film’s most famous lines, “You sounded like a Nazi Julie Andrews” (told to Foster after he makes another press faux pas involving the phrase, “climbing the mountain of conflict”) is delivered by him. He continually calls Foster’s new aide Toby Wright (Chris Addison) such cruel nicknames as “Ron Weasly” and “the baby from Eraserhead.” And, of course, the use of the word “purview” provokes Tucker into making an obscene Jane Austen reference.

In a movie about communication, Tucker’s mode is actually most successful. He is one of the few characters who means what he says and gets the job done in doing so. Of all the people Tucker does business with, he meets his match but once, in an epic verbal face-off with the late, great James Gandolfini’s pacifist lieutenant general, George Miller. In a scene that fans of the film counted as a highlight even before Gandolfini’s passing, Tucker still gets the last word.

-Maria Schurr

JxSxPx's rating:

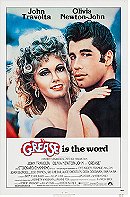

Grease (1978)

Stockard Channing

Usually when people think of Grease, flashbacks of Frankie Avalon serenading a pink-haired Didi Conn in the iconic “Beauty School Dropout” scene come to mind. Or John Travolta dancing on the hood of a Ford 1948 with his pals, belting out “Greased Lightning”. Or even Travolta and a leather-clad Olivia Newton-John’s epic final song and dance number, “We Go Together”. But many overlook the smaller yet significant portrayal of rebel leader Rizzo by Stockard Channing. In a performance that epitomized the girl power movement before it became a much talked about thing, Channing infused both sensitivity and toughness in a character that we loved to hate (or was it hate to love?).

When we first meet Rizzo, she’s sashaying onto the campus decked in skin-tight all-black attire with her two besties on the first day of school. With one quick summation of the scene, she deems it mildly worth her presence, and declares “We’re gonna rule the school.” Even just knowing her for all of a few minutes, we don’t have a doubt in our minds that she will. With just one look, Channing seduces audiences with an alluring combination of intimidation and curiosity. While she’s not what you’d call approachable, there’s something about her assuredness and femme fatale-ness that makes you yearn for the camera to stay on her. Channing makes sure that Rizzo isn’t just the naughty head bitch of the crew; the nuance she brings is measured down to the last drop.

We later learn that while Rizzo has the attention of both gals and gents, she secretly faces the risk of an unplanned pregnancy. Though the movie doesn’t spend many scenes on this, it is Channing who creates a bold moment with an affective rendition of “There Are Worse Things I Can Do”. The song, which even by itself has an empowered message, is further punctuated by the confidence and directness of Channing’s lyrical middle figure response to the gossipers and naysayers who’d undoubtedly brand her. It was a poignant reaction that only Rizzo could convey, as embodied by the remarkable Channing.

Channing took what could have been seen as a typical “mean girl” role and turned Rizzo into an indelible character we can all look up to, one that was made up more than just snarls and pouty lip gloss. She made her one of us.

-Candice Frederick

Usually when people think of Grease, flashbacks of Frankie Avalon serenading a pink-haired Didi Conn in the iconic “Beauty School Dropout” scene come to mind. Or John Travolta dancing on the hood of a Ford 1948 with his pals, belting out “Greased Lightning”. Or even Travolta and a leather-clad Olivia Newton-John’s epic final song and dance number, “We Go Together”. But many overlook the smaller yet significant portrayal of rebel leader Rizzo by Stockard Channing. In a performance that epitomized the girl power movement before it became a much talked about thing, Channing infused both sensitivity and toughness in a character that we loved to hate (or was it hate to love?).

When we first meet Rizzo, she’s sashaying onto the campus decked in skin-tight all-black attire with her two besties on the first day of school. With one quick summation of the scene, she deems it mildly worth her presence, and declares “We’re gonna rule the school.” Even just knowing her for all of a few minutes, we don’t have a doubt in our minds that she will. With just one look, Channing seduces audiences with an alluring combination of intimidation and curiosity. While she’s not what you’d call approachable, there’s something about her assuredness and femme fatale-ness that makes you yearn for the camera to stay on her. Channing makes sure that Rizzo isn’t just the naughty head bitch of the crew; the nuance she brings is measured down to the last drop.

We later learn that while Rizzo has the attention of both gals and gents, she secretly faces the risk of an unplanned pregnancy. Though the movie doesn’t spend many scenes on this, it is Channing who creates a bold moment with an affective rendition of “There Are Worse Things I Can Do”. The song, which even by itself has an empowered message, is further punctuated by the confidence and directness of Channing’s lyrical middle figure response to the gossipers and naysayers who’d undoubtedly brand her. It was a poignant reaction that only Rizzo could convey, as embodied by the remarkable Channing.

Channing took what could have been seen as a typical “mean girl” role and turned Rizzo into an indelible character we can all look up to, one that was made up more than just snarls and pouty lip gloss. She made her one of us.

-Candice Frederick

JxSxPx's rating:

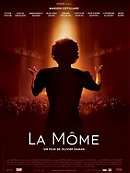

La Vie en Rose (2007)

Marion Cotillard

Today, she is perhaps best known as the existential femme fatale in such Christopher Nolan epics as The Dark Knight Rises, or Inception. But before she stepped out as Johnny Depp’s arm candy in Public Enemies, or glimmered as Adriana in Midnight in Paris. Marion Cotillard was a promising French actress hoping to break out of the mundane movie roles she was offered in her native country. For more than a decade, she was seen as a fresh face forever locked in certain cinematic stereotype. Then along came the biopic of trouble chanteuse Edith Piaf and, suddenly, Cotillard was the talk of the international film community. Winning nearly every award possible, including an Academy Award (unheard of for a foreign language performance), the actress suddenly skyrocketed to the top of many moviemaker’s A-lists.

In retrospect, it seems odd that Cotillard would win such acclaim for such a showy part. She didn’t sing any of Piaf’s classic torch songs herself (most were handled by singer Jil Aigrot) and bares only a passing resemblance to the miniature marvel. But just ask anyone aware of Piaf’s personality and passion, ask the numerous devotees who’ve memorized every line and gesture of her creative canon and see if they don’t believe that Cotillard captured her subject flawlessly. In fact, some have even suggested that she actually channeled the late songstress during her performance. There is a delicacy and a drive that cuts through the standard biography to make a bigger than life character decidedly down to Earth. There are also a lot of flaws and foibles on display, Cotillard making each and every one seem part of the bigger picture of Piaf’s unconventional life.

For anyone, playing a legend is hard enough. In Piaf’s case, she represents an entire generation of French cultural couture. From her earliest days in the streets of Paris to her untimely death at age 47, she represented a heritage rapidly disappearing behind the ravages of war and significant social change. Cotillard captured this moving mythology, the endemic, enduring symbolism of an entire nation’s acknowledged traditions. More than anything else, the actress found the central tragedy of the singer’s short life. Add in her addictions, her failed romances, and her powerful pint-sized pipes and you have Piaf as a true icon brought to reality by an artist with an equal frailty, and force. Singing is not just a song. It’s interpretation. The same can be said for what Marion Cotillard was asked to do here, and the results are stunning.

-BG

Today, she is perhaps best known as the existential femme fatale in such Christopher Nolan epics as The Dark Knight Rises, or Inception. But before she stepped out as Johnny Depp’s arm candy in Public Enemies, or glimmered as Adriana in Midnight in Paris. Marion Cotillard was a promising French actress hoping to break out of the mundane movie roles she was offered in her native country. For more than a decade, she was seen as a fresh face forever locked in certain cinematic stereotype. Then along came the biopic of trouble chanteuse Edith Piaf and, suddenly, Cotillard was the talk of the international film community. Winning nearly every award possible, including an Academy Award (unheard of for a foreign language performance), the actress suddenly skyrocketed to the top of many moviemaker’s A-lists.

In retrospect, it seems odd that Cotillard would win such acclaim for such a showy part. She didn’t sing any of Piaf’s classic torch songs herself (most were handled by singer Jil Aigrot) and bares only a passing resemblance to the miniature marvel. But just ask anyone aware of Piaf’s personality and passion, ask the numerous devotees who’ve memorized every line and gesture of her creative canon and see if they don’t believe that Cotillard captured her subject flawlessly. In fact, some have even suggested that she actually channeled the late songstress during her performance. There is a delicacy and a drive that cuts through the standard biography to make a bigger than life character decidedly down to Earth. There are also a lot of flaws and foibles on display, Cotillard making each and every one seem part of the bigger picture of Piaf’s unconventional life.

For anyone, playing a legend is hard enough. In Piaf’s case, she represents an entire generation of French cultural couture. From her earliest days in the streets of Paris to her untimely death at age 47, she represented a heritage rapidly disappearing behind the ravages of war and significant social change. Cotillard captured this moving mythology, the endemic, enduring symbolism of an entire nation’s acknowledged traditions. More than anything else, the actress found the central tragedy of the singer’s short life. Add in her addictions, her failed romances, and her powerful pint-sized pipes and you have Piaf as a true icon brought to reality by an artist with an equal frailty, and force. Singing is not just a song. It’s interpretation. The same can be said for what Marion Cotillard was asked to do here, and the results are stunning.

-BG

JxSxPx's rating:

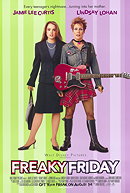

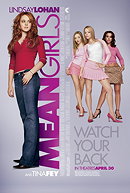

Freaky Friday (2003)

Jamie Lee Curtis

Body-switching comedies tend to be airy fluff, but they present a challenge to the lead performers that can elevate the material to a singularly masterful level. Mark Waters’ 2003 remake of the Disney family favorite Freaky Friday is certainly heavy on the fluff, but it’s also charismatically anchored by fantastic performances from its leads. Jamie Lee Curtis adopts the role that Barbara Harris memorably played the first time around, tackling the uptight mother-turned-rebellious-teen part with glowing gusto.

Adhering to formula rules, Waters gives Curtis and co-star Lindsay Lohan the first act to establish their actual characters before launching them into the swap. Curtis deftly communicates her busy, tired self who seems incapable of seeing eye to eye with her adolescent daughter. Then the bodies are switched and Curtis gets to shed her stuffy adulthood to reveal the playful youth inside.

What follows is a spunky, comically enhanced explosion of energy and a vibrant dissection of Lohan’s established teen character, now buzzing with a smug smarminess that looks great on Curtis. A new hairdo and wardrobe are mere extensions of her physical transformation, but the real change can be seen deep in Curtis’s body. She boils down all of that teenage angst to a delightfully funny series of gestures and shapes, slouching in chairs and pulling her legs up in the car so she can stick her feet on the dash.

These markers clearly connect her to the Lohan version of the character, but it’s how Curtis embodies them so honestly that makes her performance stand out as uniquely special. She manages to extract the delicious comic undertones and send them to the surface without simply parodying the character she has suddenly transformed into. It’s a wonderful challenge that she meets head on with great excitement, unleashing a colourful array of mannerisms that are both true to the character and refreshing to see in the hands of an adult performer. It helps that Curtis is so willing (and even eager) to poke fun at herself, especially when she laments how aged her adopted body is, lambasting her looks by comparing herself to the Crypt Keeper. I guess youth isn’t wasted on the young after all.

-Aaron Leggo

Body-switching comedies tend to be airy fluff, but they present a challenge to the lead performers that can elevate the material to a singularly masterful level. Mark Waters’ 2003 remake of the Disney family favorite Freaky Friday is certainly heavy on the fluff, but it’s also charismatically anchored by fantastic performances from its leads. Jamie Lee Curtis adopts the role that Barbara Harris memorably played the first time around, tackling the uptight mother-turned-rebellious-teen part with glowing gusto.

Adhering to formula rules, Waters gives Curtis and co-star Lindsay Lohan the first act to establish their actual characters before launching them into the swap. Curtis deftly communicates her busy, tired self who seems incapable of seeing eye to eye with her adolescent daughter. Then the bodies are switched and Curtis gets to shed her stuffy adulthood to reveal the playful youth inside.

What follows is a spunky, comically enhanced explosion of energy and a vibrant dissection of Lohan’s established teen character, now buzzing with a smug smarminess that looks great on Curtis. A new hairdo and wardrobe are mere extensions of her physical transformation, but the real change can be seen deep in Curtis’s body. She boils down all of that teenage angst to a delightfully funny series of gestures and shapes, slouching in chairs and pulling her legs up in the car so she can stick her feet on the dash.

These markers clearly connect her to the Lohan version of the character, but it’s how Curtis embodies them so honestly that makes her performance stand out as uniquely special. She manages to extract the delicious comic undertones and send them to the surface without simply parodying the character she has suddenly transformed into. It’s a wonderful challenge that she meets head on with great excitement, unleashing a colourful array of mannerisms that are both true to the character and refreshing to see in the hands of an adult performer. It helps that Curtis is so willing (and even eager) to poke fun at herself, especially when she laments how aged her adopted body is, lambasting her looks by comparing herself to the Crypt Keeper. I guess youth isn’t wasted on the young after all.

-Aaron Leggo

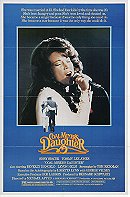

Coal Miner's Daughter (1980)

Beverly D'Angelo

Michael Apted’s wonderful Coal Miner’s Daughter is understandably most closely associated with Sissy Spacek’s brilliant performance as Loretta Lynn. But Beverly D’Angelo’s turn as Patsy Cline is as riveting on screen as Spacek’s. D’Angelo, like Spacek, chose to do all her own singing in the film. Taking on such an iconic voice as Cline’s is no easy feat, yet she makes it seem effortless. She sings beautifully and believably as Cline and shines whenever the camera is on her onstage. Her performance of “Sweet Dreams” is a highlight in a film filled with f musical moments, and it is to D’Angelo’s credit that she delivers the song with so much feeling and confidence.

Patsy Cline’s friendship with Loretta Lynn is really the second love story in the film (after Loretta and Doolittle (Tommy Lee Jones, also excellent). While it begins with Lynn in awe of one of her idols, it quickly grows into deeper friendship as they head out on tour together. While Lynn begins to deal with all that her newfound fame brings, Cline is a stable and supportive figure in her life. D’Angelo and Spacek portray a friendship between women that feels real and strong. They’re not petty or competitive, but instead convey affection for one another that makes their friendship feel authentic. D’Angelo is especially good at balancing Cline as mentor and friend, as she is always honest and plain-speaking, but also equally warm and funny.

D’Angelo’s portrayal of Patsy Cline is so good precisely because she makes her a three-dimensional person who never seems like a caricature of a real-life figure. Despite making her first appearance halfway through the film, D’Angelo makes an impression that lasts far beyond her death in a tragic plane accident—an accident that would go on to affect Lynn greatly. Had D’Angelo been less convincing or committed to her role, the fallout from her death would have felt cheap and undeserved, but instead it’s one of the most affecting moments in the film. Patsy Cline in Coal Miner’s Daughter will always remain a high point in D’Angelo’s career for many reasons, not the least of which include her wonderful chemistry with Spacek, her terrific musical performances, and the energy and warmth with which she imbued the role.

-JM Suarez

Michael Apted’s wonderful Coal Miner’s Daughter is understandably most closely associated with Sissy Spacek’s brilliant performance as Loretta Lynn. But Beverly D’Angelo’s turn as Patsy Cline is as riveting on screen as Spacek’s. D’Angelo, like Spacek, chose to do all her own singing in the film. Taking on such an iconic voice as Cline’s is no easy feat, yet she makes it seem effortless. She sings beautifully and believably as Cline and shines whenever the camera is on her onstage. Her performance of “Sweet Dreams” is a highlight in a film filled with f musical moments, and it is to D’Angelo’s credit that she delivers the song with so much feeling and confidence.

Patsy Cline’s friendship with Loretta Lynn is really the second love story in the film (after Loretta and Doolittle (Tommy Lee Jones, also excellent). While it begins with Lynn in awe of one of her idols, it quickly grows into deeper friendship as they head out on tour together. While Lynn begins to deal with all that her newfound fame brings, Cline is a stable and supportive figure in her life. D’Angelo and Spacek portray a friendship between women that feels real and strong. They’re not petty or competitive, but instead convey affection for one another that makes their friendship feel authentic. D’Angelo is especially good at balancing Cline as mentor and friend, as she is always honest and plain-speaking, but also equally warm and funny.

D’Angelo’s portrayal of Patsy Cline is so good precisely because she makes her a three-dimensional person who never seems like a caricature of a real-life figure. Despite making her first appearance halfway through the film, D’Angelo makes an impression that lasts far beyond her death in a tragic plane accident—an accident that would go on to affect Lynn greatly. Had D’Angelo been less convincing or committed to her role, the fallout from her death would have felt cheap and undeserved, but instead it’s one of the most affecting moments in the film. Patsy Cline in Coal Miner’s Daughter will always remain a high point in D’Angelo’s career for many reasons, not the least of which include her wonderful chemistry with Spacek, her terrific musical performances, and the energy and warmth with which she imbued the role.

-JM Suarez

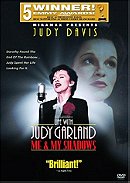

Judy Davis

Countless actors have received accolades for portraying real people. Few, however, become the person they play, at least not as wholly as Judy Davis did when she undertook the difficult assignment of playing Judy Garland in Life with Judy Garland: Me and My Shadows. Davis’ transformation is so complete that it has inspired a YouTube video showing Davis and Garland side by side performing the filming of “The Trolley Song” in Meet Me in St. Louis, and the two are virtually identical. Still, it isn’t Davis’ ability to capture Garland’s fidgety mannerisms and manner of speaking, it’s her ability to capture Garland’s attitude, inflecting meaning in the most minuscule phrase, giving punch to minor words or phrases just as Garland would, both when Garland was in character and out. Garland’s life was one of Hollywood’s most complex, making her one it’s most tortured souls and lifelong drug addict, and Davis shows us the angst and pain behind every magical film moment Garland gave us. In no scene is Davis’ power more evident than when Garland calls John F. Kennedy at the White House to convince CBS execs that there was an audience for her TV variety show; tough, vulnerable, scared, coy, and sexy—she is all that in a matter of minutes.

Davis plays Garland from her early 20s until her death (the teen Garland is played by Tammy Blanchard in another exceptional performance). So many film biopics follow a predictable pattern—the rise to fame, the fall from grace, and the eventual redemption. However, in Garland’s case, this was a repeating pattern; an Oscar nominee one year, then a few years later sneaking out of hotels wearing all of her clothes to avoid paying the bill. Davis’ performance is a bifurcated one, therefore, showing us Judy on top and Judy in the depths of addiction, the happy bride and new mother and the dejected lover who can barely get out of bed, an internationally loved superstar and washed up yesterday’s news. No matter where Garland was in her life, high or low, Davis captures the complexity of her personality and life, making us empathize and helping us to understand how the studio system of the ‘30s created a psychological nightmare for one its greatest stars.

-MA

Countless actors have received accolades for portraying real people. Few, however, become the person they play, at least not as wholly as Judy Davis did when she undertook the difficult assignment of playing Judy Garland in Life with Judy Garland: Me and My Shadows. Davis’ transformation is so complete that it has inspired a YouTube video showing Davis and Garland side by side performing the filming of “The Trolley Song” in Meet Me in St. Louis, and the two are virtually identical. Still, it isn’t Davis’ ability to capture Garland’s fidgety mannerisms and manner of speaking, it’s her ability to capture Garland’s attitude, inflecting meaning in the most minuscule phrase, giving punch to minor words or phrases just as Garland would, both when Garland was in character and out. Garland’s life was one of Hollywood’s most complex, making her one it’s most tortured souls and lifelong drug addict, and Davis shows us the angst and pain behind every magical film moment Garland gave us. In no scene is Davis’ power more evident than when Garland calls John F. Kennedy at the White House to convince CBS execs that there was an audience for her TV variety show; tough, vulnerable, scared, coy, and sexy—she is all that in a matter of minutes.

Davis plays Garland from her early 20s until her death (the teen Garland is played by Tammy Blanchard in another exceptional performance). So many film biopics follow a predictable pattern—the rise to fame, the fall from grace, and the eventual redemption. However, in Garland’s case, this was a repeating pattern; an Oscar nominee one year, then a few years later sneaking out of hotels wearing all of her clothes to avoid paying the bill. Davis’ performance is a bifurcated one, therefore, showing us Judy on top and Judy in the depths of addiction, the happy bride and new mother and the dejected lover who can barely get out of bed, an internationally loved superstar and washed up yesterday’s news. No matter where Garland was in her life, high or low, Davis captures the complexity of her personality and life, making us empathize and helping us to understand how the studio system of the ‘30s created a psychological nightmare for one its greatest stars.

-MA

JxSxPx's rating:

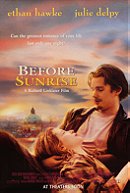

Julie Delphy and Ethan Hawke

I wonder if by the year’s end, the final installment of “The Celine and Jesse Trilogy” aka Before Midnight, will find itself in the Golden Globes’ Musical or Comedy category, and clean up there? Each film in the series is effortlessly romantic, there is an extremely memorable song in one (“A Waltz for a Night” which is referenced as a major plot point in the latest), and despite being intellectual and at times bracingly dramatic, they happen to also be extremely funny films in their own magical and real way. The emotional honesty shared by a long-tethered couple can be awkwardly funny, a code written between two people that very few others can understand. Those vulnerable, intimate, and often embarrassing moments can be utterly hilarious, even, when in Before Midnight, our couple’s journey happens in between a cavalcade of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?-esque damning insults and barbed taunts. These sunny, spontaneous moments that are expertly-placed throughout each of the films give everyone a relief; a moment to take a breath.

To me there is no greater joy than watching actors get to create characters in a cinematic space beyond the traditional 90 minutes to two hours; to watch them grow, to watch their characters grow with them in surprising directions. It is a rare and beautiful gift that an actor would get to record their characters’ progress over the course of nearly 20 years, as Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke do in Richard Linklater’s modern romantic comedy classics with Celine and Jesse. Delpy runs such an astounding gamut, brittle, sensual, electric. Hawke matches her at each turn with cockiness, passion, boyish guile and an infuriating intellectual superiority pose that makes you want to crack him one in the jaw. The two actors savor each moment opposite one another, then, fearlessly, intellectually they devour one another and deconstruct what it means to be a couple and how hard that is. Theirs is a lusty relationship, and each film is another long, hot summer with Celine and Jesse, the mercurial couple you’ve either known or been half of at some point.

The actors bring exuberance, a clear command of their characters, and a deeply-felt commitment to emotional truth hardly ever seen in typical modern romantic comedies. Yet in the end, it is the romance that lingers in the viewer’s mind, and keeps everyone coming back to see if they will stay together despite what feels like nothing but a series of insurmountably riskier odds against their union staying strong. Meticulously directed and written by Richard Linklater, and beautifully acted by Delpy and Hawke, Celine and Jesse have officially achieved iconic film character status in 1995, and nearly 20 years later, in a just world, they will both be recognized with a long line of acting awards and nominations come the end of the year; not just the writing award that they should most deservedly win.

-MM

I wonder if by the year’s end, the final installment of “The Celine and Jesse Trilogy” aka Before Midnight, will find itself in the Golden Globes’ Musical or Comedy category, and clean up there? Each film in the series is effortlessly romantic, there is an extremely memorable song in one (“A Waltz for a Night” which is referenced as a major plot point in the latest), and despite being intellectual and at times bracingly dramatic, they happen to also be extremely funny films in their own magical and real way. The emotional honesty shared by a long-tethered couple can be awkwardly funny, a code written between two people that very few others can understand. Those vulnerable, intimate, and often embarrassing moments can be utterly hilarious, even, when in Before Midnight, our couple’s journey happens in between a cavalcade of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?-esque damning insults and barbed taunts. These sunny, spontaneous moments that are expertly-placed throughout each of the films give everyone a relief; a moment to take a breath.

To me there is no greater joy than watching actors get to create characters in a cinematic space beyond the traditional 90 minutes to two hours; to watch them grow, to watch their characters grow with them in surprising directions. It is a rare and beautiful gift that an actor would get to record their characters’ progress over the course of nearly 20 years, as Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke do in Richard Linklater’s modern romantic comedy classics with Celine and Jesse. Delpy runs such an astounding gamut, brittle, sensual, electric. Hawke matches her at each turn with cockiness, passion, boyish guile and an infuriating intellectual superiority pose that makes you want to crack him one in the jaw. The two actors savor each moment opposite one another, then, fearlessly, intellectually they devour one another and deconstruct what it means to be a couple and how hard that is. Theirs is a lusty relationship, and each film is another long, hot summer with Celine and Jesse, the mercurial couple you’ve either known or been half of at some point.

The actors bring exuberance, a clear command of their characters, and a deeply-felt commitment to emotional truth hardly ever seen in typical modern romantic comedies. Yet in the end, it is the romance that lingers in the viewer’s mind, and keeps everyone coming back to see if they will stay together despite what feels like nothing but a series of insurmountably riskier odds against their union staying strong. Meticulously directed and written by Richard Linklater, and beautifully acted by Delpy and Hawke, Celine and Jesse have officially achieved iconic film character status in 1995, and nearly 20 years later, in a just world, they will both be recognized with a long line of acting awards and nominations come the end of the year; not just the writing award that they should most deservedly win.

-MM

JxSxPx's rating:

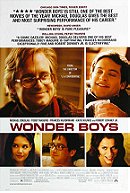

Wonder Boys (2000)

Michael Douglas

When Wonder Boys didn’t perform well in the opening weekend of its initial theatrical release, many wondered if blame could be attributed to Michael Douglas’ appearance in its promotional materials. The image being used at cinemas and in print publications nationwide was a close-up of a smirking Douglas in character as Grady Tripp, an increasingly crotchety, once-successful novelist, now middle-aged creative writing professor whose life spirals out of control on a hijinks—and crime—filled snowy night in Pittsburgh: Douglas’ hair was graying, his glasses were big, his face stubbly—not exactly what came to mind when mainstream America pictured famously suave leading man. Since the film boasted a supporting cast that included Frances McDormand, Tobey Maguire, Katie Holmes, and Robert Downey Jr. and was so critically well received, Paramount decided to re-release the film a few months later with new TV spots and ad campaign featuring more appealing, lively, and airbrushed shots its cast, Douglas included (there aren’t many conventionally “happy” moments in the film, so clever editing was employed).

Though the studio’s attempts at finding Curtis Hanson’s film a much deserved larger audience were noble by industry standards, the narrative of that original image of Douglas—and the real-life context of a famously gallant major Hollywood player embracing a make-under in a business where youth and sex appeal are so prized—fittingly mirrors Grady Tripp and the evolution of a character paralyzed by his inability to recreate the success of his youth against the demands of a big New York City publishing house impatiently awaiting his next (overly long but incomplete, we soon learn) manuscript they hope to make his new bestseller. It should be noted that Douglas isn’t especially funny in this role; rather, his tranquil (read: stoned, very stoned) attempts at handling his various entanglements with his lover (an underused McDormand), who happens to the be college president’s wife, his lecherous, pansexual book editor (a brilliant turn by Downey), and a pathologically lying, dog-killing, Marilyn Monroe memorabilia-stealing outcast student (a necessarily irritating Maguire) in need of his help, provide the space for Grady to evolve and mature as the hole he’s digging for himself grows deeper and deeper.

Grady makes a lot of bad decisions—and sometimes, even worse, no decisions at all—that require a leap of screenwriting faith at times (the film was adapted from the quirky bestseller by Michael Chabon), but under Hanson’s direction, Douglas proceeds with quiet assurance and conviction that translates to Grady, allowing us to believe our eyes and ears even when we should all—Grady included—know better. Wonder Boys is truly a little seen gem, one that deserved far more of a hurrah than it received, even with two wide theatrical releases, but more importantly, it is Douglas’ most understated work and a bold change of pace from a career that threatened to be swallowed up by a rotation of slick suspense thrillers of varying quality, films that never challenged Douglas to step outside of what audiences expected to see from him. Douglas disappears into his performance as Grady Tripp, amazingly without the aid of prosthetics or a heavy-handed accent (though, years later, he’d make perfect use of both as Liberace in Behind the Candelabra, but we’ll save that for another list).

-Joe Vallese

When Wonder Boys didn’t perform well in the opening weekend of its initial theatrical release, many wondered if blame could be attributed to Michael Douglas’ appearance in its promotional materials. The image being used at cinemas and in print publications nationwide was a close-up of a smirking Douglas in character as Grady Tripp, an increasingly crotchety, once-successful novelist, now middle-aged creative writing professor whose life spirals out of control on a hijinks—and crime—filled snowy night in Pittsburgh: Douglas’ hair was graying, his glasses were big, his face stubbly—not exactly what came to mind when mainstream America pictured famously suave leading man. Since the film boasted a supporting cast that included Frances McDormand, Tobey Maguire, Katie Holmes, and Robert Downey Jr. and was so critically well received, Paramount decided to re-release the film a few months later with new TV spots and ad campaign featuring more appealing, lively, and airbrushed shots its cast, Douglas included (there aren’t many conventionally “happy” moments in the film, so clever editing was employed).

Though the studio’s attempts at finding Curtis Hanson’s film a much deserved larger audience were noble by industry standards, the narrative of that original image of Douglas—and the real-life context of a famously gallant major Hollywood player embracing a make-under in a business where youth and sex appeal are so prized—fittingly mirrors Grady Tripp and the evolution of a character paralyzed by his inability to recreate the success of his youth against the demands of a big New York City publishing house impatiently awaiting his next (overly long but incomplete, we soon learn) manuscript they hope to make his new bestseller. It should be noted that Douglas isn’t especially funny in this role; rather, his tranquil (read: stoned, very stoned) attempts at handling his various entanglements with his lover (an underused McDormand), who happens to the be college president’s wife, his lecherous, pansexual book editor (a brilliant turn by Downey), and a pathologically lying, dog-killing, Marilyn Monroe memorabilia-stealing outcast student (a necessarily irritating Maguire) in need of his help, provide the space for Grady to evolve and mature as the hole he’s digging for himself grows deeper and deeper.

Grady makes a lot of bad decisions—and sometimes, even worse, no decisions at all—that require a leap of screenwriting faith at times (the film was adapted from the quirky bestseller by Michael Chabon), but under Hanson’s direction, Douglas proceeds with quiet assurance and conviction that translates to Grady, allowing us to believe our eyes and ears even when we should all—Grady included—know better. Wonder Boys is truly a little seen gem, one that deserved far more of a hurrah than it received, even with two wide theatrical releases, but more importantly, it is Douglas’ most understated work and a bold change of pace from a career that threatened to be swallowed up by a rotation of slick suspense thrillers of varying quality, films that never challenged Douglas to step outside of what audiences expected to see from him. Douglas disappears into his performance as Grady Tripp, amazingly without the aid of prosthetics or a heavy-handed accent (though, years later, he’d make perfect use of both as Liberace in Behind the Candelabra, but we’ll save that for another list).

-Joe Vallese

JxSxPx's rating:

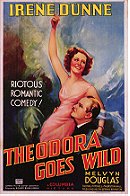

Theodora Goes Wild (1936)

Irene Dunne

If ever a star radiated warm-hearted decency, it was Irene Dunne. Her early career was built upon innate respectability and though her performances frequently included light operetta that showcased her vocal talent (well-served in chestnuts like Sweet Adeline, Stingaree and the 1935 version of Show Boat), her bread and butter was melodrama. These early 1930s women’s pictures–with titles like The Secret of Madame Blanche, No Other Woman and If I Were Free–are the foundation for her later, better-known performances in Magnificent Obsession, Penny Serenade and, most fondly remembered, the often-made and re-made weeper romance, Love Affair.

Her brilliance, however, persists mainly in several Cary Grant comedic pairings, My Favorite Wife and especially, The Awful Truth. The latter is a genuine cinematic gift and Dunne’s Academy Award-nominated performance ranks as a peerless execution of sophisticated wit bound with definitive timing and grace. As a sweetly duplicitous small town author in Theodora Goes Wild, made in 1936, just one year before Leo McCarey’s screwball classic, the intuitive comedic talents of Irene Dunne that culminated in The Awful Truth are first sharpened and realized on film.